In the early 1800s, passenger pigeons were the most common birds on Earth, numbering in the billions. They were beautiful, streamlined creatures with slate-blue heads and wine-colored breasts, as large as crows and incredibly swift and graceful flyers. They nested from the Canadian provinces to Kansas, Kentucky and New York, and wintered in several Southern states, including Arkansas.

The stories told about the once vast numbers of these pigeons seem almost unbelievable today.

In 1813, for example, while making a 55-mile trip from his home to Louisville, Kentucky, John James Audubon watched an immense flock of passenger pigeons crossing the Ohio

River. He was curious how many birds there might be.

“Feeling an inclination to count the flocks that might pass within the reach of my eye in one hour,” he wrote, “I dismounted, seated myself on an eminence and began to mark with my pencil, making a dot for every flock that passed. In a short time, finding the task which I had undertaken impracticable, as the birds poured in countless multitudes, I rose, and counting the dots then put down, found that 163 had been made in 21 minutes. I traveled on, and still met more the farther I proceeded. The air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse, the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow; and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose.”

Audubon concluded that from the time he left home until he arrived in Louisville, no less than 1.115 billion birds had crossed the river, and that such a flock would require

8.712 million bushels of food per day. And this was only a small part of the flock that took three full days to pass.

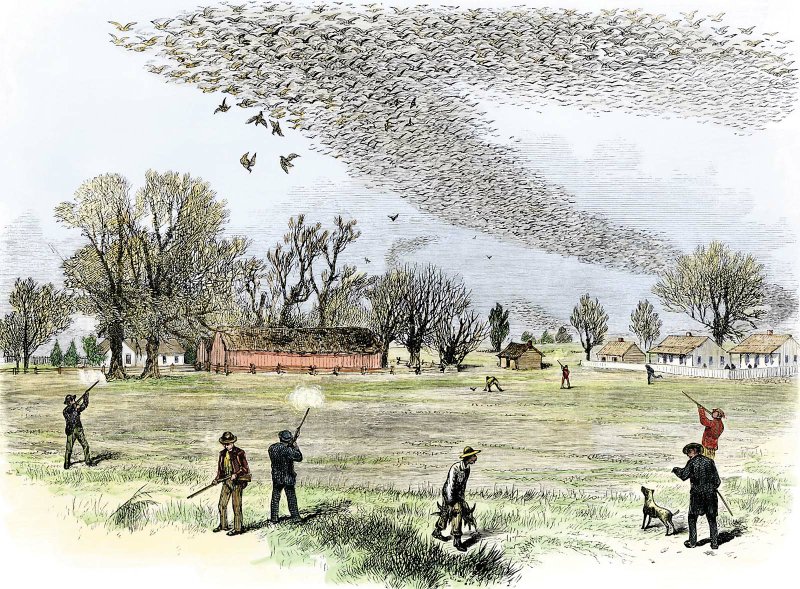

In A Natural History of American Birds, published in 1925, ornithologist E.H. Forbush wrote of the passenger pigeon, “Vast multitudes, rising strata upon strata, covered the darkened sky and hid the sun, while the roar of their myriad wings might be likened to that of a hurricane; and thus they passed for hours or days together, while the people in the country over which the legions winged their way kept up a fusillade from every point of vantage. Where the lower flights passed close over high hilltops, people were stationed with oars, poles, shingles and other weapons to knock down the swarming birds, and the whole countryside was fed on pigeons until the people were surfeited.”

Arkansas was one of the places where pigeons were hunted relentlessly. The Arkansas Gazette reported on Oct. 27, 1841, that two men went out to the Fourche Bar just below Little Rock and “killed 900

pigeons with 15 shots.” The Aug. 22, 1915, edition of the Gazette had a story that reported the enormous disappointment the boys of Little Rock had when an enormous rain in August 1859 “delayed the arrival of wild pigeons which flew over the town morning and evening in flocks of hundreds of thousands. With double- and single-barrel shotguns, parties of boys would station themselves at various points of advantage in the town, fire simultaneously into the flocks as they passed over, bringing down hundreds of birds. The principal roosting place of the pigeons was in that part of Prairie County, near Brownsville, now a part of Lonoke County. They roosted in the trees, and at night, the commercial hunters slew them with clubs, bringing them into Little Rock by the wagon load.”

At times the pigeons were destructive, taking a heavy toll on crops. The Arkansas Intelligencer

in Van Buren reported on June 21, 1845, “The wild pigeons this year accumulated about Jackson in this State, laid, and hatched out their young, and from a correspondent we learn are destroying the wheat crop to an alarming extent.”

By this time, many passenger pigeons were being taken by market hunters who shipped them to St. Louis, New Orleans, Chicago, New York and other large cities where they sold for 1 or 2 cents each. Some professional hunters and netters made hundreds, even thousands, of dollars a day killing the birds for market.

It wasn’t long before these “pigeoners,” as they were called, could keep one another informed of their quarry’s movements. Aided by the development of the telegraph system and a spreading network of railroads, the pigeoner could arrive promptly wherever pigeons gathered to roost or nest, and send back to the markets many tons of the dead bodies of these beautiful birds. The pigeons’ meat was delicious and cheap, and their by-products — feathers, blood, viscera, even dung — were used in the treatment of human ills by those gullible enough to believe the labels on patent medicines. Even live birds were sold, to be used as living targets by trap shooters.

This large-scale commercial destruction of the pigeons began in the 1840s and reached its highest point late in the 1860s. Billions of passenger pigeons were killed annually during this period, but whenever someone suggested laws were needed to conserve the bird, the cry at once went up that the pigeons needed no protection, for their numbers and the extent of the country over which they ranged were both so large that protection was unwarranted.

Let us jump forward now to March 24, 1900. It is a cool day near Sargents, Ohio. While feeding the family cows, 14-year-old Press Southworth notices a strange bird eating corn in the barnyard. He returns home and persuades his mother to let him take the 12-gauge shotgun and shoot the bird.

“I found the bird perched high in the tree and brought it down without much damage to its appearance,” Southworth wrote 68 years later at the age of 82. “When I took it to the house, Mother exclaimed, ‘It’s a passenger pigeon!’”

His mother is correct. This is, indeed, a passenger pigeon, a fact confirmed 10 years later when the bird’s mounted body, which had been placed in an Ohio museum, was examined. Reports of sightings continued for years, but no other wild-passenger-pigeon reports could be authenticated after young Southworth killed that single bird.

Attempts were made to save the pigeon, but it was too late. The only passenger pigeons that remained were captive birds — two males and a female in the Cincinnati Zoo. In April 1909, one male died. On July 10, 1910, the second male, then very frail, also died. With the death of that bird, any remote hope of ever breeding more passenger pigeons died, too.

The single remaining bird, a female named Martha, lived four more years to the ripe old age of 29. At 12:45 p.m. on Sept. 1, 1914, she trembled. Her head sagged. Then Martha dropped very quietly from her perch and lay dead.

With Martha’s death, the passenger pigeon — a bird that once numbered in the billions, a bird that once darkened the heavens as it passed — ceased to exist. That such an enormous population of any living creature could have been wiped out in such a short time is beyond belief, yet it is true.

It is a story that bears repeating every now and then so it will never happen again.