Ninety-three years the good old Broadway Bridge carried all comers across the Arkansas River, but not us, not today.

All that river-crossing Arkansans used to do so merrily, merrily? Over. Find another route. Wait our turn.

As we count life's many flaws, a true story from the past would help to pass the time.

"How about the one about the time an airplane landed on the bridge?" Helpful Reader suggests.

Why, thank you, Reader. Here's that story from the Sept. 22, 1948, Arkansas Gazette.

Landing On Bridge May Yield 'Cure' For Drunks

"Any drunks near the Broadway Bridge just prior to dawn this morning probably got a 'quick cure' if J.O. Dockery of the Kenneth Starnes Aviation Service landed on the bridge as scheduled in a Cessna 170 airplane.

"While the inebriates might have 'sworn off' at the unusual sight, the pilot knew the bridge gave him more room than necessary. It is 40 feet wide and 2,240 feet long. Rated landing distance for the plane with a full load (which it was not to have carried) over a 50-foot obstacle is 1,580 feet.

"Mr. Starnes plans to exhibit the plane at the Civitan Trade Show at the Auditorium Thursday through Saturday. Flying it in will save some dismantling and hauling. The landing was to be made only if wind and visibility conditions were ideal.

"Sheriff Tom Gulley, whose Junior Deputy Sheriffs League will receive 65 per cent of proceeds from the trade show, assisted in making arrangements for the landing. Permission was obtained from the state Highway Department, State Police, Little Rock and North Little Rock police and the Civil Aeronautics Authority."

JUST A DOGGONE MINUTE

Were conditions right? Did Dockery land on the bridge?

Arkansans born during the past 42 years won't believe public safety monitors would ever have let a pilot try, because of the big arch on top of the deck. It would complicate the stunt considerably.

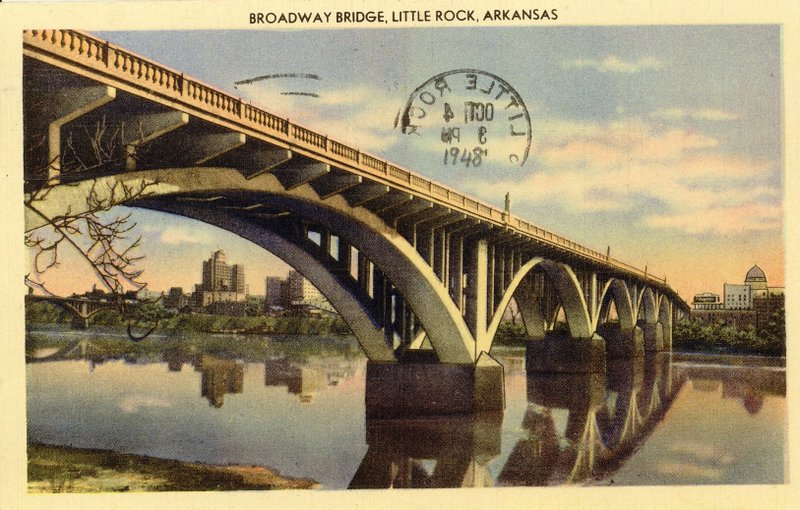

But it didn't exist in 1948.

Broadway Bridge's original, open-spandrel design had no above-deck arch when the bridge opened in March 1923. Instead it rested on five arches, all below the deck. As Noel Oman reported for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette in 2011, two of those arches were removed in 1974 and that upper arch added to take up their load, widening the navigation channel.

Oman also explained what spandrels are and the difference between closed and open ones, but I'm not going to. We need a little mystery in our lives.

WHAT DO WE KNOW?

From ads placed in the 1948 Gazette by the Civitan Club and its sponsors, we know the Cessna was to be displayed at an expo at Robinson Auditorium; admission would be free; and the three-day agenda included live music and vaudeville acts as well as door prizes. Attendees might win a $175 radio console combination, a standard make 7.5-cubic-foot electric refrigerator or hams, hosiery, kitchen gadgets ....

The next day's newspaper did not bother to report whether the airplane landed intact, but it didn't report a fiery inferno, either.

But 27 years later, Charles Allbright (1929-2015) interviewed Dockery in a four-part series of his column The Arkansas Traveler. In part one, the pilot confirmed he stuck to that bridge landing.

It was a new Cessna, Allbright wrote, and Dockery set it down at 6 a.m. "The aircraft had a wingspan of 38 feet. He had pre-measured the width of the bridge at 42 feet."

Quoting Dockery: "That was no stunt, just precision flying. ... The landing was no sweat because there was no wind. I just had to be careful to land short because the bridge is crowned. They towed the Cessna into the Auditorium."

It wasn't the most exciting thing Jess Orval Dockery had ever done. Far from it.

Once he set down in the Arkansas River, at night, and by luck touched down on a sandbar. Twice, he crashed while crop dusting, and in one of those crashes found himself hanging in the air outside his plummeting plane.

He was a member of "the Caterpillar Club," having been forced to use a parachute.

WHAT A LIFE

Dockery "flew literally in the dawn patrol of aviation," Allbright wrote. "Having no charts and radios, he followed rivers and railroad tracks. He night landed in fields marked off by two smudge pots, judging his speed by the whistle of wind in the wires."

He learned to fly from a World War I pilot when he was a 6-foot-tall, 120-pound 12-year-old. "The idea of fear never came near me," he said.

By 17 he had a pilot's license signed by Orville Wright. He barnstormed with Charles Lindbergh and lied about his age to get the bond required to deliver mail, on the second air-mail route, ever. He was already a flight instructor and his many students included Wiley Post, who became the first pilot to fly solo around the world.

"You can't officially say I taught him because I was too young," Dockery told Allbright. "What happened was, I flew with Wiley, out in Oklahoma, until he learned to fly. Then I got out and the man who owned the airplane got in and took Wiley up and said he was ready to fly."

Post died with humorist Will Rogers in an airplane crash in 1935.

When Dockery died in Florida in December 1997, in bed and 88 years old, his obituary was picked up by The Associated Press. He "helped perfect the science of crop dusting," the AP said.

In 1924 during an outbreak of armyworms, teenage Dockery and another pilot sprayed calcium arsenate -- poison -- and in a nod toward self-preservation, the teens figured out how to keep it out of the cockpit.

"During World War II," the AP said, "he served briefly in the Army, teaching pilots how to fly fully loaded bombers because of his experience with heavily laden crop dusting planes. The Army discharged him because his crop dusting business was considered more vital to the war effort."

In Stuttgart, he founded and ran a crop dusting service with a fleet of up to 60 aircraft. After the 1960s, he got out of crop dusting and worked as a tour pilot and flight instructor.

"There is no doubt in my mind, absolutely none," he said, "the most dangerous time in a pilot's life is when he gets into his car to drive to the airport."

There you have it, folks. Cars are dangerous. It's good to drive slowly. Think about that as you wait in line to cross the river.

Next week: Frightened Mule Is Cause Of Mishaps

ActiveStyle on 10/03/2016