Most of us love outdoor pursuits such as hunting, fishing, camping, hiking and canoeing. Yet even though we consider ourselves “outdoor types,” few of us possess the skills and knowledge once considered basic by all true woodsmen. Could you, for example, start a fire with a single match? Could you quickly build a shelter that would protect you from wind and cold? Would you be able to find your way back to a vehicle or camp without a GPS or a map? Could you find wild foods to sustain you? If your life depended on it, could you?

Unfortunately, knowledge of these “woodsman’s ways” is increasingly uncommon. If forced by calamity into a survival situation, many people would find it difficult to stay warm and healthy. Some might even perish.

Wise outdoorsmen take time to learn important outdoor skills before they find themselves in a bad situation outdoors. It can happen to anyone, including you. So study these tips, and practice them outdoors before your next trip afield.

How to build an emergency bivouac shelter

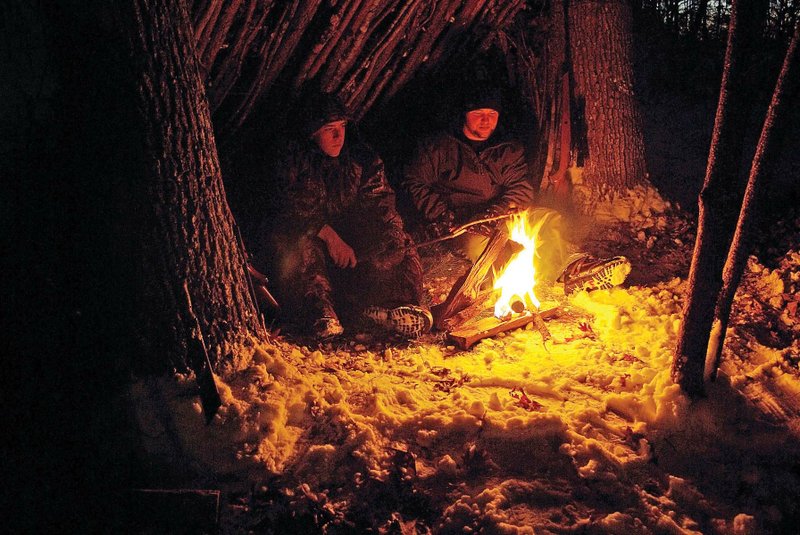

Bough structures that reflect a fire’s warmth, serve as windbreaks and provide overhead shelter are important emergency shelters. They can be erected without tools in an hour in an area with downed timber — less if you find a makeshift ridge pole such as a leaning tree to support the boughs.

Step 1: Wedge a ridge pole (a horizontal cross piece) into the lower forks of two closely growing trees (one end can rest on the ground, if necessary), or support the ends of the ridge pole with tripods of upright poles lashed together near the top.

Step 2: Tilt branches or poles against the ridge pole to make a frame. To strengthen this, interlace limber boughs through the poles at right angles.

Step 3: Thatch the lean-to with slabs of bark and/or leafy or pine-needle branches, weaving them into the framework. Chink with sod, moss or snow to further insulate the structure.

One-match fire

Lighting a fire should be accomplished with a single match if possible. Even when plenty of matches are at hand, this skill may someday mean the difference between a warmly comfortable camp and a chilly, miserable one.

Ordinary wooden matches are best and should be kept in a waterproof, unbreakable container. Place a softball-size piece of tinder on a slab of dry bark or the ground. Good tinder ingredients include lint (check your pockets and belly button), cotton threads, dry-wood powder, unraveled string, bird or mouse nests, dry splinters pounded between two rocks, dry shredded bark or pine needles, and slivers of fat pine.

After the tinder is laid, pile a handful of small dry twigs (preferably evergreen twigs) above this. Over this nucleus, lean a few slightly larger seasoned branches. Also in tepee fashion, so ample oxygen will reach all parts of the heap, lay up some big pieces of dead wood.

With the fire pile sheltered from wind and rain, ignite the tinder so the flames will eat into the heart of the pile. When the fire gets going well, you can shape it any way you want.

Finding your way

If you get should lost and don’t have a compass, it’s important to know how to get your bearings so you can travel the right direction to your vehicle, a camp or to civilization.

If you are in the Northern Hemisphere, you can use the North Star to locate north. To find it, locate the Big Dipper; then follow the line made by the two stars that form the front end (opposite the handle) of its “cup.” These point to the North Star (Polaris), which always lies directly over north on the horizon.

Another way to determine direction without the aid of a compass is to drive a straight 3-foot stick into the ground in a sunny location, and set a stone at the tip of the stick’s shadow. Wait 20 minutes; then place another rock where the tip of the shadow has moved. The first marker indicates the west end of a line running between the two rocks; the second marks the east.

Foraging for wild edibles

One mark of an expert forager is the ability to rustle up a square meal from nature’s larder in the dead of winter. It can be tough to gather wild foods when the landscape is covered with ice or snow, but knowing some commonly found winter victuals can help you find sustenance even under adverse conditions.

A pound of acorns provides 2,000 calories of food value, so one shouldn’t overlook these oak nuts as an important winter food source. Crack them out of their shell, break large pieces into pea-sized chunks, then soak in several changes of warm water for several hours to remove the bitter tannic acid. When a taste test shows they have a bland flavor, let the acorns dry for several hours; then roast and eat, or grind to make acorn flour. The flour can be used to make a nutritious acorn porridge or hard, brown biscuits.

Watercress — most fair-weather foragers are familiar with this pungent green, which grows in the clean cold water of springs and slow-moving streams. But few know that a well-established patch of watercress will do quite well even in the middle of winter. Pinch or cut the plant off just below the leaves, wash thoroughly, then use fresh in a salad, steamed and eaten as a vegetable or as a peppery ingredient for soup.

Wild garlic and wild onions can both be found poking up out of grass year-round, especially in more temperate regions. Use them like their cultivated relatives, alone or to add flavor to other dishes.

Chickweed ranges throughout Arkansas, and from Alaska to Florida and all points between. Chickweed flourishes in open, sunny areas, even in frigid climates, and is easy to identify with its little starlike flowers. It’s delicious raw or cooked as a potherb and has a mild flavor with just a little tartness.

Mussels and clams, freshwater and saltwater, often can be gathered in quantity and cooked to make a chowder or seafood dinner. Watch for piles of shells left by marauding raccoons or muskrats, a sign that a bed of these mollusks may be nearby.

Learning survival skills such as these is not only an insurance policy, but a way of getting back in touch with nature. It can be an adventure in which you discover not only how to survive in unexpected situations, but how to live well — whether you’re fishing solo on a backcountry river, hunting with friends on a deer lease or camping with family in a park near home. Study these tips, and you will discover you can do things you never dreamed you could do. And at particularly high moments, you will feel a real connection to the natural world around you.