Old News has been ransacking the archives of the Arkansas Gazette to learn about a long-dead murderer, Lee Blount.

Was he a thug or was he the pawn of circumstance? All I know is what I read in the newspaper.

On June 13, Old News covered the heavily reported escapes that distinguished Blount's early criminal career. Here's what happened after he was sentenced in 1915 to 18 years for killing Faulkner County Deputy Sheriff Oscar L. Honea: He escaped.

In January 1916, with temperatures dipping into the 20s, prisoners in the middle of three camps at the state prison farm in Lincoln County, Cummins, used a steel table knife to cut through 2-by-8-inch board flooring in the lavatory of a new stockade building. One by one about 8 p.m. Jan. 19, a Wednesday, 24 prisoners dropped through that hole into an ample crawlspace. They pulled the boards into place above them, and the breakout wasn't noticed until midnight.

The warden of this camp had recently been fired by the governor because of cruelty to inmates. And there were about 1,300 prisoners at Cummins.

Five of those who "dashed to liberty" were found "haggard and bedraggled" within hours. Ten were in custody before week's end. Blount and the rest appeared to have vanished, the Gazette reported Jan. 23.

But Jan. 25, a week after the escape, the paper carried an interview with him from Mayflower, where he'd been staying at his father-in-law's home since Saturday. He was strolling around the village. That was bold, considering the mob of angry people in nearby Conway who thought he should have been executed for killing Honea.

"I wanted to see my wife and baby," Blount told his friends.

He had wired bricks to his feet "to baffle bloodhounds," hopped a train to Argenta (North Little Rock) and walked the rest of the way through woods, wearing his prison stripes all the way.

Blount claimed he had written to the state farm offering to surrender -- if his wife got the $50 reward. And this turned out to be true.

He told the Gazette he would "hobo" to Little Rock and turn himself in. But to prevent a lynching, Deputy U.S. Marshal C.O. Payne and R.G. Anderson, a clerk of the penitentiary commission, instead met him in Mayflower, in a storefront, at midnight.

By the light of one kerosene lantern, Blount's pals insisted that Anderson first hand over the $50, which they counted, and then Blount strolled in. He also

counted the cash. Then he went peaceably.

On the way to Little Rock, the motorcar was repeatedly mired in mud, and six times Blount wielded a long pole to pry it free. "We went after Blount but it must be admitted he brought us back," Anderson said.

SECOND ESCAPE

In June 1916, while working in a newly cleared cotton field on the state prison farm at Tucker in Jefferson County, Blount and two other men reached the end of a row and "jumped" into the woods.

The next day at Stuttgart, "the nonchalant Mr. Blount" strolled up to some of the many men hunting him, including J.A. Heffington of the Little Rock Tent and Awning Co. "Hello fellows, what are you doing down here?" Blount asked.

Since he was surrounded, he decided to go back, and by the way, do the state the favor of telling them where they could find a stolen horse.

Heffington told the Gazette Blount made a "favorable" impression. Blount "declared that he had told the guards repeatedly he would not try to escape again and that he was willing to serve his term, but that he was made to work so hard he could not stand it and so he was tempted to run away."

Having read a bit about those notorious farms, I can believe it. See the Old State House podcast video at bit.ly/1ZLQ2ja.

ARTISTIC LICENSE

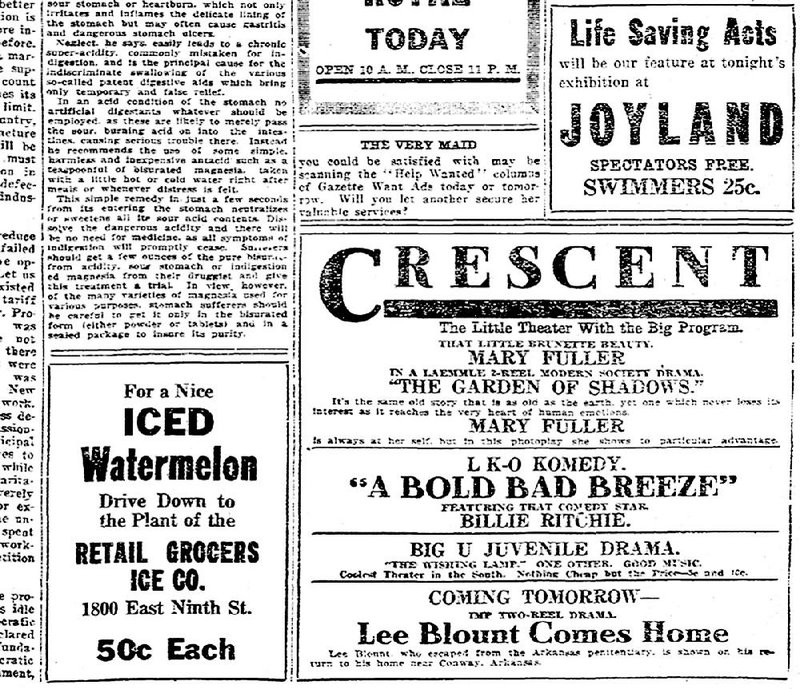

On Aug. 1, 1916, the Gazette reported that a "two-reel motion picture play" titled Lee Blount Goes Home was set to show at the Crescent Theater in Little Rock. Since he was considered "a bad actor," Blount's part was being played by Herbert Rawlinson, a "well known motion picture actor." (Which he was.)

"It is said the film drama shows Blount's escape from the penitentiary, his return home, his meeting with his wife and his recapture by 'Foxy Dick' Anderson, clerk of the Penitentiary Commission," the Gazette reported. "The play is described by the gifted press agent as 'a wonderful, original story of heart interest to all.'"

According to its plot summary at imdb.to/260Ge8v, it presented Blount as totally innocent, framed by a false friend who lusted after his wife, Jane.

We can only wonder what Blount's wife, Eliza, made of that.

DESPERADO

I estimate that Blount was 34 when he escaped yet again, Jan. 31, 1917. He and a bank robber named James Stewart, aka Shorty Defts, turned the shotgun with which Blount had been entrusted (!) on a rather lucky field supervisor. The blast merely tore his trousers.

A month later, at noon March 1, Blount and Defts robbed a bank in Collinston, La., and fled on horseback. The town mayor, H.W. Vaughn, quickly mounted a posse in pursuit, and in their haste, the robbers dropped a bag containing $3,000.

Vaughn had a fast horse and soon rode up beside Blount. The mayor took aim, but his gun misfired. Blount shot Vaughn's horse. As the mayor crouched behind it, Blount put a bullet in his brain, from behind.

The posse brought Blount to bay in a tiny church whose black congregation, I assume, was not present on Thursday afternoons. The posse riddled the place with bullets, but he refused to come out. So they set it on fire. He came out.

He had squirrel shot in his face, a bullet in each leg and another through his belly.

For weeks he lay manacled to a bed at a charity hospital in Shreveport, while the tone of Gazette reporting underwent a dramatic shift: "Death Draws Near For Noted Bandit." "Pathos fills the last hours of Lee Blount." Readers learned that he called for a minister and was baptized, that the leg irons "hurt him more than the fatal wound in his abdomen," that he apologized to a nurse:

"I won't give you any more trouble for you folks have been mighty good to me, better I reckon than they are to most folks in the sort of fix I'm in and better than I ever thought folks like Shorty and me are treated. I want you all to know I'm thankful and that I'll try to behave myself until I'm not able to behave in anyway."

At 7:45 p.m. March 21, he died from "erysipelas" -- blood poisoning. "The largest crowd that ever attended a funeral in Mayflower" turned out to bury "the Faulkner County desperado."

And that was the last of him -- except for this: In 1931, his son, Freelan Blount, 17, was sentenced to the Arkansas Industrial School for Boys on a charge of forgery.

The things men don't do live on after them.

Next week: Pity the unemployed, unemployable girl.

ActiveStyle on 06/20/2016