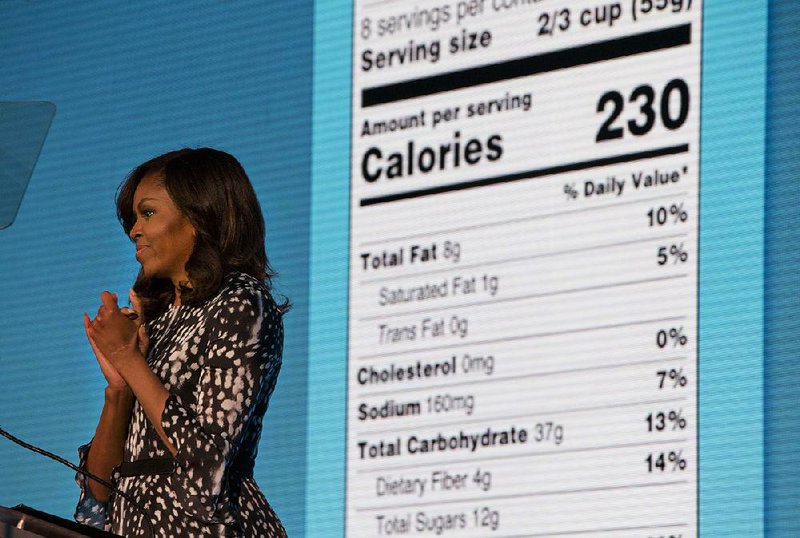

The Food and Drug Administration has created a new template for nutrition labels, which includes the addition of a line for "added sugar" to be placed below a line for total sugar.

First lady Michelle Obama unveiled the new label Friday, which represents major victories both for her legacy and the efforts of advocacy groups and scientists who have argued that the previous version made it difficult for consumers to assess the nutritional quality of any given food item.

"This is going to make a real difference in providing families across the country the information they need to make healthy choices," Obama said in a statement.

The change is designed to distinguish between sugars that are naturally occurring in a food -- such as the milk sugar in a plain yogurt -- and the sugars food manufacturers include later to boost flavors -- such as the "evaporated cane juice" in a Chobani Kids strawberry yogurt.

Critics of the policy argue that the difference between natural and added sugars is not nutritionally meaningful, and that the science establishing health harms from added sugar is weak. The new label will kick in for large food companies in 2018, and for smaller companies a year later.

The sugar industry argued that the label puts added sugar in an unfairly negative light, vilifying even small amounts.

"The Sugar Association is disappointed by the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) ruling to require an 'added sugars' declaration and daily reference value (DRV) on the Nutrition Facts Label (NFL)," the association said in a statement Friday morning. "The extraordinary contradictions and irregularities, as well as the lack of scientific justification in this rulemaking process are unprecedented for the FDA."

Not all food organizations, however, agreed. Both Mars and Nestle have supported the measure. The Grocery Manufacturers Association, a trade organization representing many large food and beverage companies, issued a statement calling the update "timely."

A team of researchers at the University of North Carolina conducted a detailed survey of the packaged foods and drinks purchased in U.S. grocery stores and found 60 percent of them include some form of added sugar. When they looked at every individual processed food in the store, 68 percent had added sugar. The list includes many sauces, soups, fruit juices and even meat products.

While some foods include "sugar" in their ingredients, many use different words for products that are nutritionally similar. Most have heard of high-fructose corn syrup, a sugar made from processing corn. But there are also things such as the "evaporated cane juice" in the yogurt, and "rice syrup" and "flo-malt," which are less obvious and amount to the same thing.

Barry Popkin, a professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina and one of the paper's authors, said the wide variety of sugars is not always meant to confound consumers. Instead, he said, the many sugar types are chosen by food scientists to give their products the best flavor and texture. Some sugars are better for baked goods, while others are better in soft drinks. Some are also cheaper than others. Sugar tariffs and import laws make it expensive to use foreign sugar. But not all of the sugar formulations count toward the laws' quotas.

There's also the matter of fruit juice concentrates, which are juices that have been stripped of nearly everything but sugar and evaporated. A lot of seemingly natural foods include ingredients like "apple juice concentrate." That's sugar. That will be a lot clearer when the labels are updated.

"It's going to really surprise people who go to organic and whole foods stores, when they find that all this natural food they've been buying is full of added sugar," Popkin said. "It's full of fruit juice concentrates, and they thought it was all good stuff."

The emphasis on added sugar comes from new nutrition guidelines that urge Americans to consume a "healthy dietary pattern" containing certain types of foods. According to the regulation, hidden added sugars make it difficult to understand whether some foods are part of that healthy pattern.

Medical evidence shows that high sugar consumption is linked to obesity, diabetes and tooth decay -- though not all of that work distinguishes between added sugar and total sugar.

The University of North Carolina research used its master list of sugar code words to measure how many grocery store foods include sugar. But measuring the precise amount of sugars that are added with the current label is difficult. Popkin said consumers would be surprised by recent research from his team revealing the large amounts of added sugars in products that are generally thought of as healthy -- foods like infant formula, protein bars and yogurt.

Information for this article was contributed by Roberto A. Ferdman of The Washington Post and by Margot Sanger-Katz of The New York Times.

A Section on 05/22/2016