BEIRUT -- The Syrian government launched new airstrikes Saturday on insurgent-held neighborhoods in Aleppo while rebels shelled government-held parts of the northern city, as a truce in other parts of the country appeared to be holding on its first day.

Aleppo, Syria's largest city and former commercial center, has been the scene of intense shelling and air raids, killing nearly 250 civilians over nine days, according to the Britain-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

The surge in fighting has collapsed a two-month cease-fire brokered by the U.S. and Russia. It also has raised fears of an all-out government assault on Aleppo.

The International Committee of the Red Cross warned that the intensification of fighting threatens to cause a humanitarian disaster for millions of people. A statement issued late Friday said four medical facilities on both sides of the city were hit earlier that day, including a dialysis center and a cardiac hospital. The committee appealed to all parties in the conflict "for an immediate halt in the attacks."

"There can be no justification for these appalling acts of violence deliberately targeting hospitals and clinics, which are strictly prohibited under international humanitarian law," said Marianne Gasser, head of the committee in Syria. "People keep dying in these attacks. There is no safe place anymore in Aleppo."

"For the sake of people in Aleppo, we call for all to stop this indiscriminate violence," Gasser said.

Friday's attacks on the medical centers came after government airstrikes damaged a main hospital supported by Doctors Without Borders late Wednesday, killing more than 50 people, according to the international aid group.

Syrian opposition activists said Saturday's airstrikes on Aleppo killed four people and wounded many others, mostly in the neighborhood of Bab al-Nairab.

The Observatory and the Local Coordination Committees, another activist group, reported more than 20 air raids on rebel-held parts of the city, where an estimated 250,000 people remain.

State media outlets said rebel shelling of government-held parts of Aleppo killed one man and wounded others.

Aleppo-based activist Bahaa al-Halaby said warplanes and helicopter gunships are launching very "intense bombardments."

Another activist in the city, who spoke on condition of anonymity out of safety concerns, said schools have been ordered closed in rebel-held parts of Aleppo.

Aleppo was excluded from a brief truce declared Friday by the Syrian army. The truce went into effect early Saturday in the capital, Damascus, and its suburbs as well as the coastal province of Latakia. Activists said the truce appeared to be holding in both areas on Saturday.

Anas al-Abdeh, the head of the opposition Syrian National Coalition, told reporters in Turkey that Aleppo should not be excluded from the truce.

He added that his group has asked U.S. officials to contact Russia to make the government stop its operations in the northern city.

"The United States noticed that the regime is not abiding by the truce," al-Abdeh said, without elaborating.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry is leaving for Geneva today. He plans to hold meetings Monday with the U.N. envoy to Syria to discuss efforts to halt the violence and increase deliveries of humanitarian aid to besieged communities.

Kerry spoke Friday to Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov.

Government supporters say Aleppo should not be part of the truce brokered by the U.S. and Russia because al-Qaida's branch in Syria, known as the Nusra Front, is active there and in nearby areas.

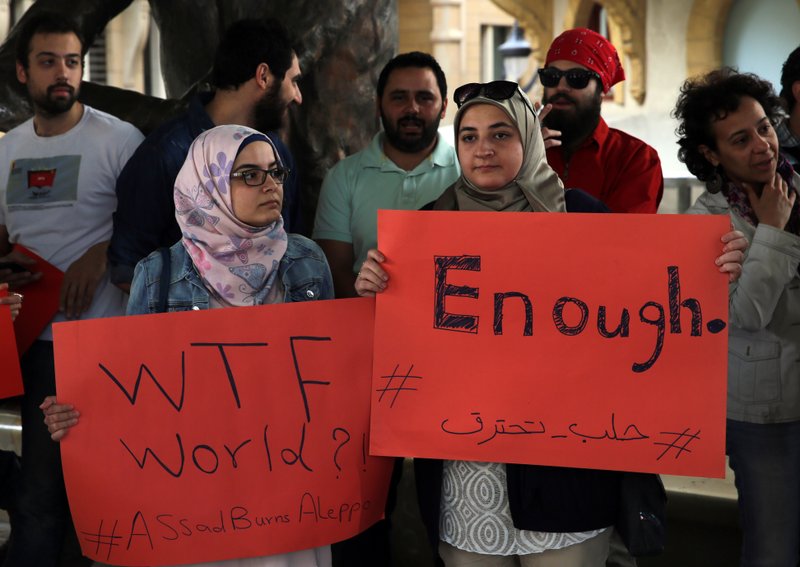

In neighboring Lebanon's capital, Beirut, more than 100 people marched in the city center to protest Syrian government attacks, mainly those on Aleppo, calling them "war crimes." Lebanon is split between supporters and opponents of the rebellion against Syrian President Bashar Assad.

In Damascus, International Committee of the Red Cross spokesman Pawel Krzysiek said that despite the difficult situation in Aleppo, which hinders humanitarian operations in the city, aid deliveries elsewhere continued. Humanitarian convoys entered areas besieged by rebels and government forces, he said.

The convoys, a joint operation of the committee, the United Nations and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, began delivering aid to Madaya and Zabadani -- two mountain resorts near Damascus besieged by government forces.

Krzysiek added that 20 other trucks entered the northwestern villages of Foua and Kfarya, which are besieged by insurgents.

The committee delivers food parcels and wheat flour, medicines, bed nets, crutches and anti-lice shampoo to all locations, he said.

The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs said on its Twitter account Saturday that the aid delivery in the four areas will be large enough for 61,000 people.

enemy nearby

One of the world's oldest inhabited cities, Aleppo has for centuries been known as the crossroads of empires, with Ottoman, Armenian, Jewish and French influences.

Today the only way in, on the government side, is a lonely road that cuts through hostile territory: a bumpy tarmac strip lined with deserted villages and isolated government outposts.

Like many war zones, other parts bustled with a semblance of normalcy. Traffic officers directed vehicles, laughing children poured out of schools and shoppers bustled through stores that sold food and artisanal perfumes. People seemed strangely immune to the background beat of explosions -- thuds, crashes and bangs -- that provide a deadly metronome to their daily existence.

That composed attitude, though, is seen as little more than a form of war-weary roulette. Whistling death, in the form of mortar rounds and rockets, can fall from the sky in any corner of the city at any time. In an upmarket restaurant, diners were jolted by the whoosh of a departing rocket, its engine thrumming for seconds before it launched, apparently from a nearby park.

The old city's sprawling medieval souk, or market, considered one of the Arab world's finest -- and a UNESCO World Heritage site -- is now a wasteland. Down a deserted street, a woman in fatigues sat in a bunker, boasting of how she once cared for tigers at the Aleppo zoo.

The woman, who goes by the name Rose Abu Jaffer, produced photos of herself being nuzzled by a lion, holding a python around her neck, standing beside a bear and allowing a tiger cub to press two paws against her head.

Her nine-year career as a zookeeper was cut short when the rebels occupied the zoo four years ago, prompting her to join the fight, she said. Now she is a front-line fighter.

The nearest rebel position was about 100 feet away, she said -- quiet for now, but unlikely to last.

"They only dare come out at night," she said. "They are like bats, cowardly bats."

Although Syria's revolt started as a protest against the authoritarian rule of Assad, whose family has ruled Syria for 46 years, it has stirred sectarian tensions and century-old historical grievances.

Most of the city's Armenian population, known for its goldsmiths, has fled to Europe or Canada. Many of those who remain are staunch supporters of Assad, whom they see as their only hope against Islamist fighters who would never let them live in peace.

Father Iskander Assad, a Greek Orthodox priest, lives in Maidan, a front-line neighborhood that is now half-deserted. A day earlier, a mortar round slammed into his home, punching a hole in the roof. His wife had been crying all night, he said, but he was not interested in sympathy.

"Sorry is no good," he said. "We need a solution. Sorry solves nothing."

On the edge of Aleppo's ancient citadel, Zahra and her family squatted in a once-grand apartment, now facing rebel lines. Plastic sheets covered its tall windows to shield the space from a sniper's view; shelling boomed in the distance.

Zahra, 25, who gave just one name, flicked between two photos on her phone. The first showed her husband, a Syrian army soldier and the father of her unborn child.

"Seven months," she said, touching her belly.

In the second, her husband was splayed on the ground, blood trickling from his nose. Two other fallen soldiers lay beside him. He died two weeks ago.

"May the men who did this also die," she said with quiet determination.

Information for this article was contributed by Bassem Mroue, Albert Aji and Matthew Lee of The Associated Press and by Declan Walsh of The New York Times.

A Section on 05/01/2016