Dying from a wayward coconut is more likely than winning a Powerball jackpot, says a university professor -- yet people play anyway.

The urge to play the lottery game fascinates Philip Tew, an assistant professor of finance at Arkansas State University. He teaches students how people make decisions regarding money.

The lottery is one example of people putting the opportunity for short-term gain ahead of near-certain long-term benefit, he said.

Lottery players are far more likely to lose money than make money on the game. It doesn't matter if players pick numbers that have historically been drawn more often or buy tickets at stores that have produced winners in the past, Tew said.

"It's a random drawing," he said. "Some numbers may have been chosen more in the past, but overall, they're all going to have the same odds of being pulled."

The numbers -- five white and one red -- are drawn in the presence of multistate lottery draw officials, an independent auditor and a security official, according to the Multi-State Lottery Association, which operates Powerball. The lottery game is played in 44 states, including Arkansas; plus Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Draw equipment is kept in a locked, alarmed vault. The ball sets are sealed by independent auditors. All events are audio and video recorded when the vault is opened. The equipment is tested regularly, which includes X-rays and statistical tests for nonrandom behavior.

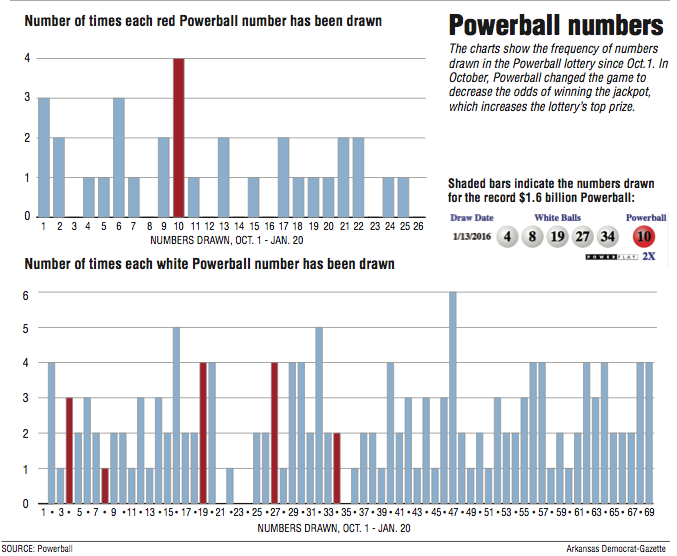

Pressurized air scrambles the 69 white balls and 26 red balls in separate globes before they float up through a clear cylinder.

The live drawings, on Wednesdays and Saturdays, are also open to the public. The whole process takes about two hours.

"Every time there's a drawing for the lottery, it's independent from the last time. You start all over," said Hassan Elsalloukh, an associate professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Department of Mathematics and Statistics. "The numbers chosen before have no impact on the future drawings."

Arkansas lottery officials said they couldn't comment on the Powerball's randomness. The Multi-State Lottery Association didn't return a request for comment.

Elsalloukh noted that the odds of winning the Powerball game decreased when more white numbers were added in October. The move effectively increased the likelihood of higher jackpots. When there is no winner in a drawing, money is added to the jackpot.

"You're not going to win," Elsalloukh said. "Basically, you have no chance."

Though players became less likely to win the jackpot, Arkansans flocked to buy lottery tickets earlier this month as the jackpot reached a historic level. Winners in California, Tennessee and Florida split the $1.6 billion jackpot. The numbers were drawn on Jan. 13. The odds of winning the top prize are one in 292 million.

Mega Millions, a competing multistate lottery, had what is now the second-largest lottery jackpot -- $656 million -- in 2012. The odds of winning Mega Millions are slightly better -- one in 259 million.

Precisely because lottery numbers are randomly drawn, there are more predictable ways to earn money on spare income, said Bob Williams, a senior vice president and managing director at Simmons First Investment Group.

Instead of buying four lottery tickets a week at a cost of $2 per ticket, a hypothetical lottery player could invest in the stock market over 30 years and likely earn thousands, he said.

Assuming a $32 per month investment and a 10 percent return rate, the player would amass $61,000 after 30 years -- plus keep the $11,500 investment. Just like the chances of winning the lottery, compounding investment income is predictable over long periods of time. From 1928 to 2015, the U.S. stock market has had an average return of 11.41 percent.

"The odds are clearly stronger in the financial markets than winning the lottery," Williams said. "The lottery reminds me of what someone said about making a small fortune -- start with a big one."

Nevertheless, both Williams and Tew stood in line to buy lottery tickets last week. Elsalloukh's wife bought him a ticket.

"The worst part about it was I bought it at the Kroger grocery store and one of my former students is an assistant manager and he was the one who sold them to me," Tew said. "He said, 'Dr. Tew, you were always telling us not to do this.' I said, 'Just give me the ticket.'"

Tew said if he were to win the Powerball jackpot -- which he stood about a .0000003425 percent chance of achieving -- he would take the annuity.

The three Jan. 13 Powerball winners have a choice. They can each take their one-third share of the lump-sum payout -- $930 million before taxes -- or receive their share of the full $1.6 billion in winnings in 30 payments over 29 years. Payments are guaranteed even if the winner dies.

Theoretically, Tew said, a winner could take the lump sum, invest it and surpass $1.6 billion through investments. But, he said, he wouldn't expect most lottery winners to be content to watch earnings grow slowly over time before withdrawing them.

"We're much more focused on the short term," he said. "We're always going to be driven to take action today."

Of course, all this talk about probability and logic has little to do with why people play the lottery, Elsalloukh said. As a form of entertainment, a $2 lottery ticket isn't so bad, he said.

"People believe in chance and obviously someone's going to win," he said. "So, mathematically speaking, the probability is almost zero, but it's not all about mathematics sometimes."

Metro on 01/23/2016