When the original Trainspotting hit theaters back in 1996 (yes, it has been that long -- let's all take a collective sigh), it dropped like a cultural atom bomb, with the fallout and reverberations felt through to the next wave of Euro-filmmakers. Utilizing a hyperactive, quick-cutting, anything-goes style, the film, about four friends in Edinburgh shooting dope, running roughshod over the city, and scheming to a big score, put Iggy Pop's "Lust for Life" into mainstream culture, helped make a star of the film's lead, Ewan McGregor, and propelled director Danny Boyle -- whose only previous feature, Shallow Grave, was well received but little else -- to a status of young Turk.

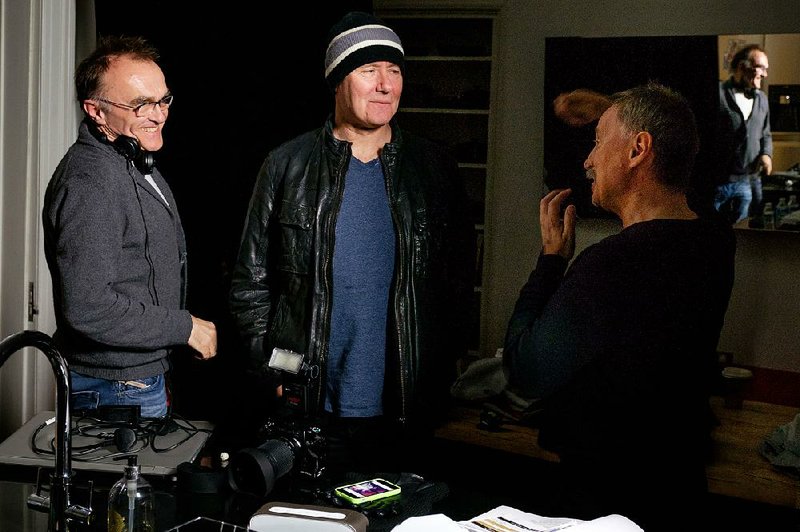

He hasn't wasted the opportunity, producing an oeuvre containing the interesting (Sunshine, Trance), the brilliant (28 Days Later...), and the Oscar-winning (Slumdog Millionaire). T2 Trainspotting, the follow-up to his biggest cult hit, comes a full two decades after the original, a very conscious decision on the part of the director and his longtime screenwriting partner, John Hodge. We are reunited with the boys, now middle-aged men, mostly unhappy, largely unfulfilled, and sinking into a morass of mediocrity. The director spoke with us about the danger of sequels, the TV show that influenced him, and Robert Carlyle's shocking transformation.

Q. Most distant sequels spin their wheels trying to re-create the dynamism that made the original so popular, but this film seems to go a completely different route, embracing the middle age the characters are mired in. Is that why you waited so long to revisit this world?

A. We tried to do it 10 years ago and it was a caper, so it was exactly what you described. It just felt what it was, a caper. But then when we got really serious a couple of years ago, it was clear that you had to make it about time. What does time mean to you? I have to admit, in retrospect, I think [screenwriter] John Hodge and I were not prepared or honest enough 10 years ago to admit to some of the stuff that's in this. I think that gives it its poignancy and honesty.

Q. Honesty is really important in a film like this, where so many people so deeply connected to the characters in the original.

A. There's nothing wrong with that. People like being [humored] sometimes. It's fine for a mainstream film, but in the case of this, something very precious because of its original reputation, if you're going to return to it, you do want to do it honestly, even if that means that some people think it's not as exciting as the first movie, which it clearly isn't. You can't pretend that kind of stuff. We went back to it for honest reasons in a more confessional frame of mind, and you expect that to be in the DNA of the film.

Q. Did you have any difficulty attracting the cast back to the project? Many of them have gone on to huge careers.

A. They were all instant when they got the script. Even though it wasn't finished, they were all in. It was like they were all embedded, and that was the point of it. It wasn't much money. We said, "We're not going to pay you a lot. You'll all get a very nice back end if it works, but we want to keep the price down. We don't want this to feel like it's cashing in. It's made in very similar principles to the first movie in terms of length and engagement and also that it's a shared film. It's about all four of you, and we will stick to that." It was the four of them, and of course, the point of it then is what's happened to them. Even the ones who have remained in Edinburgh have not [seen] each other, which is extraordinary. I've got friends at school I haven't seen for 20 years.

Q. Was there any trepidation going back to this world? Was there any particular pressure you put on yourself to make something culturally relevant again?

A. You have to be honest about yourself as a director. Although you want to make gestures toward [the original], and you want the film to be a fun experience, because no one wants to make films that are torture for people, but you're not that guy, and some of the boldness of the original is born out of complete innocence and naivete and stupidity. You can pretend to replicate that, but the audience will spot it. They're savvy. They know.

Q. There's a scene about midway through this film, where Ewan McGregor's character, Renton, takes one of the first film's tag lines "Choose Life" and starts holding forth about the internet era and people's subsequent self-obsession on social media. Was that an important element for you?

A. Yeah, one of the fun things is that you incidentally [have to] introduce the modern world. Renton's litany is updated to modern obsessions, and modern addictions (and, they are addictions). Way back then he was mocking people about washing machines. People weren't as addicted to their washing machines as they are to their iPhones now. It's gotten way worse, and the trail that spreads from those consumer products back to the factories is toxic. We all know it is. So, there's a bit of that "Modern life is rubbish" in there. But the speech, a very beautiful speech by John [Hodge], also contains something about personal loss, and it turns confessional toward the second half of it, and that's the reason to do it ultimately. The first half reads like a greatest-hits update, but actually the real root of it is he says, "I choose disappointment. Choose losing the ones you love."

Q. Two decades on, all of the actors look a bit different, but Robert Carlyle looks completely reimagined. He's built like a refrigerator now.

A. Yeah. That was him. He said, "I want him to look unhealthy, like he's put on weight." Prison food is [horrible]. It's stodgy and if you're not doing any exercise you're going to put on weight while you're in, so he bulked up. I think his instinct on the first film was right. It's the little guys that got nothing to lose who are really scary. That was his point about Begbie. Begbie was written in the original novel as a big guy, and he said, "I've got to play this. I know these guys, and it's the little ones. The big guys you can deal with." He said, "It's the little guys that are the real psychos."

Q. Were there any particular influences on this film that maybe weren't there in the first go-round?

A. Yeah, there was an amazing show when I was a kid on television, a comedy drama series in six parts called The Likely Lads, and it was a massive hit. It was about two young guys that just left school, and they were from Newcastle, an industrial city in the northeast of England, which had very thick accents. No one could believe it was a hit because it was one of the first times you'd seen drama on television and mainstream comedy drama with thick regional accents. Everybody loved it. It disappeared, finished, and then seven years later, they brought them back. Same guys, playing the same characters, and it was called Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads. They were the same but different ... I remember thinking, "That is amazing that you can do that." It's one of the magical things about time and the movies. It's the art form of time.

There's a scene where Renton is trying to escape from the deranged Begbie in a parking garage by jumping onto the roof of a speeding car as it winds its way down. I noted that this whole scene -- which should have been terrifying to him -- he actually had a big grin on his face. He's really enjoying this, even though it may kill him.

Yeah. It's adrenaline, isn't it? Do you know what I mean? It's like you're alive again. I think that's one of the reasons they come back together, because they're dead without each other. Even though one of them wants to kill Renton, at least they feel alive in the chase. I think the problem -- a big problem for guys -- we do age very, very badly. We hang onto the past. We don't think on living in the past, but you behave, to all intents and purposes, like you are. I think women look at us and just think, "They're so sad." Women measure out time much more sensibly than men. I think what happens is that when men get the excitement back again, it's like, "At least we've got something."

MovieStyle on 04/14/2017