Conway triathlete Erika Setzler has a goal.

Related story

In August, the 24-year-old personal trainer placed sixth at USA Triathlon's Olympic Distance Age Group National Championships in Omaha, Neb. This qualifies Setzler to compete for a world championship at the 2017 World Triathlon Grand Final in Rotterdam, Netherlands, and she wants to be prepared.

Little Rock cyclist Jason Macom, 35, also has a goal.

Macom, whose right leg was amputated below the knee in July 2015, wants to earn a spot on the U.S. Paralympic team and race his bicycle for a world championship on the track in 2017.

They both ended up at the Human Performance Laboratory of the University of Central Arkansas in Conway to take the kind of physical test that they hope will help them hit their respective targets.

Specifically, a metabolic test.

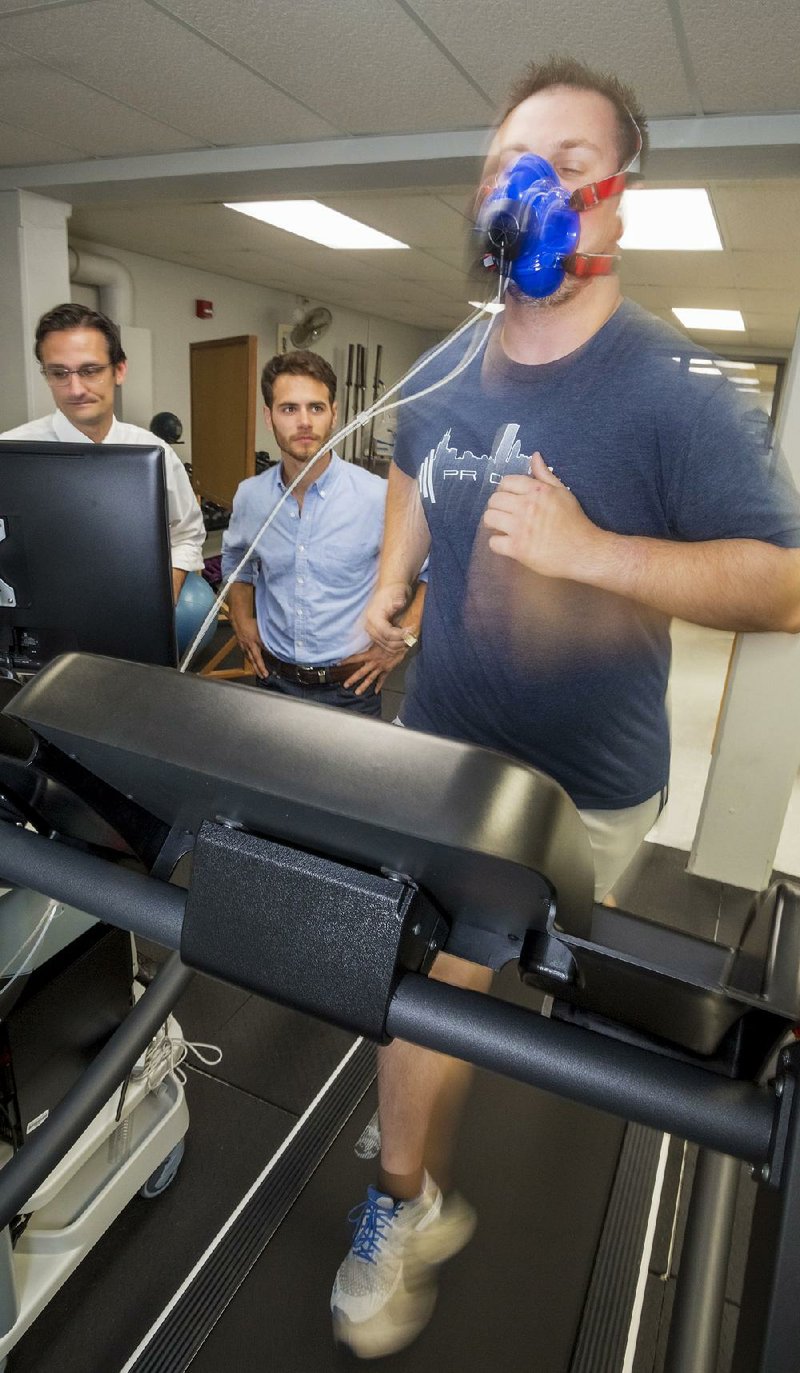

"Metabolic testing, commonly referred to as VO2 max testing, is where athletes come in and we put them through incremental exercise protocol," says UCA's Michael Gallagher, associate professor of exercise and sports science. "We go from a very low intensity in duration, usually two to three minutes, and then increase the intensity."

The test, which lasts from 12 to 20 minutes, is a grueling slog, with participants often left wiped out and ragged.

By the end, Gallagher will be able to suss out such data as the athlete's VO2 max, anaerobic threshold and how he utilizes fats and carbohydrates. All of this data can be applied by the athlete or a coach to construct a detailed training regimen.

Setzler, who is looking to improve in the cycling portion of triathlon, was tested in September. She brought her Quintana Roo time trial bicycle to the 1,200-square-foot lab in the Farris Center on the UCA campus. (Runners can take the same test on one of the lab's treadmills.)

Her bike was mounted to a stationary trainer and Setzler, a UCA graduate and former student of Gallagher's, wore a mask that measured her carbon dioxide output and that was connected to one of the lab's two metabolic measurement systems.

After a warm-up, she began pedaling as Gallagher gradually increased the resistance on her bike's rear wheel through the stationary trainer.

"My breathing was good, but my legs were very tired," Setzler says of her 20-minute ordeal. "It's like climbing up a hill, and I just couldn't go anymore."

At least it was free.

"Pro bono," says New Jersey native Gallagher when asked how much the test, which can run up to $200 in other labs, costs. "It's a service to the community. We also get students involved, and that provides extra experience for them in a testing environment."

Gallagher adds, though, that contributions to the UCA Foundation wouldn't be frowned upon.

"I give them the raw data," he says of what participants receive. "One thing I like about the test is that I get to help educate a little bit about what some of these values mean and why a coach might want that information. I love the education part, but I also really love the testing part."

HANDY DANDY DATA

The data gathered go a long way to help endurance athletes in training.

VO2 max -- the maximum volume of oxygen an athlete can use, measured in milliliters per kilogram of body weight per minute -- is "a good approximation of someone's health," Gallagher says. "Performance-wise, it helps provide more of a fine-training intensity."

For coach and pro cyclist Anna Sparks of Sparks Systems Coaching in Phoenix, who analyzed Setzler's and Macom's results, the VO2 max number suggests what her athletes have under the hood.

"Essentially what it's telling me is, what's the size of their engine?" says Sparks. "What does their overall physiology look like? Are they very aerobically efficient? Are they anaerobically efficient? Their VO2 will be the overall indicator of their fitness."

The higher the number, the bigger the output. For the general population, a number of "40 to 50 is usually going to be a good number," Gallagher says. "Not great, but an OK number."

Athletes will generally register a bit higher. Setzler, who ran track and cross-country at UCA, said her VO2 max was 62.6.

"It was a little lower than I thought it would be," she says. "[Sparks] said it was good for running, but we have some work to do on the bike."

RAISING THE BAR

Macom, who works at bicycle manufacturer Orbea in North Little Rock, had been away from competitive cycling for a while after breaking his ankle while playing bike polo. Lingering pain and disability eventually led to the amputation of his lower leg last year. His first bike race since his surgery was in February at a velodrome in Los Angeles.

He was hoping for a better mark on his VO2 test, "so there are things to improve on and look at," he says.

Athletes are almost always a bit disappointed in their VO2 results, Gallagher says.

"They've been training so long, they want to be here," he says, raising his hand above his head to indicate a higher level. "And then they're not quite there.

"They want to be in the 99th percentile, so when they get that number, they're always a little disappointed. Sometimes, they focus too much on it."

The number can be improved a bit, especially in younger athletes, Sparks says. Adults generally see incremental increases as they train harder and then take the test again. "We want them to go back to see if we see improvements," she says.

Some athletes undergo testing every three months or so, but that's overkill to Gallagher. Once in six to 12 months is ideal, he says.

TRAINING ZONES

Of course, the VO2 figure is just a part of the physiological insight provided by a metabolic test. Maximum heart rate, peak power, lactate threshold and the time it takes a runner or cyclist to reach fatigue can also be calculated.

Finding out when the body starts to use particular fuels by pinpointing the athlete's anaerobic threshold is also an important indicator of conditioning the test can reveal.

"When we're at rest or at low to moderate intensity, we're predominately using fats for our fuel," Gallagher says. "As our exercise intensity increases, so does the metabolic demand."

Run faster or pedal harder and eventually the body switches from using mostly fats to a mix of fats and carbohydrates and, finally, to mostly carbohydrates.

"If we know where that point is, we're able to match the heart rate up," to identify heart-rate training zones. If the athlete's heart rate is, say, 160 beats per minute before reaching anaerobic threshold, Gallagher says, he can train "at that intensity, give or take, to delay that fatigue."

"That's going to tell me the exact point in which they start utilizing energy from carbohydrates," says Sparks, a Fayetteville native and Ole Miss graduate who found out about the UCA Human Performance Lab when she worked for Little Rock-based Sigma Human Performance.

"I can put together a nutrition plan that will address the amount of calories these athletes need for an endurance workout, an intensity workout or when they're having a rest day."

"As soon as we start hitting that point where carbs become predominantly used, we're going to start fatiguing," Gallagher says.

A higher anaerobic threshold will mean that an athlete can train longer at high intensity before starting to wear out.

One of Macom's sponsors is Clean Eatery of Little Rock, a food-preparation and delivery service that specializes in restricted diets, including paleo, vegetarian, pescatarian, gluten free, vegan and paleo/vegan ("pegan"). "I'm working with their dietitian to dial in everything, as far as my lifestyle goes, around being a cyclist," says Macom, who missed out on competing in Rio de Janeiro with the 2016 U.S. Paralympic cycling team by one spot (they took 16 athletes; he was 17th).

"Metabolic testing can really help out in determining what types of fuels your body is burning at what heart rate. To have that knowledge, that hard data to go from, has really helped us modify my diet and has helped me eat right when I'm on the bike and off the bike as well."

For Setzler, the amount of data she got from the test was a pleasant surprise.

"They gave me a lot more information than I was expecting. I still have a lot of learning to do about what to do with that information, but I was very pleased."

Metabolic testing is also a good way to gain speed, says Macom.

"I would recommend it to any athlete serious about their performance. There are lots of easy ways to go about getting faster, and knowing what kind of fuel to put into your body and knowing what your heart rate zones are and what to do in those zones is easy information that you can do a lot with."

For information about testing in UCA's Human Performance Laboratory, call (501) 450-5000.

ActiveStyle on 11/21/2016