McNEIL -- By the time the emerald ash borer is done with its work, it will be remembered as a scourge right alongside the boll weevil, the army worm, Dutch elm disease and chestnut blight.

That's because, within a few years, the ash tree will be all but extinct in Arkansas and in other states infested by the beetle.

It doesn't take much of a walk into the woods of Logoly State Park in McNeil in Columbia County, a few miles north of Magnolia, for two forestry experts to find ash trees that are dead or dying.

Chandler Barton first points to the jagged holes left by woodpeckers that feast on the larvae of the emerald ash borer. "Woodpeckers do a great job, but there are just too many emerald ash borers," said Barton, a forest health expert for the Arkansas Forestry Commission.

A couple of whacks to the bark with a sharp hatchet reveals a labyrinth of trails, or galleries, left by tiny larvae as it feeds on a tree's nutrients for some nine months.

The tree is beyond saving, and it will be dead in a year or two, Barton said.

At another tree, Barton finds a D-shaped hole. It's the exit for the larva-turned-adult, which now will fly around for three months in a range of 1 to 3 miles, finding a mate and laying eggs on the bark of ash trees and then dying.

Once hatched, the larvae burrow under the bark, repeating the life stage -- one generation per year -- of the emerald ash borer.

The emerald ash borer is native to Asia. Its presence in the U.S. wasn't known until 2002, when it was found in Michigan, likely arriving there in packing crates from an overseas freighter. It has since spread to 30 states, where it has killed tens of millions of ash trees, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

Arkansas is home to five kinds of ash tree: Carolina, green, blue, white and pumpkin, with the thickest stands growing along river bottoms. All are at risk.

"No one can disagree that human transport is how it got to south Arkansas," Barton said, although spreading the beetle is unintentional.

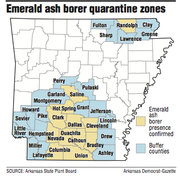

While officials have faint hope of fighting off the beetle entirely, they are serious about enforcing one element of their battle: limiting or, banning, the movement of wood outside a quarantined area where the beetle has been found and a buffer zone of adjacent counties.

It is illegal to transport certain items from within the quarantine zones to areas outside the zones. Quarantined items include firewood of any hardwood species, as well as ash tree products including nursery stock; green lumber with bark attached; living, dead, cut or fallen logs; pulpwood, stumps, roots, and branches; and mulch chips greater than 1 inch in diameter.

Barton said a quarantine, while difficult to enforce, is central in the efforts to manage the pests.

Barton said loggers and timber mills work together with the Forestry Commission in making sure beetle-infested ash doesn't get outside the quarantine zone but working with the public requires a willingness to learn.

Knighten Gunnels, a logger for 48 years and co-owner of Gunnels Mill outside Magnolia, joined Barton and a Forestry Commission co-worker, Jake Bodart, on the Logoly State Park trek. Gunnels said ash makes up only 1 percent of the wood he sees because his mill primarily produces crossties. "But I still see [emerald ash borer] damage every day on the ash that does come in," Gunnels said.

Gunnels asked if loggers could help by cutting infested ash trees and leaving them where they lay.

Barton said the effort was appreciated but useless: the larvae will continue to live inside a fallen tree.

Ash makes up only about 3 percent of the marketable hardwoods in Arkansas, so the economic losses aren't necessarily staggering, Barton said.

Still, the ash is popular in the making of furniture, baseball bats, guitars and boats. "But, ecologically, it is a disaster because we're essentially losing a whole genus of trees," he said.

Forestry officials are working on what they hope is a long-term solution -- introducing "bio-control wasps." The stingerless wasps have helped fight off the beetle in its native Asia, where ash trees are evolving to resist the devastation of the borer.

Some 4,000 of the wasps have been released in Arkansas, Barton said, and officials will know sometime next year how they fared.

While some insecticides have been known to work against the beetle, an insecticide is not practical in a forest where an infested tree has to be treated individually. A homeowner with a few ash trees should check with an extension agent for advice, Barton said, but he warned that damage is done from the top down.

By the time damage is found around the trunk of a tree, it's too late, he said.

Logoly, the first state park devoted to environmental education, got its odd name from combining the first two letters of the last names of three families who owned the land in the 1940s and refused to let its timber be cut: the Longinos, the Goodes and the Lyles. The emerald ash borer appears intent on doing at least some of the work that was denied loggers.

A Section on 11/26/2016