I don't know what kids do in the summer; probably they play Minecraft and start nonprofits to provide clean, safe drinking water to developing nations. When I was a kid, I was obsessed with baseball in a way that might have caused my parents some anxiety had they not been busy with their own lives.

I played it in organized leagues, on sandlots and by myself. Inside our garage, I perfected a rainy day game that involved throwing a tennis ball on one hop into the wall so that it rebounded on a flat trajectory I could swing at and (surprisingly often) hit. Depending on the quality of my contact, I awarded "the batter" a single, double or (rarely) a home run. A grounder or pop up was an out. A miss or a foul was a strikeout or foul out. (I don't know whether this game did anything for my reflexes or batting stroke, but I peaked as an athlete around age 12. I was a pretty good Little Leaguer.)

I played mostly as my favorite team -- the San Francisco Giants. I also batted for their opponents, priding myself on trying just as hard when I was impersonating the Braves' Hank Aaron (who had the supple wrists of a pinball wizard) as I did when I was Willie Mays. In summer 1968, I played the Giants' 162-game schedule, keeping score and stats in a yellow spiral notebook.

I also invented a dice-based game a lot like the Strat-O-Matic Baseball, which I always wanted but I was never allowed to order. It involved dice and sheets of "player cards" in five-subject, college-ruled spiral notebooks. I kept the stats for this league in yet another notebook, which probably caused my parents to think me more academically industrious than I was.

I also watched baseball on television -- in those days that generally meant just NBC's Game of the Week. My closest major league team, the Los Angeles Dodgers, severely restricted local broadcasts. My father, a lifelong Dodger fan, would take the family to a couple of games at Chavez Ravine every year. And when I visited my uncle in San Francisco, he always took me to a Giants game at Candlestick Park or -- after the team moved from Kansas City, Mo. -- an A's game in Oakland Coliseum.

There were Dodger radio broadcasts with Vin Scully on KFI and Dick Enberg on the California Angels network. And baseball cards.

But mostly I read about it. The Sporting News arrived every Monday in the mail; I also plowed through the works of Curtis Bishop (Little League Visitor, Little League Amigo, Little League Double Play, among others) and John R. Tunis (The Kid From Tomkinsville, The Kid Comes Back, Keystone Kids, et al.). I devoured the annual stats guides and the biographies of past and current players. I read about the Gashouse Gang and the Hitless Wonders. When I was 10, 11 and 12 years old, I could not only tell you the starting lineups for every current major league team, I was conversant with Duck Medwick's 1937 Triple Crown season. I knew all about Tony Lazzeri and Arky Vaughan.

Reading about baseball was even more satisfying than playing it or generating and curating my own fantasy statistics. The game nourished me, it made me happy.

...

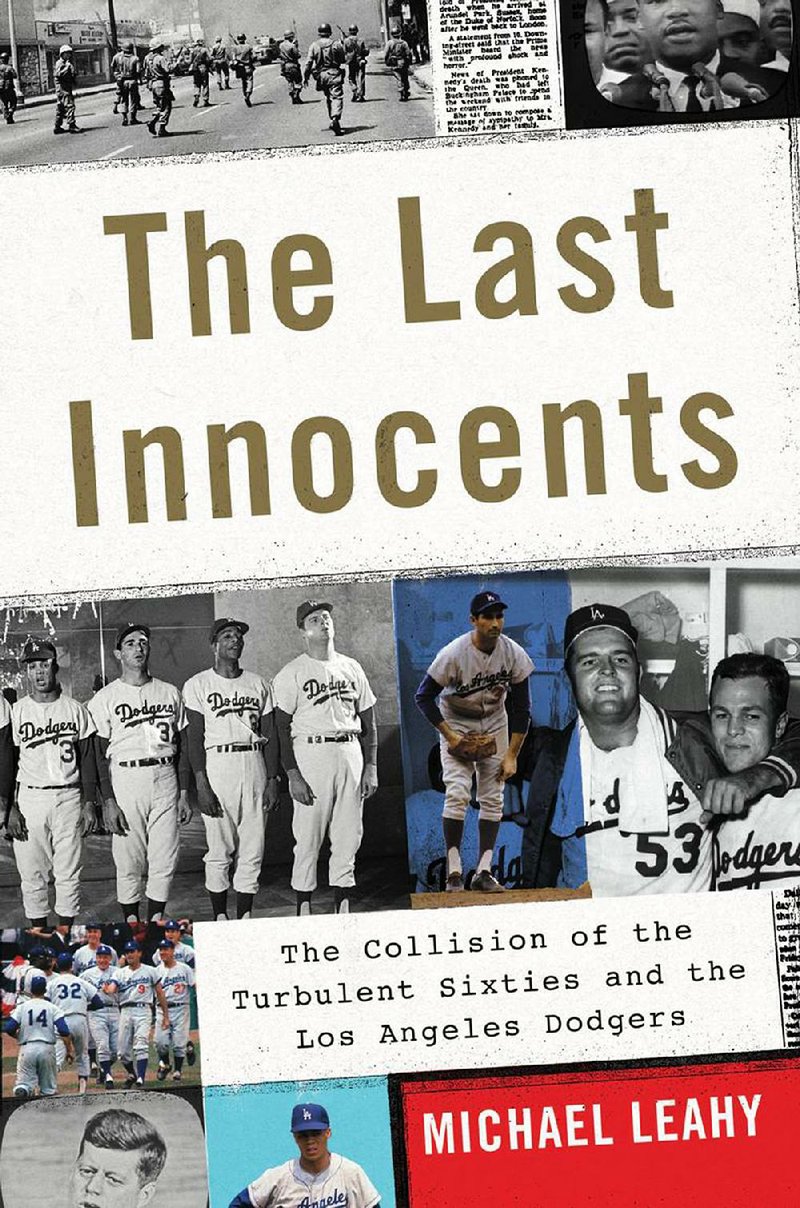

My former colleague Michael Leahy grew up in Northridge, Calif., in the San Fernando Valley, about an hour and a half away from where I lived in Rialto. He was closer to Dodger Stadium and probably made the trip to the ballpark more often. In the photo section of his new book, The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers (Harper, $26.99), he includes a blurry photo he took as a 12-year-old of Sandy Koufax warming up. While Leahy is doing the work of a historian here, he is also a susceptible witness -- a fan. Worse than that, he is a fan exhuming his own nostalgia.

And mine.

The Last Innocents made me happy in the uncomplicated way that those books I read when I was 10, 11 and 12 made me happy, though it is not an uncomplicated book. In many ways, the book is a debunking of the Dodger myth, as it reveals the anger and dissatisfaction of figures I had taken for dull saints. As it turns out, Koufax, John Roseboro and the banjo-playing Maury Wills were more than their brand images; they were complex human beings who sometimes chafed at the way they were treated by Dodger management. Nor were they oblivious to the changes in American society that were occurring all around them in the '60s.

I like and admire Leahy, who I worked beside for a couple of years. I'm predisposed to like his book, so consider that before you run to your local bookseller. But also consider that I have cause to be jealous of Leahy -- a splendid writer with what feels like a free-flowing, friction-less voice (though I remember how, when he was at this newspaper, he re-worked his columns in longhand on foolscap paper and scribbled changes in the margins of proofs). His just-published book is bound to sell decently and receive good reviews. Besides, he was in the stands when Koufax threw his perfect game against the Cubs in 1965.

By the time Koufax pitched that perfect game, he was being held together by shots of painkillers and the anti-inflammatory butazolidin ("bute"). He would pitch only one more year in the majors, retiring after the 1966 season at the age of 30. It's an old story, maybe best told by Jane Leavy in her 2002 book Sandy Koufax: A Lefty's Legacy. He's probably an authentic mensch, legendarily decent and spotlight shy, no more or less than what we believe him to be. (Koufax's myth is such that he still commands an odd deference. In May, the New York Post's Page 6 gossip column ran an item about the 80-year-old Koufax not being recognized when he bought a slice at a well-known Soho pizzeria.)

But I did not know about Wills and Doris Day. Apparently they dated, but Wills broke it off after Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi suggested it might be bad for his -- and the team's -- image.

It turns out that Wills, a fiery player whose daring base running made him a stylistic heir of Jackie Robinson, could be intimidated off the field. Leahy describes how he was consistently frustrated in contract talks with Bavasi, who emerges as a villain who masked his ruthlessness with outward bonhomie. Bavasi wouldn't allow agents; his one-on-one negotiations with the Dodger stars were one-sided routs.

In an era when free agency wasn't an option, multi-year contracts were rare and management held all the cards, Bavasi held the Dodgers' payroll down by refusing to negotiate. Typically he'd let a player make a case for a raise, then counter by producing a contract with the team's figure written in. "Here's your contract, let's wrap this up," he'd say.

Wills, who spent eight years in the minor league before getting a shot with the Dodgers, invariably caved, and came out of these meetings seething with self-loathing and resentful of the organization. Meanwhile, Bavasi bragged about his tactics to friendly beat writers, and the Dodgers -- who were setting attendance records -- became one of the most profitable franchises in pro sports. While Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals signed the first $100,000 per year baseball contract in 1958 after seven years of no pay increases -- a span in which he won three batting titles (1951, '52 and '57) and a RBI crown (1956), and hit .310 or better with at least 21 home runs each year -- no Dodger was able to crack that barrier until Don Drysdale and Koufax staged a joint holdout before the 1967 season. (Wills finally got to $100,000 as a 39-year-old backup infielder in 1972, his final season in baseball.)

(In a piece that ran in Sports Illustrated in 1967, Bavasi wrote: "To tell the truth, I wasn't too successful in the famous Koufax-Drysdale double holdout in 1966 ... when the smoke had cleared they stood together on the battlefield with $235,000 between them, and I stood there with a blood-stained cash box. Well, they had a gimmick and it worked; I'm not denying it. They said that one wouldn't sign unless the other signed. Since one of the two was the greatest pitcher I've ever seen ... the gimmick worked. But be sure to stick around for the fun the next time somebody tries that gimmick. I don't care if the whole infield comes in as a package; the next year the whole infield will be wondering what it is doing playing for the Nankai Hawks.")

...

Leahy also illuminates journeyman outfielder Lou "Sweet Lou" Johnson, who stepped in to play left field for the team in 1965 after regular left-fielder Tommy Davis (a two-time batting champion who was one of the team's few legitimate offensive threats) broke his ankle. Johnson became a pivotal part of the 1965 team, which went on the defeat the Minnesota Twins in the World Series (the series in which the Jewish Koufax declined to pitch the opening game because it fell on Yom Kippur). After Davis returned for the 1966 season, Johnson moved to right field, where he enjoyed the best season his career.

Like a lot of black players, Johnson saw the Dodgers as the most progressive of teams -- under Branch Rickey they had broken the color barrier. But they couldn't protect him from indignities inflicted in Vero Beach, the Florida town where the Dodgers held (and still hold) spring training. There Johnson was as unwelcome as any other black American. Johnson couldn't wash his clothes in a Vero Beach laundromat so the Dodgers installed their own washers and dryers. But when a reporter asked Johnson why he swung so furiously at every ball, he surprised himself with his honesty: "Because it's f--n' white."

...

I don't know how useful it is to try to fit the stories of the seven players Leahy chose to weave into a critique of the turbulent decade; the '60s (which may have begun with the assassination of John F. Kennedy in November 1963 and ended with the resignation of Richard Nixon in 1974 or the effective demise of baseball's reserve clause in 1975) changed things. Any cultural history of any American sports team or institution would reflect the tumult of the decade, but for people like Leahy and myself, who experienced the decade as children, it can sometimes be difficult to reconcile the illusory purity of the way the game felt with the reality of adults who played the game.

I never thought about players like first baseman Wes Parker -- who emerges as a fascinating, thoughtful man who is very different from the image I conjured up from the back of his baseball card -- or the inherently decent catcher Roseboro having off-the-field lives. I never imagined that Roseboro gathered weapons to protect his home and family from rioters. I had a vague ideal of Parker's background, enough that I'd dismissed him as a princeling for whom things came quite easily. The Last Innocents disabused me of that too easy notion.

On the other hand, what I found most intriguing about the book were the on-field anecdotes -- the account of Wills' spiking of the Braves' Joe Torre says a lot about the characters of both men, and the way our games (and times) have changed. American innocence has always seemed a renewable resource , something lost and recovered in cycles. But it was different in those times. They were Giants.

And the rivalry between the teams -- which became a blood feud Aug. 22, 1965, when (my hero) Juan Marichal clubbed Roseboro over the head with a bat after Roseboro whizzed a ball past the pitcher's nose while he stood at the plate -- is there too. Leahy suggest that maybe Roseboro took this action because Koufax had declined to throw at Marichal in retaliation for the Giants' pitcher hitting Dodger outfielder Ron Fairly earlier in the game.

I can't believe that game was 50 years ago. Or that it was the first game the Dodgers played on the road after the Watts riots started. I remember both events, but the riots seem so long ago. But maybe because I didn't watch it on TV, Marichal's brutal, shameful act seems much closer.

The Last Innocents might not tell us anything we think that we don't know about the '60s. But it took me back to a place I haven't often been since then, where baseball is an alternate universe, deeper and more detailed than Narnia or Westeros, into which we kids might for a time escape.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 06/12/2016