First in a series

- MAIN MENU

- PART I: 6 law firms top donations list

- PART II: Top donors net big wins

- PART III: Campaign money stirs debate over how judges picked

- State justices respond to donation questions

- After 2010 high court race, justice wed a top donor

- Firms file suits, donate together

- INTERACTIVE: Breakdown of campaign contributions to justice candidates

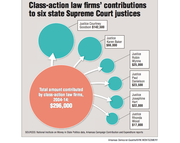

- GRAPHIC: Class-action contributions to justices

- How we did it

RELATED ARTICLES

http://www.arkansas…">How we did it http://www.arkansas…">After 2010 high court race, justice wed a top donor

High-profile class-action lawyer John Goodson, his Texarkana law firm and five law firms headquartered outside Arkansas rank among the biggest campaign donors to state Supreme Court justices, an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette analysis of public records shows.

The campaigns of Justices Courtney Goodson, Karen Baker, Robin Wynne, Paul Danielson, Josephine Hart and Rhonda Wood accepted an estimated $296,000 in total contributions from the law firms, most of it since 2009, the newspaper's review of campaign-finance disclosure records found.

Since 2004, 11 state Supreme Court candidates have reported receiving an estimated $452,000 from the law firms, which have worked together on class actions in Arkansas.

Campaign contributions to judges are a sensitive issue, as evidenced by American Bar Association recommendations on judicial ethics. That's especially true when the donor stands to benefit from a judge's court decision.

"Eighty-seven percent of the American public believe campaign contributions influence judges' decisions," said Mark Harrison, a national judicial ethics expert and Phoenix attorney.

Whether the donations "actually influence or not, the contributions arguably undermine the impartiality, or the appearance of impartiality, the public has a right to expect," he said. Harrison was chairman of the American Bar Association committee that wrote the group's suggested code of ethical conduct for all state court judges.

Arkansas Supreme Court justices have heard cases in which clients were represented by members of the class-action law firms that contributed to the justices' election campaigns.

Since mid-2008, state Supreme Court opinions have favored clients represented by John Goodson and his co-counsels in at least eight proceedings, which have translated into millions in legal fees, court records show.

A search of CourtConnect, the state's online court records system, didn't find any Supreme Court cases in that time that Goodson clients lost.

The Arkansas Supreme Court also sets rules and procedures for all state courts that are among the nation's most favorable to class-action plaintiffs' lawyers like Goodson and the other donor law firms, according to law journals and federal court documents.

In a 2010 Arkansas Bar Association magazine article, University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law professor Kenneth Gould said Rule 23 of the Arkansas Rules of Civil Procedure is "among the most favorable" of all states to class-action plaintiffs and their lawyers.

As interpreted by the Arkansas Supreme Court, Rule 23 also is more friendly to plaintiffs than are federal court class-action procedures, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville law professor John Watkins wrote in a different 2010 Arkansas Bar Association article.

The biggest chunk of donations from the six law firms -- $142,500 -- found its way to Justice Courtney Goodson's 2010 campaign, her campaign contribution reports show.

In late 2011, about 18 months after her election victory and a divorce, she married John Goodson. She is running for chief justice in 2016.

Court records show that Courtney Goodson disqualifies herself from hearing her husband's cases, as state law dictates.

She does decide other cases that help set and interpret Arkansas' class-action procedures.

Even without a clear link between class-action lawyers' campaign donations and the Arkansas Supreme Court's decisions, "you've created the impression that money is buying your court," said David Stewart, retired executive director of the Arkansas Judicial Discipline and Disability Commission.

"Unless you have a smoking gun, you don't know what kind of impact the money really does have," said Stewart, now a University of Arkansas at Fayetteville adjunct law professor. "But you still have the problem of the appearance, when the system is set up the way it is."

Justices interviewed by the Democrat-Gazette say there is no improper connection between the six law firms' campaign contributions and the justices' opinions in those firms' cases and the court's rules for class actions.

That's because, the justices say, they purposely avoid learning who their campaign donors are, as the state code of judicial conduct instructs.

"I do not know what attorneys from which law firms contributed to my campaigns," Baker said in a written response to the Democrat-Gazette's questions. She says she does not look at contribution reports.

Even if the justices remain uninformed, public records still raise questions when a judge accepts campaign money, then decides a case in favor of a contributor, judicial ethics experts say.

The money

Besides Courtney Goodson, five other justices sitting on Arkansas' highest court reported donations from a group of class-action law firms in amounts ranging from $66,000 (to Baker in 2010 and 2014) to $17,000 (to Wood in 2014), campaign-finance disclosure reports show.

The gifts represented about $1 in every $4 given to Courtney Goodson's, Baker's and Wynne's campaigns, about $1 in $10 to Hart's and Wood's, and $1 in $12 to Danielson's. The contributions date to 2006. The numbers don't include candidates' loans or gifts to their own campaigns.

Three of the class-action firms donated to the campaign of retired Justice Jim Gunter ($27,619), and two firms gave to retired Justice Donald Corbin ($3,000) and the late Chief Justice Jim Hannah ($17,250).

At least 80 individual lawyers, their spouses and other family members at the six law firms have been reported as donors to Supreme Court campaigns since 2004.

In any given race, the contributors supported the same candidate, and their contributions arrived at about the same time.

The gifts apparently are legal in Arkansas, a state ethics official says.

"There's no restriction against multiple employees from the same entity making the same contributions," said Graham Sloan, director of the Arkansas Ethics Commission. "That's provided they make it with their own money."

It is illegal to give someone money with the understanding that the recipient will -- under the recipient's name -- pass that money along to a candidate, Sloan said. Campaign contribution reports must list the name of the person who actually provides the money, he said.

Along with John Goodson's Keil & Goodson firm in Texarkana, the other law firms that have donated significantly to Arkansas Supreme Court justices are based in Texas, Oklahoma and Pennsylvania.

They are Nix Patterson & Roach of Daingerfield, Texas; Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check of suburban Philadelphia; Crowley Norman of Houston, Texas; Reggie Whitten and Michael Burrage of Oklahoma, affiliated with several firms over the past dozen years; and attorney Jason Roselius of Oklahoma, also with multiple law firms, according to case records.

All have worked with Keil & Goodson on class-action lawsuits in Arkansas, court records show.

Usually, the cases involve a client or clients who seek to represent a group of consumers -- called a "class." Their lawsuits claim that companies have misrepresented products or shortchanged customers. Among the favorite targets are auto and property insurance companies.

Representatives for the law firms did not reply to the newspaper's questions and requests for interviews.

Class-action victories

Keil & Goodson and various co-counsels from the five out-of-state firms have been involved in at least 17 class-action appeals or related proceedings before the Arkansas Supreme Court between 2006 and 2014, the state's online court records show.

Before early 2008, the firms won three high-court proceedings and lost three, the newspaper's review found. Two more ended when the Supreme Court approved joint motions from both sides to dismiss or stay proceedings, online court records show.

Since mid-2008, the Keil & Goodson firm and its out-of-state co-counsels have been involved in at least nine proceedings and have won eight, according to Supreme Court case records.

Millions of dollars in attorneys' fees have ridden, and still ride, on those high-court decisions, court records show.

It's difficult to know exactly how much the Arkansas Supreme Court's favorable opinions were worth in legal fees to the class-action lawyers. One appeals court decision can affect several similar class actions in ways that aren't readily visible in court records. And many Arkansas circuit court case documents aren't available online.

Even so, one significant win before the Arkansas Supreme Court for Keil & Goodson and class-action co-counsels came in 2008 when the court unanimously denied several requests for writs, or actions, from to the United Services Automobile Association (USAA).

The proceeding, United Services Automobile Association v. Miller Circuit (SCT. 08-935), came out of class actions filed in state courts around the country alleging that insurers used computer software, including one named "Colossus," to improperly reduce payments for bodily injury claims.

In the Arkansas Supreme Court appeal, the insurance company sought to overturn decisions from Miller County Circuit Court, where the case was filed. The Arkansas high court denied the requests and sent the insurers back to the Miller County court for further proceedings.

A year later, the United Services Automobile Association companies settled in the Texarkana courthouse in a case titled Soto v. USAA (CV-09-132-3).

Among the terms, the insurers agreed to pay plaintiff attorneys' fees of $8 million, court records show.

The law firms representing the plaintiffs included three of the six big donors to Arkansas Supreme Court candidates: Keil & Goodson, Nix Patterson & Roach, and attorney Jason Roselius' firm then, Nelson, Roselius, Terry, O'Hara & Morton.

Since the Supreme Court's 2008 denial of United Services Automobile Association's appeal, dozens of other insurers have settled "Colossus" suits, and plaintiffs' attorneys have reaped tens of millions of dollars in fees, according to a number of insurance and trial lawyer websites as well as U.S. Supreme Court records.

A more recent Arkansas Supreme Court win that translated into big dollars for several of the class-action law firms was in November 2013. That case was Adams v. Cameron Mutual Insurance (CV-13-456).

The class action started in Miller County Circuit Court and moved to federal court. The U.S. district court then asked the Arkansas Supreme Court to rule on a question of state law. The question concerned a type of homeowner's policy called "actual cash value."

Crowley Norman and The [Jason] Roselius Law Firm worked on that federal case, which alleged Cameron Mutual Insurance underpaid claims on certain "actual cash value" policies because it wrongly depreciated labor costs.

The case was one of about 20 similar class actions filed over the same issue in courts in Arkansas. Two other big donor law firms are connected with those cases: Keil & Goodson and Kessler Topaz.

On Nov. 21, 2013, six Arkansas Supreme Court justices unanimously decided in Adams v. Cameron Mutual that state law bans insurance companies from depreciating labor costs in "actual cash value" claims -- if the policy doesn't define the term "actual cash value."

Courtney Goodson recused.

Since that ruling, at least three related class-action settlement agreements have followed.

Settlements last year for Adams v. Cameron (2:12-CV-2173) in U.S. District Court in Fort Smith and Cherry v. Shelter Mutual in Miller County Circuit Court included a combined $1.4 million in legal fees, court records show.

Just before year's end, a Polk County circuit judge also approved a settlement over the "actual cash value" issue in Adams v. USAA on Dec. 16. Keil & Goodson and other firms were awarded $1.85 million in legal fees and expenses.

'Avoid knowing'

Three current Arkansas Supreme Court justices who responded to questions from the Democrat-Gazette said their decisions are not influenced by campaign contributions.

Baker, Danielson and Wood say they follow an Arkansas Code of Judicial Conduct provision that says judicial candidates "should, as much as possible, not be aware of those who have contributed to the campaign."

A campaign spokesman for Wynne said the same. Hart did not respond to calls and emails.

In an email, Baker said that "even if I looked at the contribution reports, which I have not done, I would not necessarily know the law firms for which individual contributors worked."

Wood wrote: "Our rules require us to screen off any contributions to avoid knowing who contributes."

But national and state experts say voters find that hard to believe.

Judicial candidates usually attend their own fundraisers. And they're often acquainted with elected officials, lawyers, big business owners and others who contribute to political campaigns.

"Because public confidence is such an important factor in when judges should be stepping aside from cases, there is reasonable skepticism about how insulated judges really are from their donors," said Alicia Bannon, a senior counsel at New York University's Brennan Center for Justice.

"Especially when the dollar amounts are very high."

The American Bar Association recommends that state courts set a specific dollar or percentage limit for individual campaign donations and require judges who accept more to disqualify from hearing the donor's case.

In California, a judge must disclose contributions of $100 or more from parties in cases before him. An appeals court judge in that state is disqualified from hearing a case if anyone has donated more than $5,000 to him in the previous six years, according to that state's code of judicial ethics.

In Utah, a judge must recuse from a case if he accepted more than $50 in the previous three years from any party involved, according to that state's code of judicial conduct.

Few other state Supreme Courts, including Arkansas', have set specific donation limits that disqualify judges from hearing certain cases, said the American Bar Association's Harrison.

"Why do you think courts would resist?" Harrison asked. "I think they don't want to be limited to what a particular contributor can give."

Arkansas justices may cover their eyes to campaign donors' identities, but another provision of the state's Code of Judicial Conduct requires judges to remove themselves from cases where their "impartiality might reasonably be questioned."

A duty to avoid campaign donation information and a duty to recuse where an appearance of bias exists "seem like they're in conflict," said Billy Corriher, who studies judicial ethics in all 50 states for the Center for American Progress, a nonpartisan policy institute in Washington, D.C.

Those provisions make the Arkansas Code of Conduct appear "confusing and contradictory," Corriher said.

Justice Courtney Goodson disqualifies herself from cases involving her husband's law firm, as the state judicial ethics code requires for judges' close family members.

But she does weigh in on other class actions, according to case records. She has written or joined opinions that cite the Arkansas Rules of Civil Procedure regarding class actions, which experts say are friendly to class-action plaintiffs' lawyers such as Keil & Goodson.

The justice declined to answer the newspaper's questions about her decisions in class-action cases, the $142,500 in campaign gifts from all six class-action law firms and any issues that arise from her husband's reputation as one of the state's most successful class-action lawyers.

A spokesman for Goodson did provide a two-sentence statement: "I believe that judges should be accountable to the voters and that the Supreme Court belongs to the people. That's why, as a justice, I take extraordinary measures to ensure that the extensive rules and guidelines established by the court and the committee on judicial ethics are closely followed."

'A fair shake'

Ethics experts have long known about difficulties that can arise when lawyers contribute to judicial campaigns. Yet lawyers often make up the bulk of those donors.

The American Bar Association's model ethics rules recommend that a judicial candidate "instruct his or her campaign committee to be especially cautious" about contributions from "lawyers and others who might appear before a successful candidate for judicial office."

Arkansas' judicial conduct code doesn't contain that rule.

Two fundraisers who worked on state Supreme Court campaigns said they, like their candidates, didn't take note of donors.

Sherwood marketing consultant Linda Napper managed high court campaigns for Danielson, 2004 through 2008, and Wynne in 2014.

"We were so happy to get contributions. I never thought about the fact that some of these firms did class actions," she said.

Asked if she remembered Feb. 28, 2014, when the Wynne campaign reported $18,000 from three class-action law firm donors in a single day, Napper said she did not.

Most of the money, $14,000, came from firms headquartered in Texas and Pennsylvania. According to Wynne's campaign finance report, it was the campaign's second-biggest fundraising day. His campaign collected a total of just under $100,000.

Napper said she was too busy working to notice specific donations: "I work with lots of different campaigns. I file campaign finance reports with the majority of them."

Little Rock lawyer David H. Williams, who helped steer Raymond Abramson's unsuccessful 2012 Supreme Court campaign against winner Josephine Hart, said he didn't pay much attention to donors' names and contribution amounts. He believes his candidate didn't either.

Abramson's campaign reported $82,050 from five of the class-action firms. His was the second-largest recipient of those firms' donations in the past 12 years, behind Courtney Goodson, the newspaper's study found. (Abramson was elected to the Arkansas Court of Appeals, the state's second-highest court, in 2014.)

Asked why a group might give large sums to a Supreme Court campaign, Williams zeroed in on two possible reasons.

"One is they're giving money to a judge they believe has the type of philosophy they want to see in judges. That could be altruistic -- a fair judge who will give us a fair shake," Williams said.

"The other reason could be: they hope somebody tells the judge who gave the money."

Even if campaign managers don't keep an eye on big contributions from lawyers, donations by the Goodson team of class-action attorneys stand out because of their size and their delivery on about the same dates, the newspaper's review of campaign contribution reports found.

Lawyers and other staff members at Keil & Goodson and the five out-of-state law firms often contributed the then-maximum of $2,000 per candidate, per election, to Arkansas Supreme Court hopefuls, campaign contribution records show.

Those who gave less usually wrote checks of between $1,000 and $1,500. In the biggest-money races, the class-action lawyers' spouses, children or other family members also sent maximum and near-maximum checks.

Contributions from all other lawyers to Supreme Court candidates during the same 2004 to 2014 period were far smaller: an average of $317 per donation, records show.

And about 80 percent of the class-action law firms' contributions came from outside Arkansas, records show. Only about 6 percent of all other campaign contributions to Supreme Court candidates originated outside the state.

'Questions should be asked'

Arkansas Chief Justice Howard Brill has been a University of Arkansas at Fayetteville law professor for 40 years and is one of the state's best-known experts on judicial ethics. He was appointed in August to fill Hannah's unexpired term.

Since he has never run for public office, Brill is the only current Arkansas Supreme Court justice who hasn't reported campaign contributions from the class-action lawyer group, or anyone else.

Brill declined the newspaper's interview requests. But a 2011 article that he wrote for the Arkansas Law Review looked at campaign contributions and judges' responsibility to remove themselves from cases where influence might appear to exist.

One key issue Brill emphasized: the size of contributions by an individual or group matter.

"To illustrate, the maximum statutory contribution of $2,000 to the judicial campaign may not be viewed as significant," Brill wrote. "However, if the maximum amount is also given by the lawyer's spouse, the lawyer's children, and members of the lawyer's firm, further questions should be asked."

Brill's article also pointed to two then-recent Arkansas Supreme Court elections:

"The public campaign filings of newly elected Justices Courtney Henry [Goodson] and Karen Baker reveal that attorneys, firms, and Arkansas corporations contributed the maximum gifts allowed by law to the justices' campaigns. Attorneys were prominent supporters of their campaigns. In which instances are the justices required to recuse?"

MONDAY: Arkansas Supreme Court justices rule on class-action cases involving major campaign donors, cite ethics rule that exhorts them to avoid knowing who contributes to their election campaigns.

CASH AND THE COURT

Six law firms' total contributions to Arkansas Supreme Court races by candidate, 2004-14

Justice Courtney Goodson: $142,500 | [DETAILS]

Court of Appeals Judge Raymond Abramson: $82,050 | [DETAILS]

Justice Karen Baker: $66,000 | [DETAILS]

Former Justice Jim Gunter: $27,619 | [DETAILS]

Circuit Judge Tim Fox: $26,000 | [DETAILS]

Justice Robin Wynne: $25,000 | [DETAILS]

Justice Paul Danielson: $23,500 | [DETAILS]

Justice Josephine Hart: $22,000 | [DETAILS]

Former Chief Justice Jim Hannah: $17,250 | [DETAILS]

Justice Rhonda Wood: $17,000 | [DETAILS]

Former Justice Donald Corbin: $3,000 | [DETAILS]

SundayMonday on 01/24/2016