WASHINGTON -- Poor, black and Hispanic children are becoming increasingly isolated from their affluent, white peers in the nation's public schools, according to federal data released Tuesday.

The data release coincided with the 62nd anniversary of the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated schools are "inherently unequal" and therefore unconstitutional.

That decision began the dismantling of the dual school systems -- one for white pupils, one for black pupils. It also became a touchstone for the ideal of public education as a great equalizer meant to give every child a fair shot at success.

But that ideal appears to be unraveling, according to Tuesday's report from the Government Accountability Office.

The number of high-poverty schools that serve primarily black and Hispanic students more than doubled between 2001 and 2014, the report found. The proportion of such schools -- where more than 75 percent of children receive free or reduced-price lunch, and more than 75 percent are black or Hispanic -- climbed from 9 percent to 16 percent during the same period.

The problem is not just that students are more isolated, according to the Government Accountability Office, but that minority-group students who are concentrated in high-poverty schools don't have the same access to opportunities as students in other schools.

"While much has changed in public education in the decades following this landmark decision [in Brown v. Board] and subsequent legislative action, research has shown that some of the most vexing issues affecting children and their access to educational excellence and opportunity today are inextricably linked to race and poverty," the report said.

High-poverty, majority-black and Hispanic schools were less likely to offer a full range of math and science courses than other schools, for example, and more likely to use expulsion and suspension as disciplinary tools, according to the report.

Courses on math, calculus and seventh- and eighth-grade algebra are seen as particularly lacking. In science, high-poverty schools had fewer biology, chemistry and physics courses than their more affluent counterparts with fewer minority-group students. Less than half of the mostly poor, mostly minority-group schools offered Advanced Placement math courses. Looking at all public schools, low-income and minority-group students were far less likely to enroll in these more rigorous courses.

Hispanic students at these schools tended to be "triple segregated by race, income and language," according to specialists and educators who were interviewed by the GAO.

The Government Accountability Office studied three school districts in the South, Northeast and West. Each took steps to increase racial and economic diversity in the schools but were hampered by transportation problems and obtaining support from the parents and the community.

In a separate paper, the Civil Rights Project at UCLA said New York and Illinois have been "at or very near the top of the list" of states where black and Hispanic students have been most severely segregated. It found that "residential resegregation" in some parts of Maryland spilled over into the schools and that in California, the percentage of Hispanics was increasing as the overall school population declined.

'overwhelming failure'

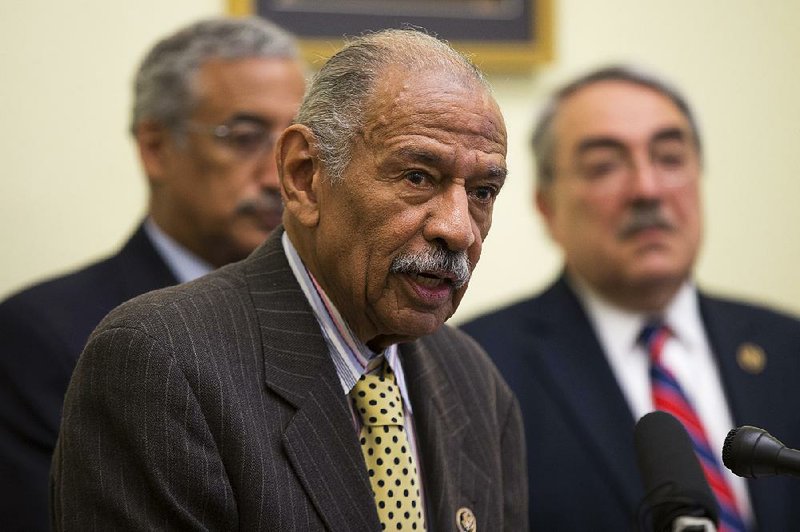

The GAO conducted its study during the past two years at the request of Democratic lawmakers including Rep. Bobby Scott of Virginia, the ranking Democrat on the House Education Committee, and Rep. John Conyers of Michigan, the ranking Democrat on the House Judiciary Committee.

Scott said the GAO report provided evidence of an "overwhelming failure to fulfill the promise of Brown."

"Segregation in public K12 schools isn't getting better; it's getting worse, and getting worse quickly, with more than 20 million students of color now attending racially and socioeconomically isolated public schools," he said in a statement Tuesday. "This report is a national call to action."

Along with the release of the report, Scott and other House Democrats are introducing legislation they say will "empower parents and communities to address -- through robust enforcement -- racial inequities in public education," according to a fact sheet from his office.

Education Secretary John King said one big reason for the disparities is money.

Inequitable resource distributions "are shaping inequitable opportunities for students," King said after the report was released. He said President Barack Obama has asked for more education dollars, including money for grant programs to support districts with community-developed plans that increase socioeconomic diversity in schools.

To combat the problem, the GAO recommended that the U.S. Department of Education step up its efforts to monitor the disparities among schools.

The Justice Department, the report recommended, could "track key information on open federal school desegregation cases to which it is a party to better inform monitoring." There are currently 178 open desegregation cases based on court orders from 30 or 40 years ago intended to integrate schools.

The Justice Department said the GAO's report had an "erroneous" understanding of the department's role in the desegregation cases and that the department already monitors each case.

In a response from the Education Department, Catherine Lhamon, assistant secretary for civil rights, wrote that King was trying to promote integration through grant programs.

"We are committed to using every tool at our disposal to ensure that all students have access to an excellent education," she wrote.

The resegregation of schools during the past two decades has for the most part happened quietly, in the shadows of standardized testing, teacher evaluations, charter schools and Common Core academic standards.

Segregation has returned to the forefront of education policy discussions only recently, in broad public debates about race, discrimination and widening inequality.

Advocates for desegregation as an essential tool for closing the nation's achievement gap have criticized the Obama administration for giving lip service to the issue without taking meaningful steps to address it.

Obama's current proposed budget includes a $120 million grant program meant to help communities diversify their schools, such as through magnet programs or dual-language classrooms that could draw middle-class families into high-poverty schools.

There are still plenty of challenges associated with such efforts. Officials in one urban district told the GAO that their popular magnet schools had to deny admission to some minority-group students in order to maintain diversity. And they poured so many resources into those schools that the traditional neighborhood schools -- which enrolled large concentrations of minority-group students -- suffered.

2016 desegregation order

The persistence of racial divisions in the nation's public schools was underscored Friday when a federal judge ordered a Mississippi district to integrate its middle and high schools, capping a legal battle that had dragged on for five decades.

As the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi put it, Cleveland, Miss. -- a city of 12,000 bisected by railroad tracks that divided white families from black -- has been running an illegal dual system for its children, failing year after year to reach the "greatest degree of desegregation possible."

Now Cleveland must consolidate its schools, integrating all its students into one middle school and one high school.

"The delay in desegregation has deprived generations of students of the constitutionally-guaranteed right of an integrated education," Judge Debra Brown wrote in her decision.

The Rev. Edward Duvall, who is black and has two children in Cleveland's public schools, said he favored consolidation because it would save money, leaving more funding for classrooms and programs. But that wasn't the only reason: "We can break down this wall of racism that divides us and keeps us separated," he said, according to court documents. "And we could create a new culture in our school system that's going to unite us and unite our whole city."

While schools in Cleveland have never fully desegregated, many other school districts did integrate after the decision in Brown v. Board. But since the 1990s, hundreds of school districts have been released from court-ordered desegregation plans, making way for renewed divisions by race and class.

In 1972, 25 percent of black students in the South attended the most segregated schools, in which more than 90 percent of students were members of minority groups, according to a 2014 ProPublica investigation. But in districts that emerged from court oversight between 1990 and 2011, more than half of students now attend such segregated schools, ProPublica found.

The investigation found fault with a Justice Department that, starting with President Ronald Reagan's administration, pulled back from pressuring districts on desegregation and was "no longer committed to fighting for the civil-rights aims it had once championed."

At the same time as federal courts were relinquishing oversight of school desegregation, the nation's overall student population was changing, becoming poorer and less white. More than half of students are now low-income, as measured by eligibility for subsidized meals. Hispanic students have replaced black students as the largest minority group in schools, accounting for 25 percent of the overall student population.

Information for this article was contributed by Emma Brown of The Washington Post; by Jennifer C. Kerr of The Associated Press; and by Joy Resmovits of the Los Angeles Times.

A Section on 05/18/2016