NEW YORK -- It was just another day on the media circuit for Lecrae, a 36-year-old Atlanta rapper with a Grammy Award under his belt and a best-selling book to promote.

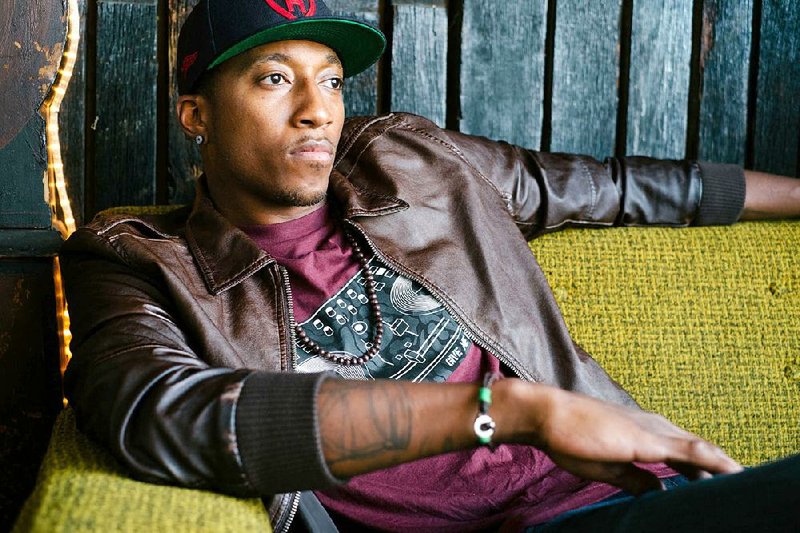

Dressed in the trendy chic of hip-hop celebrity -- flannel shirt-jacket, gold necklace over white T-shirt, expensive ripped jeans -- he rolled into a Financial District high-rise for an appearance on a syndicated radio show.

After a couple of minutes of chatter about his memoir -- a tale of surviving drugs, crime and sexual abuse -- the interview took a turn.

"Can I say what he said to the president of the United States?" asked host Eric Metaxas, a middle-aged white evangelical with a reputation as a conservative provocateur.

Metaxas was referring to the uproar triggered when black comedian Larry Wilmore referred to President Barack Obama using the n-word at the White House correspondents' dinner in April.

"Surely if he said that to the president of the United States, I can say it?" said Metaxas, oozing sarcasm, to the young black musician.

But the potentially fraught moment was instantly punctured.

"I'm pretty sure that's not a good idea," Lecrae said gently. The two men shared a chuckle, and the collegial conversation moved on -- just two traditional Christians sharing thoughts about the greatness of the Lord.

Forget how Lecrae looks, and how he sounds: The Metaxas show is exactly the kind of place where you'll find Lecrae, who has become one of the most successful Christian musicians alive today thanks largely to white evangelical fans.

In many ways, it's an easy fit. Evangelicals love to, well, evangelize, and in recent years they've grown tired of the mostly white cultural ghetto of Kirk Cameron movies and Christian praise bands they'd created over the past few decades. And for the born-again street kid, the clear, black-and-white truth of conservative Christianity was like a new drug he was happily hooked on.

Lately, though, the unlikely union has been hitting some bumps.

AN EVANGELICAL BEACON

As Lecrae's stature as a musician and cultural leader has risen, the 6-foot-4, smiley former drug dealer has become a lightning rod in the evangelical community. Some badly want him to speak out more about issues such as the racial unrest in Ferguson, Mo., and Donald Trump's rhetoric on immigration, while others say that he should "stick to the gospel."

Lecrae is part of a cohort that is itself in flux. The standoff between Trump and Hillary Clinton is challenging lots of narratives about American Christianity.

Is an evangelical someone who prioritizes fighting abortion and gay marriage or a pragmatist who looks for the middle ground? Does it go against Christian values to support a candidate who wants to deport Muslims and uses "Mexican" as a slur?

And is there an "evangelical" position on police treatment of blacks in 2016?

Cruising Manhattan in the back of a stretch black SUV on a recent afternoon, Lecrae Devaughn Moore knows that he represents a new evangelical archetype. And he loves it.

"What I bring is unique. No one else brings to the table what I am," he said. "That's how I look at myself -- a clear voice in the middle of it all."

American Christians, particularly the young, are dying for leaders willing to walk away from partisan polarization, and for some, Lecrae is a beacon. They flock to his concerts, they buy his books and they listen to his lectures.

"This generation doesn't have a Billy Graham," said LaDawn Johnson, a sociologist at Biola University, an evangelical school outside Los Angeles where Lecrae performed in April. "Lecrae is in a position where he could definitely -- for many young people -- be that voice and be that model."

'PASTOR-RAPPER'

Lecrae was raised in crime-ridden parts of Houston, Denver and San Diego where, he writes in his memoir, Unashamed, he tried to fill the hole left by his absentee father with drugs (using and selling), dreams of being a gang-banger, promiscuity and explosive fights. He showed an early interest in and talent for music and theater, and hip-hop rushed in to fill his void.

He yo-yoed back and forth between the violent thug life and the artistic crowd, the Christian and secular scenes, and very much between the white kids he met in high school and college and the black kids who had been his world before then.

After hitting his own rock bottom, he made his way to a college ministry focused on blacks at the University of North Texas, where he became a true believer. The 19-year-old was a zealous convert. Believing that he could no longer kiss girls -- even while acting in a play -- he quit theater. He dumped his beloved CD collection in a dumpster. He saw half the world as holy, or good, and half as secular, or evil.

This worldview plus great hip-hop was a winning combination. Christian camps and church youth programs began ordering CDs that he made at night, using borrowed equipment. He was asked to play at Christian conferences and megachurches. He was satisfying two thirsty music markets: Christians in the inner city, and Christians tired of mediocre music about faith.

In his book, he describes himself in that period as a "pastor-rapper." He saw his purpose as conversion.

In a 2008 song, "Go Hard," he raps about what he saw on mission trips to places where Christianity is unpopular:

"Went to Asia had to duck and hide for sharin' my faith

They tell me water it down when I get back to the States

They say tone the music down, you might sell a lot of records

But it's people out here dying and none of 'em heard the message."

But pretty soon the introspective rapper came up against perhaps the biggest modern-day evangelical issue: how to truly influence culture. His book cites well-known evangelical writer Andy Crouch, who criticizes the idea of a parallel, walled-off Christian culture with its own films and music. "'The only way to transform culture is to create culture,'" he quotes Crouch. And of himself: "It was time to leave the religious ghetto."

MAINSTREAM SUCCESS

Instead of preaching at people, Lecrae began to write about core spiritual issues such as poverty and materialism. The decision to get off his soapbox led to more mainstream listeners and success.

By 2011, he was invited to a Black Entertainment Television Hip Hop Awards event for up-and-coming rappers. In 2012, his mix tape Church Clothes was downloaded 100,000 times in the first 48 hours.

In 2014, his album Anomaly opened at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 overall. He has been nominated for Grammys five times, including for best rap performance in 2015. He has won two, in gospel and contemporary Christian categories.

In a 2014 lecture before a mostly white evangelical ministers conference, he said that Christians need to remain in the culture to change it and argued that church values are fading in America because Christians have become just a shell of "morality and religion and rules."

In his book he describes himself as wary now of rigid faith, of "a spiritual high that can lead to legalism."

Lecrae talks often and openly about his perspective on race and how it's in flux.

In the 2014 lecture, he described growing up in a "militant" household, with a mother who studied the Black Panthers and wanted him to embrace her understanding of what it means to be black.

"I had a feeling I didn't need you," he said as he bounded across the stage. "Then Jesus reached me." The sense of resentment toward white people, "it's not there anymore! Jesus changed me -- we're cool."

His concerts are packed with white evangelicals -- young people and soccer moms -- as well as black and Hispanic youth. He offers hip-hop without the obscenities, hip-hop about Jesus.

He wants to be that role model that Johnson described, particularly to his fellow evangelicals.

He has launched a media campaign called "Man-up" to encourage young urban men to embrace traditional roles as husbands and fathers. He travels to the Middle East and the Far East as a kind of celebrity conflict-reconciliation facilitator. He pens editorials on the need, post-Ferguson, post-Charleston, S.C., for more racial healing.

"He's an important voice. He has an immediate influence on churches when he speaks," said Southern Baptist leader Russell Moore.

SHADES OF GRAY

But as Lecrae gets bigger and more vocal, he gets more controversial. His decision to speak out about police brutality sparked a huge backlash on social media last summer (and also in recent weeks) -- mostly, he suspects, from white evangelicals. Many commentators said that he was wading into politics and should focus on "the gospel," he recalled during the New York tour.

A key turning point for him was Ferguson. It was perhaps the most forcefully he'd ever spoken out about the systematic disenfranchisement of black Americans. Then he spoke out about feeling that he was being shoved into a corner by the white evangelical community that has nurtured him.

"In order to cry out for my black brothers, I had to hate the police. It was like: 'Just stick to the gospel!' I was like, 'Wow, this is bigger than I thought,'" he says.

In recent months some in the Christian media say he's selling out, that he isn't "Christian enough." People dissect his comments, noting that he now refers to himself as "a rapper who happens to be Christian" rather than the other way around. News in mid-May that Columbia Records -- Sony Music's biggest label -- had signed him triggered social media panic about whether he could keep his faith at the same label as Beyonce and Snoop Dogg.

Meanwhile, some blacks believe he's using his massive stature too meekly.

Christena Cleveland, a professor of reconciliation at Duke University, said that Lecrae is a kind of "mascot" for white evangelicals -- someone who is let in but not to play a serious role.

"The same students who play Lecrae in their dorms are the same ones protesting Black Lives Matter," she said. "Somehow in their minds they're able to separate it."

It's not only blacks who want Lecrae to push it more.

Johnson, who is Hispanic, uses Lecrae in her classes. The week he performed at Biola, a swastika was found on campus, triggering a public discussion that Johnson thought was far too accepting of the symbol, concluding that it was just "joking around," she said. She wishes that Lecrae would lead the revolution among the mostly white evangelical elite to change such views.

"It would be nice if it could go to the next level," she said.

What would such a Lecrae revolution look like? As his SUV sped toward Midtown Manhattan, he ticked off his battle plan for healing America: "Unity, forgiveness, equity and justice."

"I don't see this as a black-white issue. In India, the Filipinos are being treated like they are less than human," he said. "I'm not focused on race, exactly. If blacks in America are treated equally, I'll move on to the next group."

Religion on 07/30/2016