SANKHU, Nepal -- As the anniversary of Nepal's devastating earthquake came and went last week, Tilakmananda Bajracharya peered up at the mountainside temple his family has tended for 13 generations, wondering how long it would remain upright.

The temple walls, which shook violently for more than a minute during the earthquake, are now split by fat, snaking cracks. Rescue workers braced the building's sides with wooden planks last year, said Bajracharya, the temple's priest, but they will snap as soon as the next large earthquake hits.

"Nothing will remain," he said. "We will live with the consequences."

Seeing the face of a foreigner last week, the priest brightened. Many people in the area pin their hopes on promises of foreign aid: After the disaster, images of collapsed temples and stoic villagers in a sea of rubble spread across the world, and donors, principally India and China, came forward with pledges of $4.1 billion in foreign grants and soft loans.

But those promises, so far, have not done much to speed the progress of Nepal's reconstruction effort. Outside Kathmandu, the capital, many towns and villages remain choked with rubble, as if the earthquake had happened yesterday. The government, hampered by red tape and political turmoil, has only begun to approve projects. Nearly all of the pledged funds remain in the hands of the donors, unused.

The delay is misery for the 770,000 households awaiting a promised subsidy to rebuild their homes. Because a seasonal stretch of bad weather begins in June, large-scale rebuilding is unlikely to begin before early 2017, consigning families to a second monsoon season and a second winter in leaky shelters made of zinc sheeting.

Veterans of immense relief efforts in Haiti and after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami say it is normal for spending to remain low for the first year after a disaster, then ramp up only after legislation and construction standards are in place. And since the earthquake, which killed almost 9,000 people, other problems have besieged Nepal, including violent protests over the passage of a new constitution and a blockade of fuel imports from India that lasted 4½ months.

Still, some visitors who arrived to assess the reconstruction expressed shock at how little had been done. In March, German lawmaker Dagmar Woehrl publicly warned Nepal's president that private donations to foundations and nongovernmental organizations would no longer be available if Nepal did not use the aid soon. She said it was the first time in her seven years as the head of parliament's economic development committee that she had given such a warning.

"I had the feeling that someone has to raise a voice and give an input from outside, because time is running out," Woehrl said in an interview. "It does not help a single Nepalese if there are millions of dollars of donation money on charity accounts. The money has to be invested now."

Others urged patience, saying the effort had shown signs of picking up steam.

"Compared to where we were six months ago," said Renaud Meyer, country director for the United Nations Development Program, "we've moved at thunderstorm lightning speed."

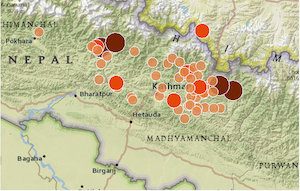

Sites like the ancient, battered town of Sankhu were a major reason foreign donors came forward so readily. Just before noon on April 25, the earthquake, with a magnitude of 7.8, sent century-old brick buildings crashing into the streets, crushing 45 people and destroying 1,200 homes. Centuries-old temples sacred to Hindus and Buddhists tumbled down the hillsides.

Bajracharya, the priest, recalled struggling to stay on his feet as the ground beneath the Bajrayogini Temple lurched violently, and then scrambling out of the complex to get clear of a storm of falling bricks.

"I myself surrendered," he said. "I concluded that I was not going to live."

Relief efforts kept pace during the weeks after the disaster, when half a million homeless families received about $140 in emergency aid. The goodwill reached Sankhu: By summertime, a foreign country had promised $570,000 to rebuild Bajrayogini and surrounding structures, said Christian Manhart, who represents UNESCO, the U.N. cultural heritage agency, in Nepal.

That early progress then halted. Leaders swung their attention to the fast-track adoption of the country's first constitution, and its division of power infuriated ethnic communities in the south. Bloody clashes between protesters and police ensued, and Indian border crossings shut down, leading to acute shortages of fuel and building supplies. Parliament did not pass a law creating the National Reconstruction Authority until December.

By then, friction had begun mounting between the government, which preferred foreign grants to be deposited directly into its budget, and donors, who complained of excessive red tape and often preferred to work through nongovernmental organizations. Until April, the government refused to allow international organizations to use their funds to begin building permanent housing, saying it wanted to control the standards.

"We are always dancing a little bit on the volcano," Manhart said of international donors. "We have the feeling we should assist the government in doing the reconstruction in a better way, but on the other side is inherited sensitivity not to intervene too much."

In January, Manhart said, the country that had promised to rebuild the Bajrayogini Temple informed UNESCO that the grant had been withdrawn because of budget cuts. He would not identify the country. A new benefactor has stepped in, he said, although the slow pace of work has tempered donors' enthusiasm.

A Section on 05/01/2016