Art is not autobiography. It is not therapy or confession. We only think we can derive someone's story from what they once jotted down in a notebook, from their wishful projections and fantasies. Brian Wilson didn't surf. Bruce Springsteen didn't have a driver's license until he was in his 20s. Mick Jagger was no street-fightin' man.

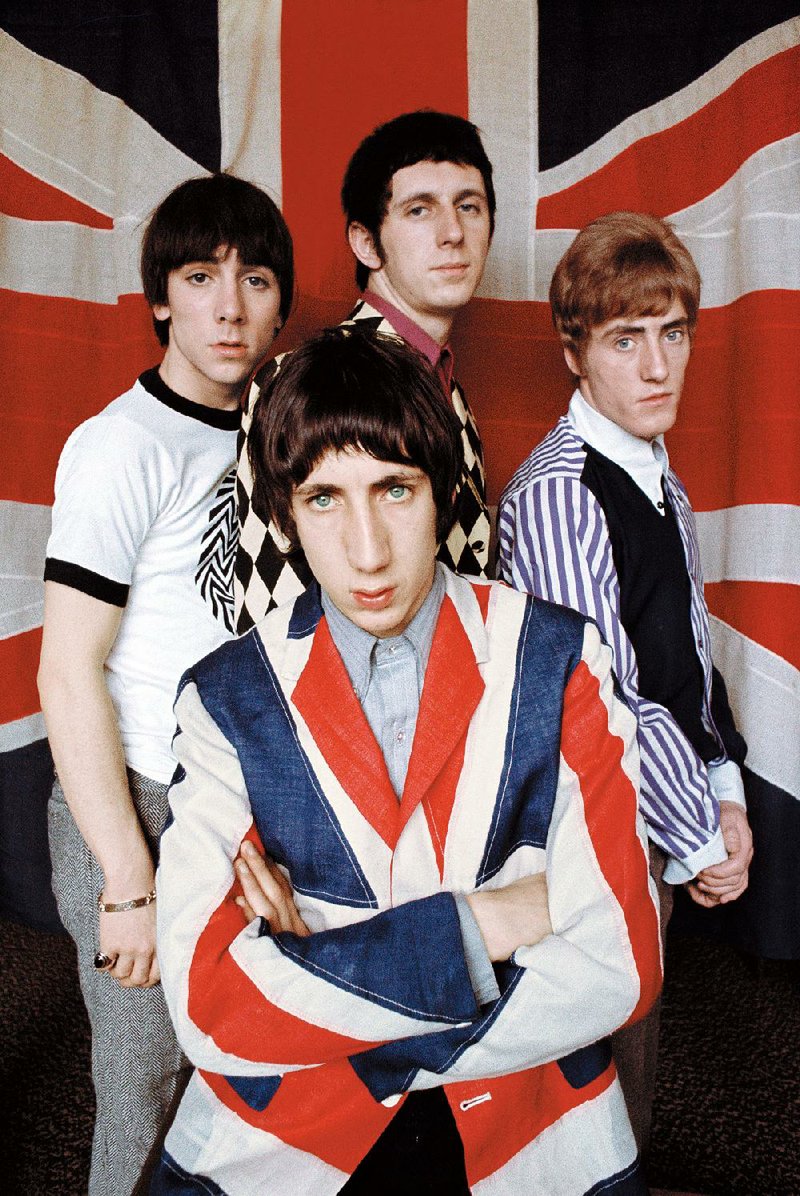

But Roger Daltrey was. There is a moment in the 2007 documentary Amazing Journey: The Story of The Who where a wizened older Daltrey -- in his 60s at the time of the interview -- sheepishly tells the film's co-director Paul Crowder, "I like to fight, I still do." That combativeness defined The Who as much as, maybe more than, Pete Townshend's songs, which were mainly written for the pugnacious front man.

The Who's first album, My Generation, was released in the United Kingdom in December 1965 and in the United States (as The Who Sing My Generation) in April 1966. The definitive British version was 36 minutes long. It was ferocious; an angry, petulant tour through the band's repertoire that crunched, snarled and chimed. It was probably the first mainstream album to react to the normalization of rock 'n' roll as pop. You could call it the first heavy metal record. You could call it the first punk record. Lots of smart people have.

It was also a rush job, quickly recorded (in about three hours, Townshend has said -- the band was well-rehearsed before entering the studio) and released, and The Who didn't think it fairly represented their live shows. They thought it too mild.

They would develop, getting smarter and some might argue more pretentious. They grew up, watched Keith Moon kill himself, presided over one of the great tragedies in rock history, grew apart, came back together. The great John Entwistle died. Daltrey and Townshend bickered on, sometimes collaborating. Sometimes releasing records, sometimes offering up annotated and curated deep dives into their history.

The just released five-CD "Super Deluxe Edition" of My Generation, timed to cash in on the 50th anniversary -- the $39.99 digital version is available now while a physical version that features an 80-page book and other extras will be available Dec. 9 with a list price of $189 -- of the seminal debut, is just such a deep dive. It's not essential, except to geeks who find satisfaction in hearing (and owning) new mixes of familiar tracks. There are more than 75 tunes here, none of which argue against the original judgments made by producer Shel Talmy.

But there's little point in pretending that anyone listens to an expensive, highly curated document like this simply to feel the shimmy of Townshend's guitar or the husky soul of Daltrey's voice (especially the adenoidal flattish drone on the minor mod anthem "The Good's Gone"). Most of the target audience will have lived with the original My Generation for decades, and while the title track -- with Entwistle's remarkable round-wound bass solo and Daltrey's stuttering vocal -- still commands attention, there's a sense that they've worn such a deep groove in the collective consciousness that it's impossible to hear them outside their historical context.

So, does it help to hear demos with the song's roots as Mose Allison-inspired blues? Yeah, it does, for it illuminates Townshend's magpie ear and the way that the artist's limitations shape the work. For even as Townshend was seeking to write songs for Daltrey to sing, it's clear that one of the biggest influences on Daltrey's vocals, especially in the band's early years, was Townshend's singing and phrasing. (Townshend is one songwriter who has never been shy about sharing his rawest demos, outtakes and home recordings -- see the various Scoop compilations he has released over the years.)

In some circles it has been fashionable to downplay Daltrey's role as something less than Townshend's, the band's chief songwriter and spokesman, who was naturally viewed as The Who's driving intelligence. Maybe a good comparison would be to Simon & Garfunkel -- while Artie is often dismissed as "just a singer," the truth is his very presence informs the duo's work. While the Townshend solo experience may be more trenchant and subtle than The Who's blitzkrieg bop, it isn't as gloriously bombastic.

...

Daltrey was indisputably the band's heart as well as its voice (while Entwistle and Moon were primal instrumentalists who redefined the capabilities of, respectively, bass and drums in a rock 'n' roll context). Daltrey incorporated Townshend's phrasing into his vocal style, but Daltrey owns an instrument of a different caliber -- a broadsword as opposed to a needle. The tension between these personalities has always contributed to the power of the band. Even Townshend's legendary dissatisfaction with the band -- he has been known to characterize his career with The Who as "a mistake" -- amplifies the unique nature of the partnership.

In Daltrey, Townshend found a kind of ideal working-class hero while he was, at the behest of the band's managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, squirreled away in upscale Belgravia, writing songs while living among upper-class twits and snobs. The story is that "My Generation" was inspired by Townshend's dilapidated hearse being towed from in front of his building, allegedly because Queen Elizabeth considered it an eyesore. Townshend, who had paid 90 pounds for the car, couldn't afford the 250 pounds it cost to get it out of impound, so he sold it to a fan and wrote the lyric, irritated at the boring old Queen who had nothing better to do than have teenagers' cars towed.

Townshend has written extensively about this period in his life, when his closest companions may have been two state-of-the-art Swiss Nagra recording decks that Lambert and Stamp -- whose day jobs had them working in film production -- had secured for him. Maybe the most illuminating new track on the set is a song that Townshend says he never offered the band because he couldn't imagine Daltrey singing it -- "The Girls I Could Have Had."

"I have often said about my early songs that I tried hard to appeal to Roger's sense of late teenage machismo," Townshend recently told London newspaper The Guardian. "Either that, or I attempted to sound like Jan & Dean so that Keith Moon -- who was a surf music fan -- would get behind the song. Here, a rather machismo and bragging song slipped away because it was more about me than Roger Daltrey, and certainly not a surf number. It's about my lack of success with girls when I lived at Chesham Place, partly because I spent all my time in my studio. Roger did very well with girls; it would never have worked for him to sing this lyric. The lyric is also fantastical. I make it sound as though I was turning down girls every day. In real life I was probably piqued that it rarely happened. My tape machine was my mistress."

While the song definitely qualifies as juvenilia, it boasts a walking country-derived bass line and a charming vocal by Townshend laced with a self-deprecating thread of irony:

Sit alone and shiver while the other guys are making,

I sit and think, sip a drink, try to roll one but I'm shaking,

Every day the same way, such a drag so bad

I might feel better then I'll just think about

The girls I could have had ...

If I'd a had the nerve

I could've had more chicks than I deserved

The other freshly turned-up demos -- the folky "My Own Love" and the dated "As Children We Grew" -- add relatively little to the picture aside from presaging the rootsier fork of Townshend's solo career and the hippie transcendence of Tommy.

While much of this material has surfaced on other collections, including previous anniversary editions of My Generation, the set is a great starting point for anyone interested in The Who's early days after they shifted away from the Daltrey-dominated High Numbers model.

...

No doubt it is a function of age to believe music matters less now than it did in 1965. But baby boomers are the great demographic bullies. Our music still holds a place of honor in the culture -- The Beatles, the Stones, The Kinks and The Who still exert a strange hold on us. Either you love this noise or you don't, and loving it means receiving it as is, taking all the gossip and mythology and rock critic exegesis you've ever read or heard as part and parcel of the game. It's OK to hold something dear because Robert Christgau or Lester Bangs pointed it out to you, just as it's OK to mishear lyrics and believe in whatever private idyll gets conjured in your head.

It's only rock 'n' roll.

My Generation really wasn't about my generation, it was about a generation that came of age in a post-war London, when the streets were filled with dead-eyed young men who'd seen the worst of what war can do. It nodded toward nihilism, it brought home the noise for a party for the end of the world.

And if we are intending to stay away from superlatives and hyperbole, let this be the exception to that capricious rule: the album also contains "The Kids Are Alright," a serious contender for the best rock 'n' roll song ever written.

Consider the lyric and the tune, Entwistle's clipped, frenetic bass, Moon's rats-on-a-tin-roof drumming, that ringing Rickenbacker D5 power chord that kicks it off, the message of solidarity, tolerance and patience: "I don't mind other guys dancing with my girl. That's fine, I know them all pretty well ..."

"The Kids Are Alright" isn't the standard rock 'n' roll posture and boast. It's an introspective song, a mope rock antecedent. The singer admits that he's got to get away from the party, that his tough-guy act is just a front.

Rock 'n' roll is all about that tough-guy act, that dangerous pose, but Townshend was one of the best at writing about the man inside the mask. A lot of early Who songs combine righteous anger with pure teenage petulance, and there's always a wrinkle in the words coming out of the singer's mouth.

Art isn't autobiography. But sometimes it is ventriloquism.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 11/27/2016