LITTLE ROCK — If Arkansas succeeds in executing multiple inmates by the end of the month, despite several setbacks in court, it will show that states have found an effective way of repelling some legal challenges that have thwarted or delayed executions in recent years.

Arkansas and at least a dozen other states with the death penalty have been keeping secret how and where they are getting the lethal drugs for their death chambers — information that had long been publicly available.

The secrecy has helped blunt legal challenges over the lethal injection drugs, which states have had trouble obtaining in recent years because manufacturers don't want their drugs used in executions.

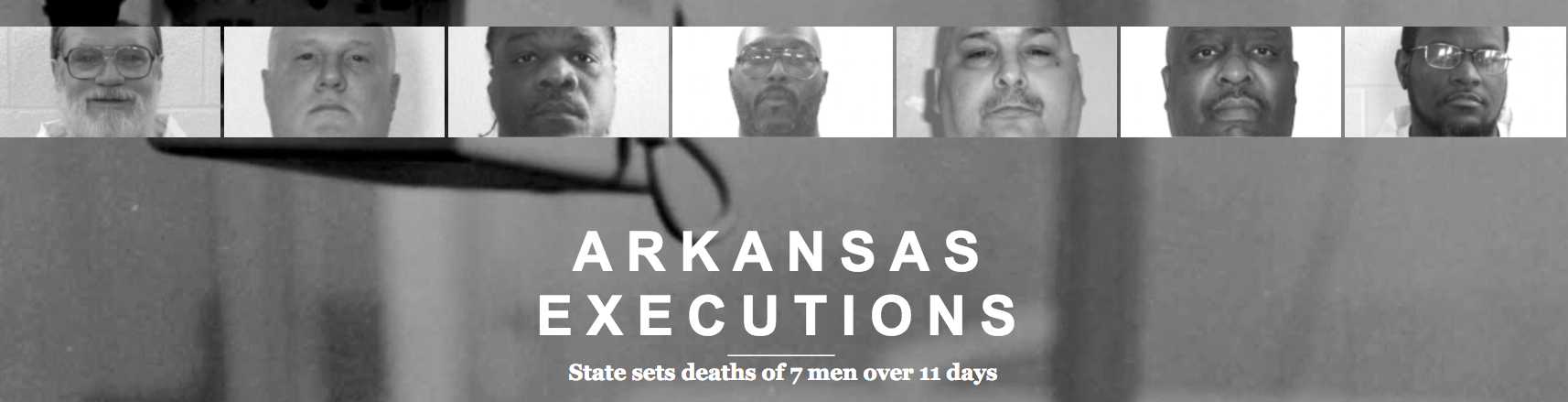

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

In recent rulings, state and federal courts across the country have upheld the legality of the new secrecy laws, despite opponents' complaints.

"These secrecy statutes are extremely effective at preventing challenges to execution procedures," said Megan McCracken, an attorney at the University of California at Berkeley Law School's Death Penalty Clinic.

With its new secrecy law, approved in 2015, Arkansas will be able to resume executions, which had been blocked since 2005 by legal obstacles and drug shortages. In 2011, the state lost a source of sodium thiopental, a sedative then used, disrupting the process.

Arkansas had hoped to execute eight inmates in 11 days, starting with two on Monday, because its supply of one of the three drugs it uses in executions will expire at the end of the month. Whether it will be able to execute anyone is uncertain, though. Courts granted stays to two of the eight inmates before a federal judge ordered a halt to all of them Saturday, leading the state to quickly appeal.

Also unclear is whether the secrecy will make it easier long-term to obtain the lethal drugs needed, as states hope. Gov. Asa Hutchinson said the secrecy law helped Arkansas find its new supplies, but officials won't say how.

It was not known whether a supplier provided drugs confidentially or, as one medical supplier claimed, whether the state might have diverted drugs that were intended for medical purposes. Three pharmaceutical companies have also objected to their products being used in Arkansas' planned executions.

"I don't think we would have acquired the drugs that we have without that confidentiality agreement," Hutchinson said.

The American Pharmacists Association has discouraged its members from providing drugs for executions.

Numerous executions have been placed in legal limbo in recent years after challenges based on the source of the drugs. Information about the drug's supply chain and handling is essential to ensure that inmates won't be subjected to cruel and unusual punishment, said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, which opposes capital punishment.

Details about production and transportation of drugs "are vitally relevant to the execution process," Dunham said.

But the states argued that the difficulty didn't come from problems revealed in the drugs' handling, but from public protests directed at manufacturers and suppliers for assisting executions. They said secrecy is needed to protect suppliers from threats or retaliation.

State courts have also upheld secrecy laws in Arkansas, Georgia and Oklahoma, and the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Arizona's drug secrecy in a 2014 case. A media advocacy group and the American Civil Liberties Union on Thursday asked Missouri's highest court to settle whether the state's prison system must reveal its execution drugs.

"At this juncture, plaintiffs have failed to present a persuasive case for the proposition that source knowledge is necessary to mount a meaningful, much less comprehensive, challenge to Ohio's execution protocol," U.S. District Judge Gregory Frost wrote in his 2015 ruling upholding Ohio's drug secrecy efforts.

Arkansas set such a crammed execution schedule because its supply of one of its three execution drugs, midazolam, expires at the end of the month. The sedative has been used in botched executions in other states.

Although Arkansas found sources for its three execution drugs, it took 12 days to obtain a new supply of vecuronium bromide and 67 days to replace its potassium chloride supply.

"Despite the confidentiality provisions, it is still very difficult to find a supplier willing to sell drugs to (the state) for use in lethal-injection executions," state Correction Department Director Wendy Kelley said in a court affidavit this month.

Absent details about drug sources, death penalty opponents may focus on questions about the drugs' reliability or how they are administered, based on flawed executions elsewhere.

Oklahoma inmate Clayton Lockett remained alive for 43 minutes, groaning and writhing on a gurney, after an intravenous line was improperly connected in his 2014 execution.

"The most information seems to come when there's a botch," said Deborah Denno, a professor at Fordham Law School and an expert on the death penalty.