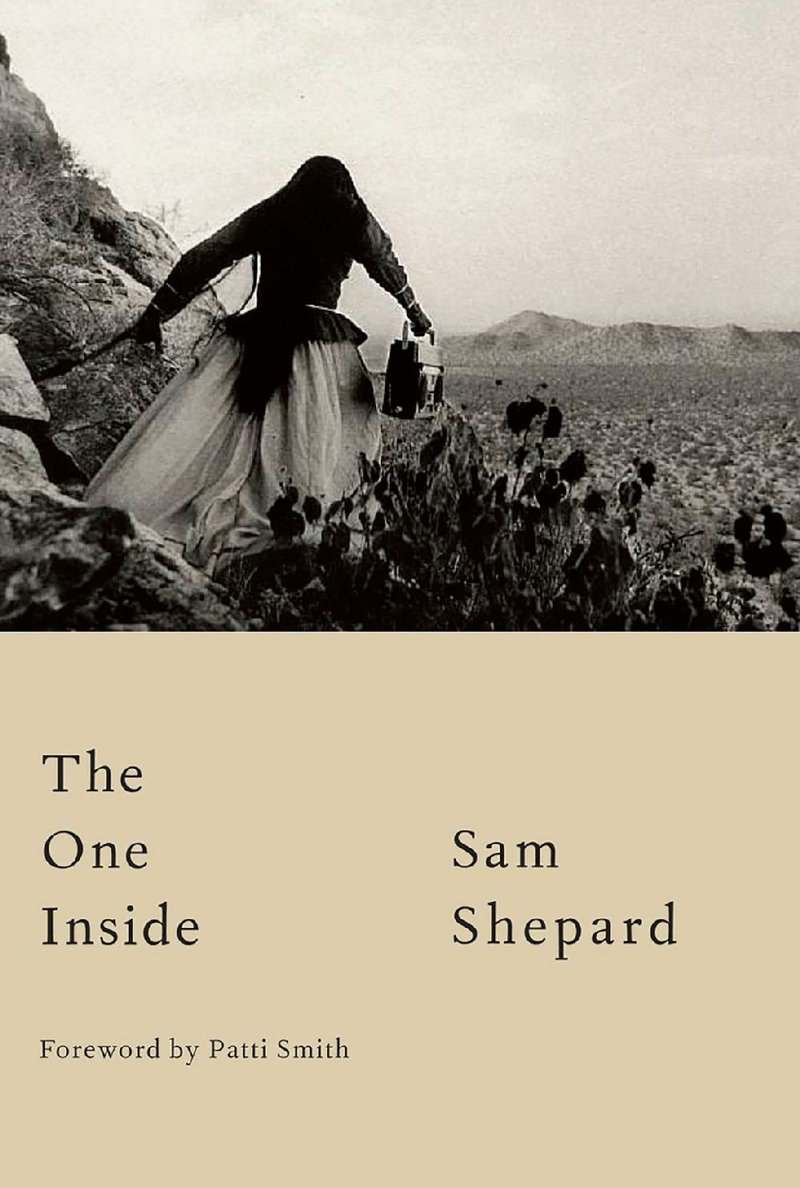

Sam Shepard calls his new book The One Inside (Knopf, $25.95) a novel. Patti Smith, in her foreword, calls it "a coalescing atlas, marked by the boot heels of one who instinctively tramps, with open eyes, the stretches of its unearthly roads."

There, I've set up a joke for us. So what do we call it?

Well, let me resist throwing out a punch line. Because while The One Inside lacks the sort of narrative drive that usually attaches to a story -- there's no resolution and possibly no point, just the detached and grim observations of a man we might assume to be Shepard himself -- it is a powerful thing, no matter what you call it. Reading it in bed with my wife beside me I told her I really liked it, but couldn't imagine anyone else putting up with it for long.

That might be its genius or at least its gimmick. Reading the The One Inside feels like hearing a friend's confession. You feel privileged; the confessor flatters you by assuming your empathy, your adult understanding of the way serious-minded people (men) live in the world. Of course there are young women, semi-vampiric and doomed with their "incredulous green eyes" and the loyal wife of 30 years, now an ex but friendly, who understands you well enough to keep clear. They can love you in whatever ways they can muster, but in the end they can't compete with the other within, the one inside. Ziggy Stardust called it making love to your ego.

I'm a sucker for this sort of masculine self-examination; this way of presenting your smart self as dumbly male, surrounded by the accoutrements and accessories of the wild boy intellectual: battered Tacoma pickups, near feral dogs and D.H. Lawrence's Mornings in Mexico. Competence with tools, incompetence with electronic and digital technologies. Roadside cafe breakfasts and DVD-bingeing Breaking Bad. Graham Greene novels and the inexorable, disgusted withdrawal from modern frivolity.

It was a trope when Hemingway tried it on. Shepard has embodied it as a playwright and an actor but even more so as one of those seemingly reluctant but surprisingly durable celebrities. Shepard turns up in places you might not expect him -- classing up popular entertainments (like Jeff Nichols' Mud and the Netflix series Bloodline) while engaging in outre sonic experiments with T Bone Burnett and writing -- with the furious ambition of a 17-year-old who has just discovered Rimbaud and Verlaine -- this fractured, tender book. He's everywhere, yet invisible. Ask him what he's written, he'll tell you tersely, "Words."

So The One Inside is not for everyone, maybe not for many. But there's a truth in the dead father dreams that Shepard writes about, something solid shrouded by the incoherence. There are mountains behind the clouds that you sense more than see. They don't move and, for all your indomitable will, when you meet them it's you who will yield. For like the song says, you're just a man.

...

Rodney Crowell has been through it, man. I remember when he blew through here back in 1989, when he told my former colleague at Spectrum Weekly Jim Nichols how they used to back the cocaine truck up to the house he shared with his then-wife Rosanne Cash in Nashville. Crowell was a co-conspirator on Cash's remarkable '80s albums and, before that, as part of Emmylou Harris' Hot Band in the '70s, he essentially saved country music. Crowell had a period of commercial grace in the late 1980s, but for the past 25 years or so has pursued a career as one of those literate Americana stalwarts -- a songwriter's songwriter, the prime time-ready version of Guy Clark or Billy Joe Shaver.

That said, his albums have been hit or miss propositions these past few years; 2001's The Houston Kid is a minor classic and 2003's Fate's Right Hand had a few transcendent moments -- "Still Learning How to Fly" ranks among the best songs he has ever written. But the more topical The Outsider (2005) had some filler between the high points and the best thing about 2008's Sex & Gasoline was its title, despite the efforts of producer Joe Henry. 2013's Old Yellow Moon, his duet album with Harris, was a burnished exercise in nostalgia and the best thing to be said about his experiment with memoirist/novelist Mary Karr (2011's Kin) is that it was an earnest effort to merge the ultra-specific, confessional mode of a self-aware literatist with honky-tonk heroism. Crowell has been consistently interesting, but he sometimes produces compelling failures.

While his new album, Close Ties, doesn't feel particularly adventurous, it's a solid 10-song tour of Crowell's personal mythology and would serve the uninitiated as a good entry point. Produced by Jordan Lehning and Kim Buie, it feels almost like a compilation record, collecting the sort of autobiographical impressions that informed The Houston Kid and Crowell's 2011 memory book Chinaberry Sidewalks.

Crowell's difficult childhood and partially misspent youth impinges upon his work in the mournful "Reckless" and the delicate piano ballad "Forgive Me Annabelle," while the album's centerpiece, "Life Without Susanna," remembers the formidable songwriter wife of Crowell's hero Guy Clark (who wrote the title track of his 2013 album My Favorite Picture of You about her).

Both Clarks are gone now -- Susanna died in 2012, Guy last year -- and one imagines that Crowell, at 66, feels mortality bearing down. Which goes a long way to explaining the album's closing track "Nashville 1972," an unabashedly backward-looking roll call of the luminaries -- including the Clarks and Steve Earle -- who've played a part in Crowell's sentimental education. It's wistful near-schmaltz that coming from another artist might feel like a humble brag.

The other highlight is "It Ain't Over Yet," a mature and tender song that features Cash and John Paul White. It's a warm and affecting coming to terms that encapsulates Crowell's problematic charm. Yes, he's smart. Yes, he's deep. Yes, he deserves credit as one of the progenitors of Americana. But he's probably better when he's not so concerned with impressing us with his erudition and taste.

...

We started watching the Canadian sci-fi series Continuum on Netflix for the laziest of reasons; it is set in Vancouver and we like the city. I mistook Rachel Nichols, the American star of the series, for Rachel Griffiths, an Australian who was in the HBO series Six Feet Under (and was nominated for an Academy Award for Hilary and Jackie back in 1998). Turns out Nichols is about a decade younger than Griffiths, and, while unknown to us, a veteran of American TV.

We're just into season two of the show's four-season run (it was on the Canadian cable channel Showcase from 2012-2015 and later on the Syfy channel) because it is completely and utterly mad. It has something of the flavor of one of those live-action adventure series that used to occasionally pop up in between Saturday morning cartoons in the early '70s. While it's definitely not designed for kids, it might be designed for kids who affectionately recall Shazam! and The Secrets of Isis.

The setup is relatively simple: In the future, eight convicted terrorists escape execution by exploding a device that hurls them 65 years back to 2012. Police officer Kiera Cameron (Nichols), sensing something fishy just before the explosion, rushes in to stop it and is also thrown back in time.

There she soon meets Vancouver police officer Carlos (Victor Webster, splitting the difference between a young George Clooney and David Bazzel), and serendipitously connects with a teenage technical wizard who will grow up to be a sort of Bill Gatesian techno-political messiah -- the most powerful figure on 2077's earth.

The show is about Cameron and company's attempts to thwart the terrorists' attempts to monkey-wrench the ultra-clean corporate dystopia that's coming. (Which suggests that maybe the terrorists, though bloodthirsty and cruel, maybe aren't the bad guys.) Meanwhile, Cameron's main objective is to get back to her husband and child in 2077, though things are becoming more complicated as we get deeper into the series.

The main reason we watch is for the camp value. The special effects are standard, the acting is in a hammy key that admits woodenness and scene-chewing and the writing is bizarre. So far the writers haven't wasted a whole lot of time worrying about the implications and potential paradoxes of time travel (though when a character's grandmother is killed he isn't immediately erased, to his own surprise) but having glanced at the series' Wikipedia entry I realize that's about to change.

Is it worth the couple of hours or so a week we're investing in it? That's hard to say, although it's enjoyable enough on a number of levels -- sophisticated users are likely to perceive it as something along the lines of a poorer, less brutal The Blacklist. It's not the sort of television that compels attention -- a long way from the Twilight Zone-ish Black Mirror or even a run-of-the-mill British police procedural -- but it can serve as a nice nightcap.

...

Arcadia Publishing and History Press is a South Carolina-based company that publishes local and regional history books, often working with authors obsessed with arcane subjects that are of limited interest to people outside of circumscribed geographical areas. What's great about a lot of these books is how deeply they delve; when you get a good one it's like extracting a core sample from a strange and wonderful culture.

Michael Hibblen, a familiar voice heard regularly on public radio station KUAR-FM, 89.1, has produced one of the good ones. His Rock Island Railroad in Arkansas ($21.95), to be published Monday, collects more than 150 captioned photographs, plus design plans, ads and short chapter headings that trace the 80-year history of the passenger and freight railroad in Arkansas. (The bankrupt railroad was shut down by a judge in 1980.)

While a few reminders -- most notably the pedestrian and cycling bridge over the Arkansas River that forms the eastern boundary of the Arkansas River Trail and links the Clinton Presidential Center grounds to North Little Rock -- remain, most of the tracks have been torn up, leaving the state with a few stray depots and little other evidence of the once vital line where the streamlined Choctaw Rocket shuttled back and forth between Memphis and Amarillo, Texas.

Hibblen's book is the product of deep affection and meticulous research. Browsing through a copy of the book, it's difficult to say which is more apparent.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 04/02/2017