KINGSLAND — “Kickstart Kingsland,” a homegrown effort to lift commerce on the broad shoulders of native son Johnny Cash, is in search of a jump start.

Since the Missionary Baptist Church’s donation a year ago of a building that once housed a post office, the effort has stalled, said Mayor Charles Crain.

“We certainly want to have a museum or visitors center in there,” Crain said recently from a table inside the Citgo convenience store on U.S. 79, which skirts Kingsland’s northern edge. The former post office, just under 1,000 square feet, does have a new metal roof, Crain said, calling it a significant first step as the town of about 400 considers its next move.

A hundred yards down the street is a monument of sorts to Cash. It’s made of poured concrete, a couple of feet high, and a bronze plaque rests on a brick pillar. It is surrounded by a chain-link fence — “to keep the dogs out,” Crain said, acknowledging that the fence also somewhat obscures the tribute from passers-by. “You’d be surprised at the number of people who journey through here to take a look at that,” he said.

Cash was born about 3 miles north of Kingsland in 1932, near an intersection of gravel roads called the Crossroads community. His old homestead, never much to begin with, is long gone.

“I don’t remember living in that one, but I saw it once when I went to visit my grandfather,” Cash wrote. “It was a last resort. It didn’t have windows; in winter, my mother hung blankets or whatever she could find. With what little they had, my parents did a lot.”

“Kickstart Kingsland” is an offshoot of the larger “Kickstart Cleveland County.”

Each of four towns in the county — Kingsland, Woodlawn, New Edinburgh and the county seat of Rison — was charged with coming up with its own theme of revival and carrying it out, said Britt Talent, editor and publisher of the weekly Cleveland County Herald and a founder of the countywide campaign.

“Of the four, Kingsland might be the best situated,” Talent said. “You’d be shocked how many people from around the world go into that small town, but there’s nothing there really dedicated to Johnny Cash.”

What does Kingsland need for its “kickstart”?

“Kingsland has the physical means to do what they’re wanting to do,” Talent said. “It needs that concerted effort of everybody in town being on board. Kingsland is very small and limited in its financial means, but everybody knows that success in Kingsland will drive traffic throughout Cleveland County.”

Donald and Donna Sims live on the property where a young J.R. Cash babbled and crawled, then learned to walk. A few peach trees mark the spot.

The Simses are accustomed to the occasional visitors whose extra sleuthing in town takes them to their place. They do not mind the interruptions and understand the attraction, Donna Sims said, inviting a reporter to take a look and a walk around. “We’re just country people,” she said.

Sims said the town deserves a boost, whether brought on by Cash or by other chapters in the piney woods’ rich history along the Saline River bottoms. She and others point out, rather kindly, that Paul “Bear” Bryant, the famed football coach at the University of Alabama, was born in Moro Bottom in Cleveland County, not in Fordyce in Dallas County, a few miles to the west.

“There wasn’t much out there for anyone to try to save” once Cash became famous, Crain said, explaining that’s why he thinks the people of Kingsland don’t begrudge the attention — and hundreds of thousands of dollars — ladled on Dyess in Mississippi County, where the Cash family moved in 1935, when little J.R. Cash was just 3.

Arkansas State University and a series of Cash musical tributes have helped raise money to restore Cash’s boyhood home, as well as a couple of key buildings, in what was then called the Dyess colony, an effort by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to give destitute Depression-era farmers a second chance.

But for someone who spent so little time in a place, Cash never forgot Kingsland.

“Outside of Kingsland, he was Johnny Cash, but here he was just J.R.,” said a cousin, Mark Rivers, whose mother, Evelyn, helped Carrie Cash deliver Johnny. Born in 1952, Rivers is 20 years younger than his famous cousin, who died in 2003.

Most of Cash’s trips were out of the public eye, Rivers, 63, said. “He came here to fish, maybe hunt, but mainly, he loved to sit and talk,” he said. “Most folks never knew he was here.”

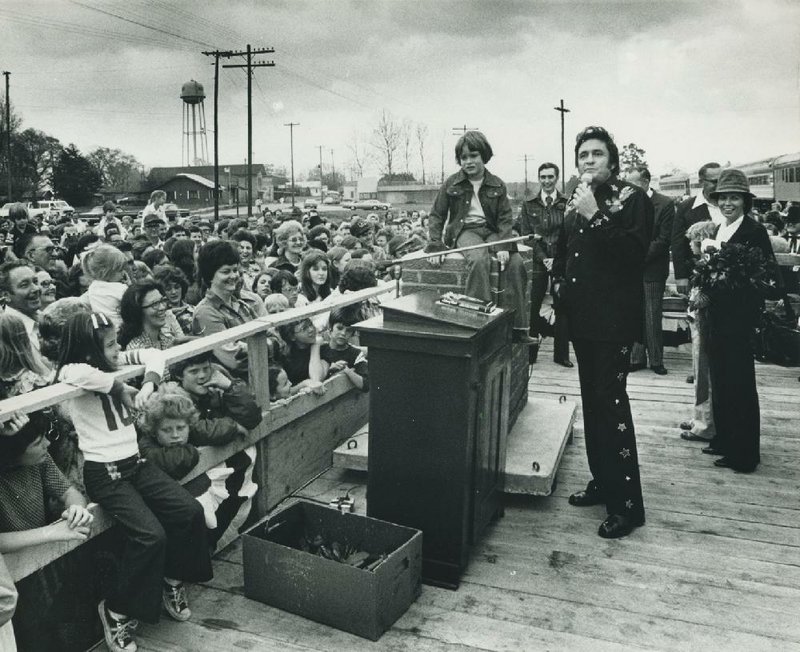

When Cash made public appearances, they were big.

In 1994, he returned to Kingsland to dedicate a new post office, which replaced the one now being sought as a museum. About 5,000 people showed up for that.

But his biggest show with the biggest bang came in 1976, when some 12,000 people turned out in Kingsland and Rison for a Johnny Cash concert and parade. Cash rode into Rison from Kingsland on a seven-car specially commissioned Johnny Cash Bicentennial Special, from the Southern Pacific-Cotton Belt railroads.

Both homecomings are commemorated, through photographs and newspaper clippings, behind glass at the Kingsland post office. But regular business hours for a post office in Kingsland are 8 to 11 a.m.

Rivers and others say they hope ASU can do a little for Kingsland of what it did for Dyess. Rivers said Cash’s only son, John Carter Cash, has offered his help. Memorabilia and merchandise still remaining from the House of Cash, which housed a museum as well as Cash’s publishing company in Hendersonville, Tenn., could find its way to Kingsland, Rivers said.

“If we can hire one or two people at the new museum, it will help more than just those one or two people,” Rivers said. “As much as it will be about Johnny Cash, we also want it to be about the people in his songs — people who work so hard to eke out a living and try to do the best they can.”