The Arkansas Supreme Court ruled Thursday that the state can move forward on executing eight death-row prisoners. However, the state has only six days until one of the execution drugs it has on hand reaches its expiration date.

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

RELATED ARTICLE

http://www.arkansas…">Law inducing judges to quit at 70 upheld

In a 4-3 ruling that drew three separate dissenting opinions, the majority of the high court reversed a 2015 decision by a Pulaski County circuit judge that found the state's revised execution law unconstitutional.

The now-validated execution law requires that three drugs be used in carrying out executions. The state's supply of one of those drugs expires June 30, and prison officials have had no luck finding more.

In addition to prison officials, the spokesmen for the governor and the attorney general were unable to say Thursday whether a new source of the drug has been found.

Thursday's ruling is not effective until the high court issues a mandate, a process that usually takes 18 days to allow attorneys time to petition the high court for reconsideration.

On Thursday, Judd Deere, a spokesman for Attorney General Leslie Rutledge, said the office is reviewing all options and hadn't requested that the court expedite its mandate.

An attorney for the inmates, Jeff Rosenzweig, gave the following statement:

"We are disappointed in the decision of the court. We are studying the decision and anticipate filing a petition for rehearing."

Deere said Rutledge was pleased with the court's ruling, which came more than a month after the case was orally argued and submitted to the court. When asked if Rutledge was disappointed that the decision came so close to when the drug is to expire, Deere said that was a court matter.

A spokesman for Gov. Asa Hutchinson, who in September scheduled the eight inmates' executions, said the governor was pleased with the ruling and is coordinating with Rutledge's office over how to proceed.

"Obviously this decision was made. It was handed down obviously very close to the [drug's expiration date]. ... There's no specific next step right now," Hutchinson spokesman J.R. Davis said. "Obviously, more time would have been beneficial. What we have now is a ruling. We have to act. ... We have to look at what the next steps have to be."

Davis said that given all of the procedural and time constraints, he wouldn't "speculate" about when an execution will be carried out.

Once the Supreme Court issues a mandate, that will lift the stays of executions. The attorney general's office would then ask the governor to set execution dates, and the inmates in question would be entitled to petition the Parole Board for clemency.

Because of a series of legal challenges and unavailability of execution drugs, Arkansas hasn't executed a prisoner since 2005.

Act 1096 of 2015 established the execution procedures and the three-drug cocktail that's to be used by the Department of Correction to carry out the death penalty.

The law also keeps the source of the state's execution drugs confidential. Prison officials argued that secrecy was necessary to protect the drugmakers and vendors from public backlash associated with state-sanctioned killings.

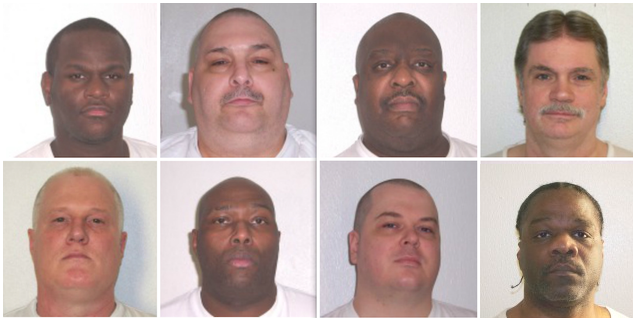

On Sept. 28, 2015, just weeks after Hutchinson scheduled their executions, the eight inmates in question -- plus one more on death row -- sued prison officials, challenging the legality of not disclosing the drugs source and of the execution protocol.

In early December, Circuit Judge Wendell Griffen ruled in favor of the inmates, saying the law violated the Arkansas Constitution. He ordered prison officials to disclose the source of the drugs.

The Supreme Court stayed Griffen's order. On appeal, state attorneys argued that Griffin's order was invalid because the inmates' attorneys did not prove that the law violated the constitution. They also argued that prison officials are protected by "sovereign immunity."

The inmates' attorneys argued that the Supreme Court couldn't take up the appeal because Griffen didn't rule on sovereign immunity.

On Thursday, Justice Courtney Goodson, writing for the majority, said Griffen did rule on sovereign immunity by rejecting arguments from state attorneys that prison officials are immune from being sued.

In his dissent, Justice Paul Danielson argued that the Supreme Court should have dismissed the state's appeal of Griffen's ruling because Griffen did not make an explicit finding on the issue of sovereign immunity.

"This court has been clear that it will not presume a ruling from the circuit court's silence, as we have held that we will not review a matter on which the circuit court has not ruled, 'and a ruling should not be presumed,'" Danielson wrote.

The prisoners have argued that the drugs, in particular Midazolam -- which has been linked to much-publicized botched executions -- could result in an unnecessarily painful execution, violating a prisoner's rights to be free from cruel and unusual punishment.

Goodson wrote that to support such an argument, the prisoners would have to prove that the state's execution protocol is "sure or very likely to cause ... needless suffering" and that any alternative means of execution is less risky and "available" to state officials.

The prisoners' attorneys argued that the standard posed by Goodson didn't apply in their case.

In their arguments, the prisoners' attorneys also pointed to the state constitution's provision that prisoners are free from "cruel or unusual" punishment, while the U.S. Constitution's Eighth Amendment protects citizens from "cruel and unusual" punishment.

Goodson said she was "not convinced" by the argument involving the "slight variation" in the language and that the court would adhere to federal standards on the issue.

Goodson sided with state attorneys, who argued that the prisoners' offerings of alternatives to the three-drug cocktail -- which included proposals of death by firing squad, gas chamber or other drugs -- did not meet the burden of proof to be found viable and available.

Justice Robin Wynne disagreed. In his dissent, he wrote that the prisoners had laid out several execution alternatives that should go back to circuit court for further arguments.

Justice Jo Hart also disagreed. She wrote that the majority didn't follow the court's own standard for review of motions to dismiss. The court should have treated the evidence alleged by the prisoners in a light most favorable to the prisoners, the party who filed the complaint, she wrote.

Hart also argued that Goodson and other justices made a mistake by ignoring the difference between "and" and "or" in the federal and state constitutions.

Citing the late "originalist" constitutional scholar U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, Hart wrote:

"The conjunctions and and or are two of the elemental words in the English language. ... And combines items while or creates alternatives. Competent users of the language rarely hesitate over their meaning," Hart wrote. "The distinction is dismissed by the majority, and this case serves as an unfortunate precedent for future cases involving the interpretation of statutes, contracts, or the state constitution."

Griffen had agreed with arguments by the inmates that their rights to due process were voided by the drug-secrecy provision in the execution law.

Goodson wrote that although the prisoners were not privy to the source of the drugs, prison officials had the drugs independently tested and verified. The inmates didn't need to know who supplied the drugs, Goodson wrote, suggesting that they needed to know that the drugs met potency requirements.

Goodson's opinion also reversed Griffen's ruling that found that the secrecy provisions run afoul of the state's version of the First Amendment ensuring freedom of speech through "openness and debate."

Goodson wrote that though such information was subject to disclosure in the past, the "practical realities of the situation" made disclosure detrimental to acquiring the drugs needed to fulfill state law.

She also wrote that the law did not run afoul of the publication clause of the Arkansas Constitution, which requires that an "accurate and detailed statement" of public expenditures "shall" be published.

Goodson wrote that lawmakers can "determine the time and manner for the disclosure of public expenditures" and that the execution law's disclosure ban is in keeping with that.

She also noted that the law was crafted with an exception that provided for disclosure of the source of the drugs by prison officials if a group or person was willing to enter into a protective court order.

Wynne, in his dissent, wrote that Goodson's opinion legitimized "overreach" from the legislative branch.

The state constitution "requires that the information be published. To publish something is to declare it publicly or make it generally known," Wynne wrote, citing a Webster's dictionary entry. "Essentially, the majority is saying that a requirement for certain information to be publicly declared is satisfied if a state agency first gets an order prohibiting the information from being made public."

Wynne added: "This makes absolutely no sense whatsoever."

A Section on 06/24/2016