''The first mistake of Art is to assume that it's serious."

-- Lester Bangs, "James Taylor Marked for Death"

Everybody hates folk singers.

Or at least the stereotype -- the sincere guy with the acoustic guitar singing topical protest material or child ballads. The kind of folk singer Paul Simon used to be. The Coen Brothers even made a movie, 2013's Inside Llewyn Davis, just so they could time-travel back and "punch a folk singer" in the face.

Bob Dylan made those kinds of folkies obsolete when he went electric with the salient (if historically dubious) image of Pete Seeger rushing around backstage with an ax looking to cut the power cord, providing a potent symbol of the movement's intolerance. The folkies who survived in the popular imagination grew their hair long and/or hired drummers and started calling themselves singer-songwriters. They continued to flourish through the '70s, though some critics caught on (see Lester Bangs' 1971 essay "James Taylor Marked for Death," which is really more about The Troggs).

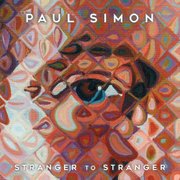

But I love Simon's music, even if I'm not sure I approve of his business practices and probably would find him insufferable at a dinner party. The jerk's music means a lot to me and I'm only a little surprised to discover his new album, Stranger to Stranger (Concord), feels like the best and freshest thing I've heard all year. I can't stop playing a couple of the tracks, the infectious "Wristband," a collaboration with African-inspired Italian electronic music producer Clap! Clap!, and the slippery "Cool Papa Bell."

It's encouraging and shocking to realize that Simon is 74. It shouldn't be. He hasn't gone off on a long spaceship ride and come back younger or anything; the math remains the same. He was a teenager when I was born and closing in on 30 when I started buying his records.

He was in Simon & Garfunkel then, rock 'n' roll kids who probably became folkies because of certain record business realities, and their greatest hits was one of the first albums I bought. In the circles I traveled in then, it was cool to be a folk singer, even though Dylan had already spit the bit.

...

What really killed off the folk singer as a viable symbol of cool was the instant when American popular culture spun back on the earnest pieties of hippiedom. You can watch it happen in John Landis' 1978 movie Animal House, when Bluto Blutarsky (John Belushi) is descending the frat house stairs during the toga party. There's a sweater-wearing "Charming Guy with a guitar" (singer-songwriter Stephen Bishop) sitting on the steps, surrounded by some obviously infatuated coeds (one of whom happens to be Belushi's wife Judy, who also helped sew the togas for the scene).

Charming Guy is singing -- adagio -- a 500-year-old tune called "The Riddle Song," which includes the lyrics "I gave my love a cherry, that had no stone/I gave my love a chicken that had no bone." Bluto stops, apparently listening intently to the performance. For a moment, it appears that he may be deeply affected by the tune.

Then he takes the guitar from C.G. and smashes it -- once, twice -- against the wall. Then he hands the neck back and, with an almost imperceptible shrug, tells the singer, "Sorry."

In theaters in the summer of 1978, the scene drew not only laughs but cheers. Nihilistic Bluto triumphed against the sensitive blandishments of singer-songwriterdom. Say what you will about the cultural significance of the Sex Pistols -- as manufactured an act as the glorious Monkees -- the guitar-smashing scene was symbolic of the repudiation of the more flowery aspects of '60s counterculture in favor of an ironic prep school smirk. This is where a certain kind of postmodern sensibility, the reflexive snarkiness that finds any show of sincerity absurd, begins.

The scene was largely accidental -- Bishop has often said that he was surprised the first time Belushi grabbed his guitar and smashed it. (The scene was filmed twice; Bishop had the shards of the second guitar signed by the cast and framed.) He was cast in the film because he was a friend of Landis' -- he appeared in several of the director's movies, always credited as the "charming" something or other. He was playing "The Riddle Song" because it was in the public domain; the budget was too small to pay for licensing another period-correct song (Animal House was set in pre-Beatlemania 1962).

Bishop was something of a pop star at the time. His debut album, 1976's Careless, produced a couple of hits ("On and On" and "Save It for a Rainy Day," the latter featuring Chaka Khan and Eric Clapton) that undermined the rhythmic intelligence and genuinely funny lyrics elsewhere on the album. Bishop was anything but the naive proto-punk garage rocker Bluto might have aligned with -- he was the dweeby dude who brought his acoustic guitar to a toga party.

By 1977, Bishop was a music business professional; he'd been "discovered" by none other than Art Garfunkel when he was working as a $50-a-week songwriter for a Hollywood music publisher. Garfunkel recorded Bishop's "The Same Old Tears on a New Background" and "Looking for the Right One" on his second solo album, 1975's Breakaway, which also featured the Simon and Garfunkel reunion duet "My Little Town." (When Garfunkel hosted Saturday Night Live in March 1978, a couple of months before the release of Animal House, Bishop appeared as musical guest on the show. He also appeared as himself in a skit, begging a doorman -- Belushi, again -- to let him backstage at a KISS concert. When Bishop identifies himself as the guy who sang "On and On," the doorman bans him on the grounds that he hates that song.)

Oh, and one more fact that might prove interesting. While Landis prevailed upon long-standing family friend Elmer Bernstein to score Animal House (and to score it as though it was a serious drama, which baffled the composer even as he complied with it), Bishop wrote and performed the movie's theme song and a wonderful Frankie Valli pastiche that utilized his falsetto called "Dream Girl."

If you listen closely to that track, three minutes and 52 seconds in, during the refrain, Bishop substitutes the words "Carrie baby" for "dream girl." He's said this was a shout-out to Carrie Fisher, on whom he had a tremendous crush. Fisher was dating Simon at the time.

(But don't feel too bad for Bishop. On the set of Animal House he met Karen Allen, who was in her first movie. They had a romance that lasted several years; his song "Separate Lives," which was recorded by Phil Collins and served as the theme song to the 1985 film White Nights, was inspired by their breakup.)

It's worth remembering that in his late '70s through mid-'80s heyday, Bishop was often compared to Simon. In a November 1978 profile of Bishop in Rolling Stone (headlined "The Uncool"), Cameron Crowe wrote that Bishop "initially made no impression on anyone other than a few critics who took the time to point out that (a) Bishop was a wimp and (b) he sounded like Paul Simon. (Bishop insists: 'I don't hear the similarities. Neither does Simon -- I asked him. I've ripped off McCartney more, anyway.')" If Simon has ever expressed his thoughts on Bishop, they're not instantly retrievable via Google.

The purpose of this piece is not to slag on Bishop, who is almost universally described as a bright and funny guy and who has had his songs recorded by, among many others, Johnny Mathis, Barbra Streisand and Luciano Pavarotti. While Bishop has enjoyed a long and lucrative career, his most significant contribution to the culture is likely to be that semi-improvised scene in Animal House in which Bluto metaphorically trashes pretty much everything Bishop seems to stand for -- the pretty, the professional, the carefully curated and recorded.

You can have Never Mind the Bollocks; Bluto Smash Guitar is the more important cultural moment.

...

Professionally made pop music is a lot like American innocence -- it's a renewable resource. For all the noise punk rock made, you look around and see the same old show business decadence afflicting music. These days most people think American Idol and The Voice are the way music is done now; you find an old song and sing it with a lot of histrionics while dressed funny. People clap and vote. But as Leonard Cohen suggested, most people "don't care that much for music." In the sweep of history, the show business model of rock 'n' roll is likely to overwhelm the authentic artistry of a few performers. In the long run, it might all be regarded as greasy kid stuff.

Still, there's something refreshing about being divorced from market expectations. If Bishop wants to make an album today, he doesn't have to worry about whether there's a radio-ready hit on it. In the age of Spotify and Pandora, it's probably not going to make him any money. (In recent years, it seems he's spent a lot of time rerecording his older songs, though his 2014 album, Be Here Then, is all new stuff. It's about what you'd expect -- the only slightly anomalous track is the opener "Pretty Baby," which has an Americana feel and bears some similarities to an old weird American ballad.)

Even when something gets obliterated, it's never really dead; someone is always willing to painstakingly glue the pieces back together. Rock is dead, someone said. Long live rock.

...

That Simon began his career as the consummate sweater-wearing folkie is evident from Wednesday Morning, 3 a.m., Simon & Garfunkel's 1964 debut, which included the subtitle "exciting new sounds in the folk tradition." Wednesday Morning, 3 a.m. may have been the first album I bought that turned out to be a genuine disappointment.

But Wednesday Morning, 3 a.m. consisted largely of songs that, while not quite as hoary as "The Riddle Song," were pretty much in Charming Guy's wheelhouse. Columbia was grooming the duo as the next Peter, Paul and Mary. The cover photograph featured the clean-cut duo in suits and ties in a Manhattan subway station, the diminutive Simon posing with an acoustic guitar. Simon wrote only four of the album's 12 songs (he is also credited with arranging "Peggy-O"and "Go Tell It on the Mountain").

The oft-told story is that the album stiffed and the duo dissolved, with Simon wandering to England, where he became a figure in the sympathetic folk boom there. (Some say he ripped off various English folkies.) Meanwhile, unbeknownst to the boys, a Columbia producer named Tom Wilson added drums and electric guitar to "The Sound of Silence" and released it as a single retitled "The Sounds of Silence." It became a huge hit in 1965; Simon returned from England (where he had recorded The Paul Simon Songbook) and the duo re-formed. Simon & Garfunkel became one of the signal groups of the '60s, before breaking up for -- sort of -- good in 1971.

Since then, Simon has been -- I'd argue -- one of the two or three greatest American record makers. He's been far more consistent than, if not as prolific as, Dylan. Simon's strongest material compares well with Bruce Springsteen (who's also put out a few indifferent albums). Simon really didn't hit his songwriting stride until after he and Garfunkel broke up. His string of solo albums -- Paul Simon, There Goes Rhymin' Simon, Still Crazy After All These Years, the criminally underrated Hearts and Bones, Graceland and The Rhythm of the Saints -- established him as an American composer of significance. After Dylan, he is perhaps the most important singer-songwriter to emerge from the candy-colored rubble of '50s rock 'n' roll. (Springsteen is younger; he didn't really make any significant records until the '70s.)

We're only six months in, but for what it's worth, Charming Guy with guitar seems to have produced a real contender for album of the year, albeit one that's far too complicated to be strummed out on the frat-house steps. In the liner notes, Simon explains how his new music employs the 43 "microtones" per octave "heard" by the late American composer Harry Partch. (Arkansas blues-based blues guitarist CeDell Davis, who typically uses a butter knife as a slide, also incorporates microtones in his music.)

To play some of the songs on Stranger to Stranger required the modification and even invention of new instruments, many of them percussive, resulting in complex and eerie, something atonal, settings for Simon's familiar soothing rhythm singing and guitar.

I guess I understand why, after all these years, some people might want to punch Simon in the face. But please don't smash his guitar.

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 06/05/2016