Arkansas has acquired a new supply of a drug needed to execute death-row inmates, according to an announcement Tuesday.

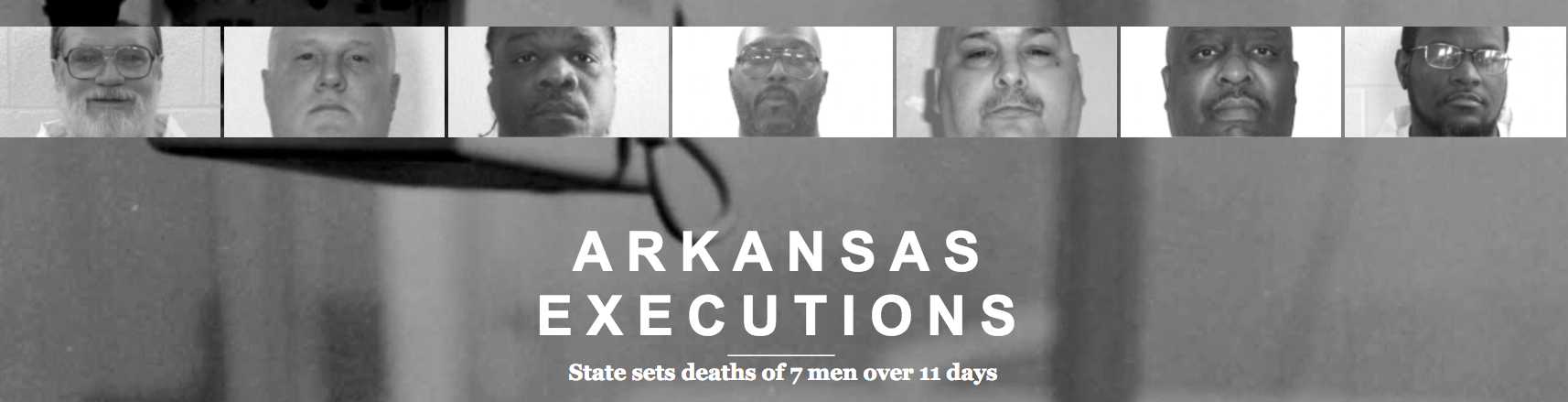

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

Executions in the state -- the last one 11 years ago -- are still on hold until judicial and administrative matters are resolved, however.

On Tuesday, a spokesman for the Arkansas Department of Correction announced that the agency had obtained a new supply of vecuronium bromide -- one of the three drugs used in state executions -- to replace a batch that expired at the end of June. Months ago, prison officials expressed pessimism that the state would be able to acquire more of the drug.

The prison spokesman, Solomon Graves, said the new supply of vecuronium bromide, a paralytic drug, has an expiration date of March 1, 2018. Graves declined to say how much was obtained but said there was enough for eight of the nine death row inmates who are fighting the execution law in court.

The state's supply of the other drugs for the three-drug cocktail, midazolam and potassium chloride, expire April 2017 and J̶u̶n̶e̶ ̶2̶0̶1̶7̶ January 2017*, respectively.

Although the drugs are on hand, prison officials cannot begin carrying out executions until the Arkansas Supreme Court issues a final order on the constitutionality of the state's lethal injection law.

On June 23, the high court ruled 4-3 that the law was constitutional, but for that ruling can go into effect, justices must issue a mandate, or court order. Once that is issued, the attorney general can ask the governor to set execution dates.

The inmates' attorneys had no comment Tuesday about the new drug supply.

Jeff Rosenzweig and John Williams, the attorneys for the nine death row inmates who have challenged the law, petitioned the court for a rehearing last Thursday. Last year, Gov. Asa Hutchinson set execution dates for eight of the nine inmates.

If the court denies the inmates' rehearing request, the justices will have to decide whether to stay their mandate, pending an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The inmates' attorneys argue that there are several questions of federal law concerning the case. Among them are whether the Arkansas Supreme Court's interpretation of the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Glossip v. Gross requires challengers of the state's execution law to find their own execution-method alternatives.

Such an application of the Glossip ruling, the attorneys wrote, imposes a "high burden" on the prisoners and poses an important question to be resolved by the nation's highest court.

In their request for a rehearing, Rosenzweig and Williams argued that the state high court's June ruling included several legal errors and that the majority misread the state constitution as it related to the lawyers' arguments against the law.

Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge's spokesman, Judd Deere, said Tuesday night that state attorneys will respond to Rosenzweig and Williams' petition by the end of the week.

It is unknown how long the state's high court will take to consider the merits of the latest legal arguments, but court officials say that if justices refuse the request for a rehearing, the court's mandate will be issued the same day.

Once the mandate is issued, Deere said, Rutledge will notify Hutchinson that the eight inmates can be scheduled to die.

Because of a combination of legal challenges and difficulties in obtaining execution drugs, Arkansas hasn't killed an inmate since 2005.

To make it easier for prison officials to obtain a supply of the life-taking chemicals, state lawmakers passed Act 1096 of 2015. The law spells out the three-drug protocol and includes language that prevents public disclosure of the identities of drug suppliers to shield the suppliers from criticism.

In September, Hutchinson set execution dates for the eight inmates, and Rosenzweig asked a Pulaski County Circuit Court to stay those executions pending a ruling on a challenge to the new law.

Rosenzweig argued that the prohibition on disclosing the drug sources violated his clients' rights to due process and violated the state constitution's public-record requirements.

He also argued that midazolam -- which has been used in botched executions in other states -- posed the risk of an unconstitutional "cruel or unusual" punishment for his clients.

In December, Circuit Judge Wendell Griffen ruled that the nondisclosure components of the law were unconstitutional, but his decision was overturned by the Supreme Court on appeal by the state.

A Section on 07/13/2016

*CORRECTION: The state Department of Correction’s supply of potassium chloride, one of three drugs used in executions, is set to expire Jan. 1, 2017, according to a prison spokesman. This article misstated the expiration date of the state’s supply of potassium chloride.