Many Delta farmers and politicians are mounting an effort to dredge deeper channels in the White River, a waterway that has not been fully navigable by barges since a 2011 flood.

In February, agriculture shipping and export company Bunge North America closed the final three of its five ports along the river. And so, with no federal funds in place to pay for dredging, farmers have lost a transportation artery that has been vital since the 19th century, when the River and Harbors Act of 1892 originally authorized dredging of the river for barge traffic.

"That transportation artery over the years has amounted to millions of dollars of savings to the farm community along the White River Basin," said Harvey Joe Sanner, an Arkansas Waterways commissioner. "We're going to feel that hurt at a time that no one needs to feel any more hurt in this part of Arkansas."

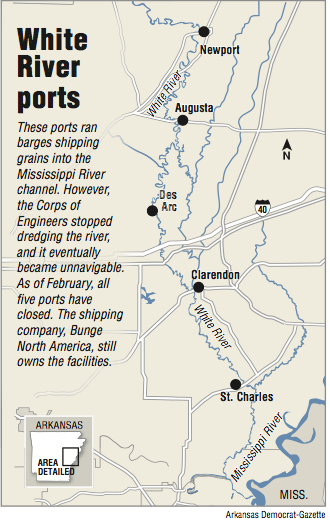

In years past, farmers would truck their harvests to the nearest of Bunge's ports, which are in Newport, Augusta, Des Arc, Clarendon and St. Charles.

But after 2011's flood left the White River with shallow sandbars and shoals, those ports turned to trucking to transport grains to market -- a significantly more expensive transportation method that passes costs on to farmers. Consequently, farmers were losing 25 cents to 30 cents a bushel, Sanner said.

For the coming harvest season, without the competitive edge provided by shipping on the river, many farmers likely will have to contract with trucking companies to haul their yields to facilities in West Memphis, Pine Bluff or North Little Rock.

Aside from the additional cost, the shift to trucking will increase tractor-trailer traffic: Each barge would carry the capacity of 60 truckloads, Sanner said. And during peak harvest season, the river would ferry four to six barges at any given time.

"This fall it's going to be a problem for farmers because we're not going to have any place to go with our crops," said former Arkansas Secretary of Agriculture Butch Calhoun, who leases 550 acres to rice and soybean growers near Des Arc. "It's hard on us."

Until 2011, the White River's channels had been regularly maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for more than 100 years, except for 10 between 1951 and 1961 because of a decline in traffic volume, according to Corps data. But the waterway had carried less than 1 billion ton-miles of cargo annually and had fallen into the "low-use" category.

"Maintenance of low-use inland waterways and harbors is not an administration budget priority," read a 2014 Corps report, and funding for regular maintenance of the channel dried up during recent budget cuts.

"Like most of eastern Arkansas, agriculture is our life," said Perry County Judge Mike Skarda. In his county, agriculture remains the largest employer and is the region's primary economic engine.

"The idea of having that transportation artery, which has been very, very valuable to the White River Basin, is still very much alive, and we're still trying to find ways to do it," Sanner said.

Sanner and area politicians have begun petitioning congressional representatives to provide funds through the Corps for dredging the 255 miles from Newport to the confluence of the Mississippi River. No price for the project has been estimated, but restoration of the channel becomes more costly as sediment accumulates, the Corps report said.

Meanwhile, not all in the region are so keen on the idea of dredging the river to accommodate barges.

In 1996, Congress gave preliminary approval to a project that would expand the river channel to a 9-foot-depth and 125-foot-width to accommodate larger barges. The project ran aground after a comprehensive study of the White River Basin discovered an array of potential environmental effects and drew criticisms from environmental groups. By 2000, funding dried up and the project was abandoned.

David Carruth, a lawyer in Clarendon, prefers the wild and unconstrained nature of the meandering river. He was a leading opponent of the abandoned dredging project, and he still opposes dredging.

"It's a foolish idea," Carruth said.

"When you hear people talk about these projects saving agriculture out there -- it's not. Agriculture gets saved by supply and demand, which has much more of an impact than being able to run a barge up and down the river," he said. "What you'd be doing is just subsidizing Bunge ... and you do it at the cost of hunting and fishing."

Carruth has noted how the wildlife and ecology of the region has benefited perceptibly in the years since dredging stopped. The marked increase of quality of habitat has given way to better fishing and hunting, he said. And protection over the site should be heavily emphasized because of the river basin's status as a Wetland of International Importance by UNESCO.

Even if dredging is funded and completed, however, the return of Bunge operations is not a certainty.

"We'd have to look at market conditions at the time. It's not just about Bunge. We'd have to have switching boats, operators, fleeting areas, and all sorts of other ancillary services that go along with the [grain] elevators," company spokesman Deb Seidel said. "Those would all have to be restored as well, and we do not own those," though the company still owns the closed ports.

Despite the obstacles standing in the way of resuming river shipping, "the dream is still there," Sanner said, "and we're still working toward it."

Metro on 07/31/2016