Once upon a time, national political conventions could be as raucous as a mosh pit and as entertaining as a three-ring circus. They sometimes wound up being "brokered" behind the scenes by party bigwigs.

Republicans needed 10 ballots in 1920, when GOP potentates finally huddled during the night in a smoke-filled room (actually a suite) at Chicago's Blackstone Hotel to settle on Warren G. Harding. He was plucked from the pack, though he'd garnered just seven percent of first-ballot votes.

In the most flabbergasting instance, the 1924 Democratic conclave in New York took 16 days and 103 ballots to pick John W. Davis, back when party rules required a two-thirds vote to nominate. The ultra-marathon, waged by men in suits and ties sweating profusely in summer heat absent air conditioning, was the first political convention broadcast on radio.

In today's 24-hour cycle of perpetual reporting and punditry, cable-news channels would go berserk televising such spectacles. Wolf Blitzer and Megyn Kelly might explode on air with excitement.

Such high drama hasn't occurred for either party since 1952. But it's a plausible prospect for Republicans in 2016, as primary voting accelerates to warp speed Tuesday with contests in Arkansas and 10 other states. That's true even with Donald Trump's fast February start.

A brokered convention would be a nostalgia trip back to the radio era. As television began showing these quadrennial gatherings live to the nation after World War II, their prime purpose--nominating a presidential candidate--was ceasing to be a matter of any real doubt. What had been competitions turned into coronations.

While 10 of the two parties' 26 conventions from 1904 to 1952 required multiple ballots, none of the 30 since then has needed more than a single roll call. Most often, the perfunctory vote is unanimous or nearly so.

That has produced televised tedium, epitomized at the 1988 Democratic convention by Bill Clinton's soporific speech on behalf of Michael Dukakis, who had the nomination sewn up in

advance. The future 42nd U.S. president unfurled a 33-minute snoozer that seemed at least twice as long.

Ho-hum predictability took hold for both parties, to the degree that ABC, CBS and NBC have aired only digested highlights (such as they are) each evening the last few times around.

The main culprit in the demise of convention thrills and chills has been the spread of primaries and to a lesser extent caucuses--the methods now used to select delegates in just about every state, territory and the District of Columbia.

(That's right: The U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa and the Northern Marianas, as well as the commonwealth of Puerto Rico, get GOP delegates: 59 in total. Even though their residents have no vote in the Nov. 8 general election, they could conceivably decide a deadlocked nomination.)

Ubiquitous popular voting has ended the reigns of cigar-puffing party bosses in hush-hush huddles. Instead, the nominees are generally as predictable well before convention time as the serial ebb and flow of Mike Huckabee's waistline.

The former Arkansas governor has dropped out of this year's Republican race, along with assorted other wannabes--the latest departure being early book favorite Jeb Bush.

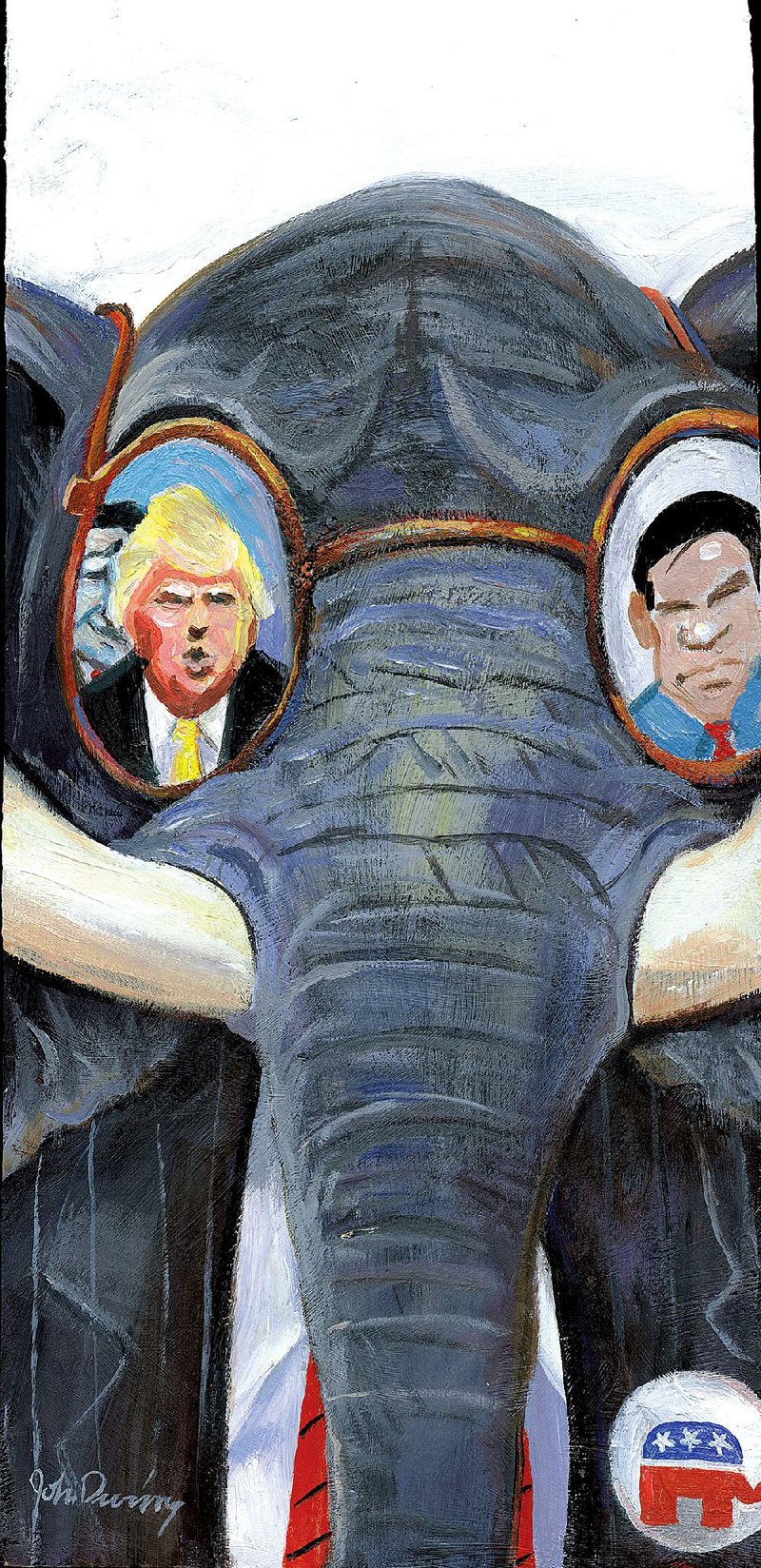

But five candidates are still in the fight: Trump, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, John Kasich and Ben Carson. Fevered contention over replacing deceased Supreme Court Justice Anthony Scalia is adding to the turmoil.

February's voting chose 133 delegates in four states: Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Nevada.

Those results have given Trump clear front-runner status. But his delegates so far total less than seven percent of what's needed for nomination. In his heralded South Carolina and Nevada wins, he still fell short of a voter majority, though his 46 percent in Nevada came close. The game is still in the first inning.

Now come this week's Super Tuesday contests in 11 states. Definitely the party campaign's biggest day, it will determine close to one-fourth of the GOP delegates: 595 out of 2,472. Another 155 will be selected in four states on Saturday. About 35 percent of total delegates will have been decided by the end of this week.

Like the great majority of 2016 contests, none of the week's 15 contests is a total winner-take-all event, so proportional distribution of delegates may continue.

That could well give the remaining candidates enough hope, whether justified or deluded, to carry on for at least a while--quite likely through March's mix of additional contests. By April Fool's Day, about two-thirds of delegates will have been chosen.

June 7 is the date of the party's last five primaries, including California's with 172 delegates, the most of any state. If the logjam continues after those last results are in, the grand old days of convention craziness could be revived when Republicans meet July 18-21 at Quicken Loans Arena in Cleveland.

In terms of America's political sanity, that's as likely to be for the worse as for the better. But it would be a bonanza for the ratings of TV's news channels--and delicious viewing during summer's doldrums (prior to the Aug. 5-21 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro).

"Brokered convention," the term for this audience-enticing drama, means that the chairman's gavel opens proceedings with the party's nominee still very much up in the air.

Nothing remotely like that has happened since 1976, when the Republicans convened with President Gerald Ford a nose ahead of challenger Ronald Reagan. Ford won on the first ballot, so it qualified as "contested" rather than flat-out "brokered."

Connoisseurs of American politics might point to the 1968 Democratic gathering in Chicago as a week of televised high drama.

But that mayhem took place primarily outside the convention hall as protesters and police battled in the streets. Despite impassioned delegate debate over Vietnam War policy, the nomination of Hubert Humphrey was never in serious doubt.

It has been 64 years since either major party's convention required more than a single vote. That happened in 1952, when the Democrats needed three ballots to choose Adlai E. Stevenson over Estes Kefauver and Richard Russell Jr.

For the Republicans, first-round victories have been standard since 1948. At that convention, Thomas Dewey won on the third ballot, topping Robert Taft and Harold Stassen. Like Stevenson, Dewey lost the general election.

A basic requirement for a multi-ballot convention is the persistence of at least three viable candidates to split the voting when the delegate roll call begins.

Democrat Harry Reid, the Senate minority leader, told CNN earlier this month that a brokered or contested convention "would be kind of fun" for his party.

But with only Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders still competing for the Democratic nomination, that's the longest of mathematical long shots. One or the other is sure to command a majority of the 4,763 delegates when the incumbent presidential party meets July 25-28 in Philadelphia.

Not so for the Republicans--assuming that Trump, Cruz and top mainstream contender Rubio continue to compete into July. It's more questionable whether Kasich and Carson can persevere to the finish.

After decades of pre-ordained nominees, rules for delegate selection have become complex enough that a brokered convention could have a dizzying outcome. A recent Washington Post headline referred to "the hopelessly, intentionally messy 2016 delegate process."

Every state has its own variations on basic party regulations. Here are the criteria for choosing Arkansas' 40 GOP delegates on Tuesday:

• Each of the Natural State's four congressional districts gets three convention delegates. A candidate winning a majority of a district's popular vote is awarded all three delegates. Otherwise, the leader collects two delegates, while the No. 2 finisher gains one.

• For the 25 at-large delegates, the rules become more circuitous. They are doled out proportionally, with each candidate garnering at least 15 percent of the statewide vote receiving at least one. But anyone winning a majority in the overall count gets all 25.

• All pledged delegates are required to vote for the candidate on their filing form during the first ballot, unless that candidate releases them or withdraws.

• Then there's a wild card: the state's three so-called Republican National Committee delegates, who automatically gain convention seats. They are the national committeeman, the national committeewoman and the chairman of the Arkansas Republican Party.

Each state and territory is entitled to three RNC delegates, party functionaries guaranteed a spot by their position. In a brokered convention, these 168 GOP "super delegate" stalwarts might wield the deciding votes--likely favoring a mainstream candidate over a renegade like Trump or Cruz.

Readers boggled by a process this byzantine can be pardoned for their confusion. The setup might give the decisive voice in second and later ballots, when the vast majority of delegates can change their vote, to non-elected party leaders--and/or those from territories with no presidential voice in November.

The track record of conventions since World War II makes a good case that some Republican candidate will eventually break from the pack and take a commanding lead before delegates head to Cleveland.

Instant analysis after Trump's resounding South Carolina triumph Feb. 20 suggested that he might be headed to victory that way.

Susan Page of USA Today called the real-estate mogul and reality-show host, making his first race for public office, "the unlikely front-runner now on a path to claim the Republican presidential nomination."

A cautionary note for Trump was raised in a Web posting by the Atlantic. The magazine pointed out two major unknown factors: "One is whether Trump has a ceiling of support. The second is whether even if he does, any of his remaining rivals can unify enough of the voters to beat him."

The answers to those questions--and the path to Cleveland--should be crystallizing by the end of March. But there is a distinctly better chance for a brokered GOP convention than at any time since smoke-filled hotel rooms fell victim to smoking bans.

That would leave party chieftains seeking some other hideaway, maybe a cigar bar, for their wheeling and dealing. Stay tuned.

Jack Schnedler, retired deputy managing editor/Features for The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, was elected by caucus in 1968 as a delegate pledged to insurgent Eugene McCarthy at Kentucky's Democratic State Convention.

Editorial on 02/28/2016