On Aug. 6, 1991, Tim Berners-Lee posted to a newsgroup with the subject heading "WorldWideWeb: Summary," describing his new invention in the most prosaic of terms. "To follow a link, a reader clicks with a mouse," he wrote. "To search and index, a reader gives keywords."

The Web browser that accompanied this launch was text-only. Two years later, Mosaic became the first browser to display images inline--that is, right next to the text, rather than having to be downloaded in a separate window.

Berners-Lee was displeased. Now, he said, people were going to start posting

pictures of naked women.

He wasn't wrong.

The World Wide Web recently turned 25. For most of the years since it came online, its destiny and evolution have been inextricably intertwined with nude photos. The sexualized female body has, from the beginning, been the catalyst for attempts to regulate what's on the Web, ultimately shaping what the Internet looks like today.

Only a couple of years after Berners-Lee began to worry about an incoming flood of photos of nude women, Congress was gripped by the "great Internet sex panic of 1995."

"The information superhighway should not become a red-light district," then-Sen. James Exon (D-Nebraska), said on the

floor as he introduced the Communications Decency Act. He would later read a prayer into the Congressional Record decrying the dangers of online pornography.

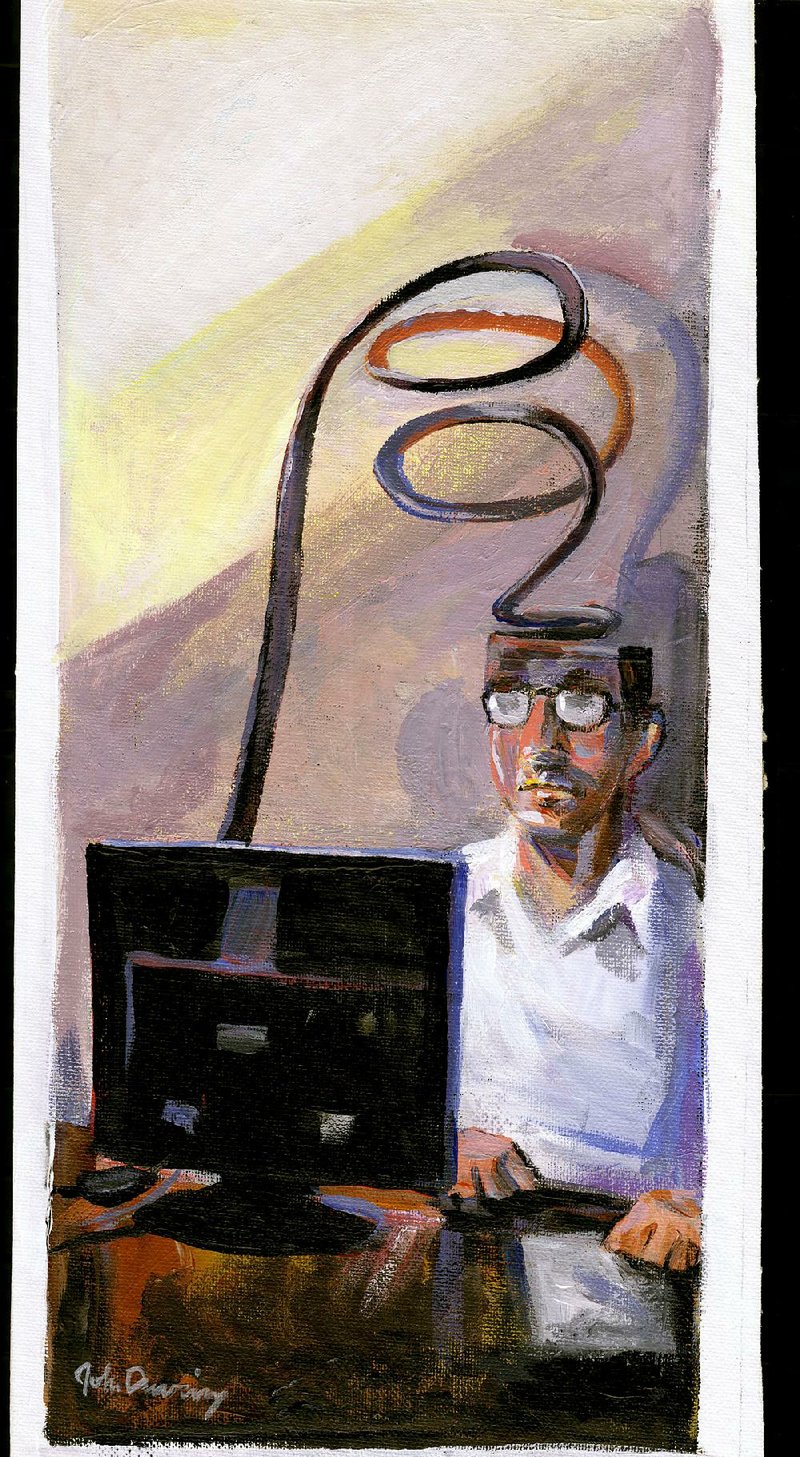

He wasn't the only one alarmed: On July 3, 1995, Time ran a cover story about the menace of "cyberporn," illustrated with a close-up of a wide-eyed, baby-faced kid staring into the cold glow of a computer screen. The story was based on a study claiming that not only were the bulk of images on the Internet pornographic, but online pornography tended to be more "deviant"--it was mostly BDSM, bestiality, even child porn.

The study, which was not peer-reviewed, was largely bogus. The Web took note. "Hell hath no fury like an Internet scorned," wrote the New York Times. But Internet outrage wasn't quite as intimidating then as it is today, and the great sex panic carried on. The CDA was signed into law on Feb. 8, 1996, and thousands of websites went dark in protest.

The act had a lot of parts, but at its heart were provisions that criminalized sending or displaying to a minor "any comment, request, suggestion, proposal, image, or other communications" that were sexual in a "patently offensive" way. The law sought to "zone" cyberporn away from children by requiring stringent age verification via a credit card or an "adult verification number," a password that supposedly only adults would have. But what was cyberporn, anyway? The law's authors were clearly terrified of the effects of naked women on children, but "cyberporn" isn't a legal term of art. Did the obscene include a discussion thread about Lady Chatterley's Lover? Did it include a museum website advertising a Robert Mapplethorpe exhibit?

Indeed, a year later, the Supreme Court determined that these provisions were unconstitutionally vague and struck them down for violating the First Amendment. Reno v. ACLU marked the first time the Supreme Court addressed the Internet, and the court felt the need to include 1,000 words just describing what it was, marveling at its capabilities ("two or more individuals wishing to communicate more immediately can enter a chat room to engage in real time dialogue") and widespread use ("at any given time 'tens of thousands of users are engaging in conversations on a huge range of subjects' ").

Tens of thousands is nothing by today's standards; Facebook alone estimates that it has more than 1 billion daily users. But we could have never gotten to today without Reno v. ACLU, which protected tiny startups and future Web giants alike from the stringent requirements and criminal liability provisions Congress first tried to put on the Internet.

Yet another part of the widely loathed CDA--one the Supreme Court has never heard any challenges to--also helped bring about the Web we now know. Section 230 immunizes service providers from lawsuits over the speech of their users. It's the law that lets Facebook, YouTube, WordPress, Twitter, Yelp, Craigslist and Reddit exist. Without its provisions, a service such as Twitter could be sued into nonexistence if an individual user sent a single defamatory tweet.

In 2011, Congress geared up for another round of regulating the Web. But this time lawmakers wanted to wash their hands of the '90s-era sex panic. As the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) gained momentum, Rep. Jared Polis (D-Colorado), who opposed the bill, introduced a pornography-focused amendment that would prevent the Justice Department from using the bill's copyright enforcement powers on behalf of the adult entertainment industry. Polis even took the opportunity to put the lyrics of "The Internet Is for Porn" (a song from the musical Avenue Q and a popular Internet meme) in the same Congressional Record that 15 years earlier had anti-porn prayers read into it.

His amendment was defeated, but in a way that marked a huge change from the gleeful porn-bashing of the Communications Decency Act era. Legislators shied away from the debate, with many quietly skipping out on the vote. Ultimately SOPA was defeated as well: In an uncanny and unintentional callback to the CDA blackout protests, sites such as Wikipedia and Reddit went dark on Jan. 18, 2012, and the whole country sat up and noticed. Within a few days, the bill was doomed.

The Web was different now. The Supreme Court had once marveled at how "tens of thousands of users" could be chatting at any given time. Now users in the millions were screaming angrily at Congress. The outrage in the wake of the CDA had been trifling; the outrage over SOPA couldn't be ignored.

We're still in the grips of panic over pictures of naked women. But the intervening years have changed how we perceive the naked body. Berners-Lee saw nude women as a distracting nuisance that would clog up his beloved text-only invention. Exon thought of pictures as the victimizers and Web surfers as the victims. These days we've moved from seeing images as digital objects to seeing the people inside the photographs.

This shift is exemplified by the twin controversies surrounding "revenge porn" and nipple censorship. In response to popular demand, many major social-media sites have chosen to censor nonconsensually published nude photographs, popularly known as revenge porn.

At the same time, Instagram and Facebook have been under fire for censoring deliberately, consensually posted photographs that show women's nipples. Activists have photoshopped male nipples on top of female breasts to mock the gender inequality--and old-fashioned prurience--at the heart of the rules. They're sometimes the very same folks who lobby for censorship of revenge porn. It's not an inconsistent stance: Rather than measuring the value or offensiveness of a photograph by how people might respond to it, they've chosen to focus on the consent of the subject.

When hackers posted nude photos of celebrities on Reddit in 2014, the controversy focused less on any inherent sexuality in the photos and more on the violation the subjects felt. Actor Jennifer Lawrence, whose photos were part of the hack, called what happened to her "a sex crime."

As it happens, it was the '90s-vintage Communications Decency Act's Section 230 that protected Reddit from most forms of legal liability. (The site did eventually take down its section that aggregated the photographs, possibly because of media criticism.)

Section 230 is now under attack for enabling the exploitation of women. High-profile litigation has attempted to eviscerate it for allegedly protecting sex traffickers, and an anti-revenge-porn bill was recently introduced in Congress. (Lobbying by the tech industry, much stronger and more politically active than in the 1990s, helped keep the bill from targeting Section 230 directly.)

As the Web turns 25, it's worth looking back on how the Internet has changed our perception of the naked female body and the woman who is the naked body. All attempts at Internet regulation raise the same question: What is the ideal level of responsibility for the companies, platforms and websites that make up the Web? It's not a coincidence that female nudity is so frequently the catalyst for these policy battles. Our convoluted, twisted and ever-evolving social attitudes about sexuality create a perfect flash point for issues of censorship and responsibility.

Pictures of naked women aren't done changing the world because our views on pictures of naked women aren't done changing. From the ongoing conversation about campus rape to the debate on sex work, we are still hashing out thorny questions of agency and victimhood. The next 25 years of Internet regulation will reflect that journey. From the moment the Mosaic browser started displaying pictures to users, this was the Web's inevitable fate: to march in lockstep with naked women.

Editorial on 09/04/2016