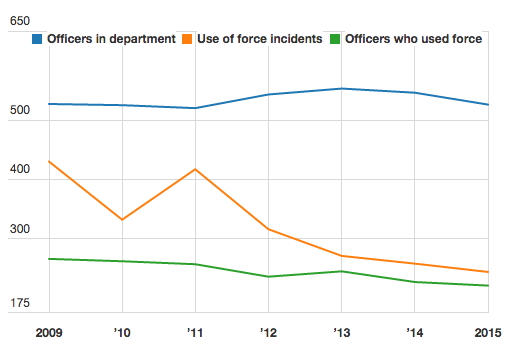

Little Rock police data show use-of-force incidents decreased a fourth straight year in 2015 as the department moved toward community-minded policies and training recommended by the federal government.

Police Chief Kenton Buckner said the department has emphasized restraint and communication over physical force, in accordance with principles outlined by The President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

He said Tasers have played a major role in the use-of-force decline, as well, deterring countless confrontations since Little Rock police began equipping more officers with the electro-shock weapon in 2011.

"We're creating an environment and a culture that says we can be proactive, we can be assertive," Buckner said. "But force is a last option if we're put in a situation where we have an opportunity to de-escalate, to talk someone down or to use other methods to get them to comply with what we're asking them to do."

Department policy defines force as physical contact used to subdue an uncooperative suspect. Approved methods progress from soft hand grips to deadly force, such as gunfire. Taser and pepper spray use fall in the middle of the use of force progression.

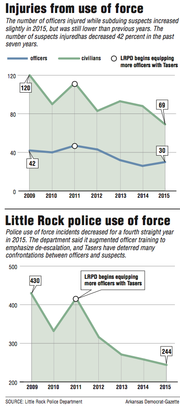

There were 244 incidents in which Little Rock police used force last year, according to data released under the state's Freedom of Information Act. That's 14 fewer than in 2014, and 27 fewer than 2013. No suspects were killed in police encounters last year, compared with five in 2014 and six the year before that.

Use-of-force figures hovered above 300 in previous years and often passed 400. Data show that use-of-force has decreased 42 percent since 2009, when officers used force on 430 occasions.

There have been no major revisions to the department's written policy on use of force since Buckner was sworn in as chief in June 2014. But Buckner said the department's philosophy on the matter changed after civil unrest in multiple U.S. cities related to police use of force.

The department has augmented its training to follow suggestions of The President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which President Barack Obama formed in December 2014 to "strengthen community policing and trust among law enforcement officers and the communities they serve."

The task force -- composed of police chiefs, community activists and legal scholars -- was organized after a white police officer, Darren Wilson, fatally shot an unarmed black man, Michael Brown, 18, in Ferguson, Mo., and sparked prolonged civil unrest in the St. Louis suburb.

In its final report, released in May 2015, the task force outlined methods for police to promote trust and legitimacy, improve communication through technology and social media, and increase officer safety. Increased accountability and transparency were also major themes of the report.

"Law enforcement culture should embrace a guardian -- rather then a warrior -- mindset to build trust and legitimacy both within agencies and within the public," the report states.

Little Rock police officers approached their job with a different mentality in the past, training division commander Capt. Heath Helton said.

"The old philosophy was, kind of, 'ask, tell, make' -- I'm going to ask you, I'm going to tell you, and then I'm going to make you," he said. "That concept, several years ago, might have been applicable. Now, I think as a society, things have changed. The laws have changed. I think society's views have changed on a lot of things."

Last year, the decrease in use of force yielded fewer injuries to suspects. Sixty-nine were hurt in police encounters, compared with 88 in 2014 and more than 100 in several previous years.

Thirty officers were injured while subduing suspects last year. That's a slight increase compared with the 26 recorded in 2014, but still lower than past figures.

The most common injuries to police and suspects were cuts and bruises. No one on either side of the badge was critically injured.

Officers are required to train annually in use-of-force techniques. Along with refresher courses on hand control tactics and weapon use, they study legal issues and notable cases of deadly force, with guidance from the city attorney's office.

In training last year, police began emphasizing a communication tactic known as verbal de-escalation. Effectively, the technique steers an encounter away from conflict and toward a resolution. Helton said it often boils down to something simple that police in many cities have been criticized for not doing -- listening.

"Part of our verbal de-escalation is don't be willing to go hands on so quickly. Listen to what people are saying," he said. "Sometimes when people are aggravated and agitated, it's good to let them vent because when they're venting, they're calming themselves down."

That training also includes direction on interacting with the mentally ill. Officers now have the option to transport certain people to mental health clinics and substance-abuse treatment centers.

"We're taking the time and having our officers slow down, analyze that situation a little bit more and see if this is an individual that doesn't really need to go to jail, and do we need to divert them to a location that would better help them," Helton said.

Studies have found the mentally ill constitute a significant percentage of those killed by police. A Washington Post analysis of 1,000 fatal police shootings in 2015 found that about one in four involved a person with mental health problems.

A 2013 study by the Treatment Advocacy Center and the National Sheriffs' Association assessed justifiable homicides between 1980 and 2008 and estimated that about half of those fatally shot by police during that time were mentally ill. The study was based on informal research and accounts, and noted that national data were not available.

The FBI did not track police shootings until this year.

There were no police shootings in Little Rock in 2015, though officers fired at suspects on five occasions. Each instance of deadly force was ruled justified.

Officers used pepper spray 28 times last year, fewer than the 40 instances in 2014. Compared with the 123 instances logged in 2009, it's a 77 percent decrease.

The use of Tasers decreased last year, as well, though more officers were equipped with the weapon. Officers Tasered suspects on 32 occasions, compared with 40 in 2014.

Helton said about 98 percent of the Police Department's 526 sworn officers had been assigned a Taser, as of this month. The department owned just 25 Tasers in 2011, when it distributed the weapons between supervisors and special units.

The city began making bulk purchases of the weapons that year through increased local tax funds and a federal Justice Assistance Grant. Police said the purchases have amounted to $721,561.86, including replacement cartridges for the weapons.

According to Helton, the money was well spent.

"I think it's a deterrent, a lot of times. When [officers] go on scene and, say they're dealing with an individual that they've dealt with before, or who's familiar with the Taser, they see the bright yellow Taser sticking off the belt. Sometimes, it's that visual appearance alone. Because word gets out amongst the community, or people that have been Tased before say, 'Man, don't do it.' You see the Youtube videos or whatever else, and I think that has a lot of resonance," he said.

The decrease in use-of-force incidents coincides with two straight years of falling crime in Little Rock, according to police. Overall crime decreased 4.9 percent in 2014. Police data show it continued falling in 2015, though the final statistics were not yet available.

There were five complaints of excessive force last year, one of which the department upheld. Reports show the department did not receive an excessive force report during the final six months of 2015.

"I can tell you, by and large, when our officers use force it's because they were forced to," Buckner said. "Are there bad apples? You're always going to have your bad apples. But we're running a decent organization."

Metro on 03/16/2016