HOW DOES a country produce such a man? The question arises every time we see a likeness of the 16th president. Early on there is the young man, intense, self-aware, posing for his formal photograph. He could be almost any would-be politician trying on his serious face for size. Yet even then, perhaps only because we have been granted the unwelcome gift of foreknowledge, there is something haunting about him, something driven, as if he never really had a youth but only a preparation.

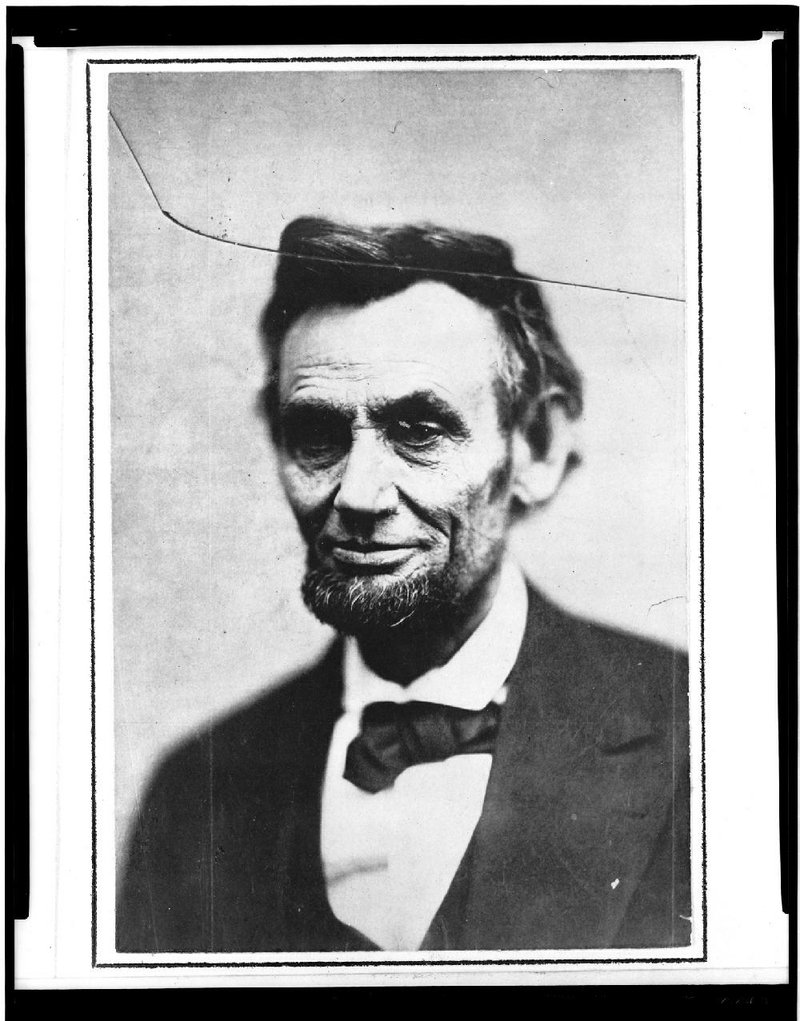

Then, in a photograph taken in February of 1865, toward the end of The War and his life, there is the familiar visage of Father Abraham in the broken-glass portrait that so faithfully mirrors the state of the Union at the time. It's an image that still crowds the throat with fear and wonder. And gratitude. Where did he come from?

The superficial answer is readily available: He came from Hardin County, Ky. He was born on Feb. 12, 1809--on the Big South fork of Nolin Creek a couple of miles outside Hodgenville in a log cabin with one door, one window and one clay chimney.

He came out of what was then the American West, aka the frontier. A family story had his cousin, Dennis Hanks, running down to the cabin on hearing the news to pick up the new, wrinkled, red-faced baby boy from beside an exhausted Nancy Hanks Lincoln. Whereupon little Abraham began squalling, and the disgusted Dennis handed him off to an aunt in attendance, saying only: "Take him! He'll never come to much."

Abe Lincoln always did have a way of fooling folks who jumped to conclusions about him. Fifty years after his birth, he would be nominated for the presidency of the United States by a still new party under less than auspicious circumstances, for the country he proposed to lead was about to come apart.

A reporter asked him to supply some information for a campaign biography. The candidate seemed amused by the question. "Why," he replied, "it is a great folly to attempt to make anything out of me or my early life. It can all be condensed into a single sentence; and that sentence you will find in Grey's Elegy--'The short and simple annals of the poor.' That's my life, and that's all you or anyone else can make out of it.''

We know his early life must have afforded a long, lanky farm boy a lot of time alone--time to read and time to just think things through. He would have gone to school maybe 12 months at most between his 8th and 15th birthdays. Yet somehow, this son of an illiterate father and loving but unlettered stepmother acquired an education. "Abe was not Energetic Except in one thing," his half-sister would later write, "he was active and persistent in learning--read Everything he Could."

Young Lincoln did have the King James Bible--who on the frontier didn't? You could tell as much from his House Divided speech that stirred the whole country during the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and by the biblical cadences, and content, of his Second Inaugural.

And he had Shakespeare. Stored away in his memory and at the ready. Shakespeare and the King James Bible. No one could say he entered the fray unarmed.

He had something else, too, something instinctive, visceral and deep: an abiding hatred and detestation of human slavery. He'd had the feeling ever since his experience as a young man floating a raft of cargo down the Mississippi to New Orleans, when he'd seen his first slaves. And it was only reinforced and refined by the wiles a politician gathers as he grows older. Where did that conviction come from?

Other Americans disliked slavery, too. Some even knew it was evil. But so many were willing to accept it as a necessary evil. And still others would have destroyed anything to get at it, including the American Union. But Abe Lincoln was no abolitionist in that sense. With him ending slavery was a moral necessity, but so was saving the United States of America. Somehow, against all odds and the conventional wisdom of his day, Mr. Lincoln accomplished both goals.

How did he do it, and why? The founding father he cited most often, Thomas Jefferson, had learned to live with slavery. Why couldn't Abe Lincoln just accept slavery and go on?

It's a mystery many an historian has explored by now, and many others surely will as long as there is a United States of America and a sense of justice in the world. Today let us put forth this theory--that Mr. Lincoln hadn't just felt but thought his way to freedom. He had come to believe that every man is entitled to the fruit of his own labor.

If he did not believe that a race of slaves was ready for full equality--did not the children of Israel have to spend 40 years in the wilderness before entering the promised land, and even then only to find freedom a constant struggle?--then this much he also knew, and said: The black man is equal to any other man in his right to enjoy the fruits of his own labor.

IF ABRAHAM Lincoln now belongs to the ages, as his friend said when closing his eyes for the last time, he was also a man of his age, complete with the ingrained mental habits of his time. For if he had not known them so well, from the inside, how could he have led others to see through them?

In perhaps his most controversial edict, the president would emancipate all the slaves in Southern territory--a move that is still guaranteed to rankle unreconstructed Confederates at every Civil War roundtable. He would be called a hypocrite for freeing the slaves only where he had no power to do so, and for not freeing them where he could. But his only legal justification for such a radical move was a narrow one: the wartime powers of the president. Which was why the Emancipation Proclamation emancipated only slaves in territory held by those at war with the United States of America at the time.

Legally, the proclamation changed nothing, not at first. Morally and politically, it changed everything. A thrill went through the country--and the world. This was no longer a war just to save the Union but a war to set men free. And as the Union troops advanced, so did freedom.

Even his old abolitionist critic, Frederick Douglass, who would eventually become his friend and admirer, recognized in hindsight that Mr. Lincoln's patience represented the better part of valor. As he would put it at a memorial ceremony for the Great Emancipator: "Had he put the abolition of slavery before the salvation of the Union," the decision would have been so unpopular, it would have "rendered resistance to the rebellion impossible. Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical and determined."

Abraham Lincoln knew he had to lead public opinion, that he could not force it. If he had tried, it would surely have turned against him and freedom itself. "With public sentiment," he once said, "nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed."

In the end, he would manage to win the most decisive battle of all, the one for public opinion. Which is another reason why this editorial of Feb. 12, 2016, is being written in a free country, specifically in Little Rock, Ark., U.S.A.--not C.S.A.

Editorial on 02/12/2016