After a fire in April 2015 destroyed the wooden Italianate Victorian home Jennifer Carman was restoring, she was crushed. But this spring brought a new love -- an even bigger Italianate, this one brick, just blocks from her now-vacant lot.

The 38-year-old Little Rock resident's latest restoration project is the Mills-Davis house -- a rambling 18-room, 4,060 square-foot, once-majestic but now-weathered and deteriorating mansion looming large at 523 E. Sixth St. in the MacArthur Park historic district of Little Rock.

Skeptics may wonder, does Carman have bats in her belfry?

Well ... yes and no.

Yes, she has bats; about 200 big brown ones. In her attic. There used to be more but the summer heat drove some to move on their own.

And no, her house doesn't have a belfry. But it was originally crowned with a cupola, which she hopes to reconstruct.

It's a labor of love for Carman, who lives in Little Rock's Central High neighborhood where she and her friend and business partner Donna Thomas have restored 13 historic houses.

Like the Mandlebaum-Pfeifer house, which she lost in the fire, she plans to house her art advisory and appraisal services business J. Carman Inc. Fine Art in the Mills-Davis house once it is restored.

"It's technically still zoned as residential but I will apply for a zoning variance to operate a quiet business."

A community project

Carman knows the house is interesting to many. She has established a Facebook page for the new project, which currently has 189 likes. In May, before work began, she held an open house for the public. It lasted four hours and drew more than 200 people.

"I've always believed the house, in some way, belongs to each of us who have ever driven past and slowed down to admire it," she says.

Carman first encountered the house when she lived in a nearby apartment after graduate school.

"I knew it was a house that was beloved to everybody. It has always felt to me to be one of those houses."

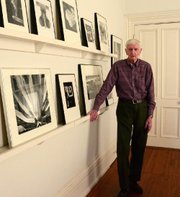

Bill Davis, the previous owner and longtime commercial photographer turned fine art photographer, died on Feb. 13 at 96. He was a widower following the death in 2011 of his wife, Jody.

As an appraiser, Carman says she was familiar with Davis' work. Carman attended his estate sale and bought a painting. "At the sale," she says, "I half-jokingly asked, 'Is the house for sale?'"

Later, she learned the estate's executor was exploring discreet options for sale. Davis had owned and lived in the home for nearly 70 years and wanted to see it preserved by someone who would have a personal stake in the property -- possibly as a single-family home. Davis' father bought the house for his son in 1945 with the paychecks Davis sent home while serving overseas in the U.S. Navy during World War II. The decorated war veteran came home to a house he owned but hadn't seen or chosen to buy.

"It gave him angst at the time and he would later mention it to me more than once," says executor Joan DuBois, 78, a longtime friend of Davis and his wife. "He would say, 'Can you believe someone would do that!?' He had mixed emotions about the house, but grew to love it."

The couple had no children and no heirs. A portion of the proceeds from their estate went to the Arkansas Arts Center and nearly all of his 1,000 photographs were distributed to several institutions including the Arts Center, the Historic Arkansas Museum, the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, DuBois says.

Carman bought the house, which was never publicly listed, this past spring for $84,000.

"I will be putting $350,000 to $400,000 into it," she says. She intends to use federal historic preservation tax incentives to support the restoration.

"Without those tax credits, projects like this would not be feasible."

The credits require renovations to meet strict guidelines for authenticity. A rough estimate from Little Rock architect Tommy Jameson to rebuild the cupola ranges from $40,000 to $50,000.

"I would like to think it's closer to $40,000," he says. "But that's a very ornate little jewel box that was once up there."

A tale of two styles

Some decisions regarding the restoration are clear for Carman. The house, currently divided into several apartments, will stay divided to accommodate Carman's appraisal business and an apartment.

Her plans for interior design, however, are not as well formulated. The house was built in Italianate style in the late 1870s or early 1880s but its original owner, Judge Abraham "Anderson" Mills and his wife, Eliza "Eudie" LeFevre Mills, who owned it until the 1940s, remodeled the house in the late 1800s or early 1900s in that era's popular Colonial Revival style.

She believes the house's exterior, which is painted dark green, was originally a soft red brick, but a photo from 1903 suggests it was painted a neutral gray/ocher with white trim and dark green or black shutters.

"I'm leaning toward gently cleaning the surface and letting the brick continue to weather."

Carman believes that for most of the house's early life, its interior walls were adorned with wallpaper.

"The house has Italianate roots but has been transformed with Colonial Revival elements," she says, referring to the massive staircase, newel post, and its four quarter-sawn oak fireplace mantels.

Which leaves her at a decorative crossroads.

"There's such a sense of pressure to do the right thing and that means different things to different people," says Carman, who has a master's degree in decorative arts.

"I might be tempted to go the whole nine yards with the textiles and furniture of the Aesthetic movement," she says, referring to the decorative elements of the house's original style.

She has learned, however, that the Davises preferred the midcentury Modern aesthetic movement, and that has made her feel more relaxed about design choices.

"Ten years ago I was a purist and would have tried to bring it into a museum, but I think I will probably have furniture from all different time periods," she says.

"The people who've been here before me made such thoughtful decisions," she says, noting how a pair of floor-to-ceiling bookcases in the front parlor were painstakingly designed to fit around and not damage the front parlor's decorative baseboards.

"I heard that the original newel post is in the attic but I'm doubtful," Carman says, noting that she has not yet fully explored the uppermost level because of the bats. She has only been up there long enough to find a six-gallon crock, an empty suitcase, a larger screen for her nearly 5-foot-wide front door, and the remnants of the cupola. Which brings us back to her uninvited squatters, the likes of which have been hanging around upstairs for the better part of a century.

Batty for bats

She has taken care not to disturb the maternity colony of big brown bats during their spring and summer birthing season, delaying roof work until after the juveniles have matured. Measuring up to 5 inches long with a wingspan of up to 13 inches, her uninvited guests can reach flight speeds of up to 40 mph.

For abatement, normally, a one-way exit is put in place but her house has too many entry points. The good news? Her renovation work will probably save her the $15,000 removal fee she was quoted.

"Since I'm replacing the roof and also the bat guano-soaked attic floor and second-floor ceiling, I'll spend just $600 on the backyard bat house my dad is building."

Carman hopes the bats move out of the attic but stick around.

"They can eat 1,000 mosquitoes a night and are really an asset."

Unexpected costs

Soon after Carman bought the house, a thief cut out a small section of exposed copper pipe and, in doing so, damaged a water line underneath the house. And since the house also has a well and cistern, there was no accumulating water to alert her. Instead, her next water bill did. It was $2,200.

She repaired the water line for $2,000 and Central Arkansas Water reduced her bill to $1,200. In addition, she has spent about $4,000 for architectural plans for the reproduction cupola.

"So $7,000 has been spent and there's not much to show for it yet," she says. In addition to securing the house from bats, her plans include repairing the house's interior, adding central heat and air, replacing the roof, and repairing damaged exterior woodwork.

Her to-do list

So far, the only work that has been done is light demolition, mostly of badly damaged bat guano-soaked plaster ceilings and unwanted additions such as dropped ceilings and a closet under the staircase. In areas where plaster fell, Davis, even in his later years, attempted to patch it himself, climbing a tall ladder and stapling white photo paper to the ceiling.

A ladder resting on the roof has been there at least since 2003, when Carman first noticed it while strolling through the neighborhood. As recently as spring 2015, Davis was still climbing up onto the roof to clean out his gutters, his friend DuBois said.

"I want to rehab it in a sensible way and at this point, it needs everything," Carman says. She obtained a work permit from the city and is acting as her own contractor. She'll be doing much of the work -- light carpentry, tiling, floor refinishing, re-glazing windows, stenciling or wallpapering -- herself. She has no concrete timeline for completion.

"It'll be done when it's done," she says, laughing. "But I hope it will be sometime next year."

Enlightenment from a darkroom

"I have felt lots of ambivalence about changing or dismantling Bill Davis' darkroom or the turn-of-the-century bathroom," Carman says.

"The preservationist in me feels that part of the house's charm is leaving everything exactly how it is -- like a time capsule of sorts -- but then another part of me knows that time marches on and that we must march with it. I suppose that in the end I'll have to feel at peace with the notion that Anderson and Eudie Mills or Bill and Jody Davis would probably approve (at least in spirit) of the choices I've made in rehabilitating the house."

HomeStyle on 09/17/2016