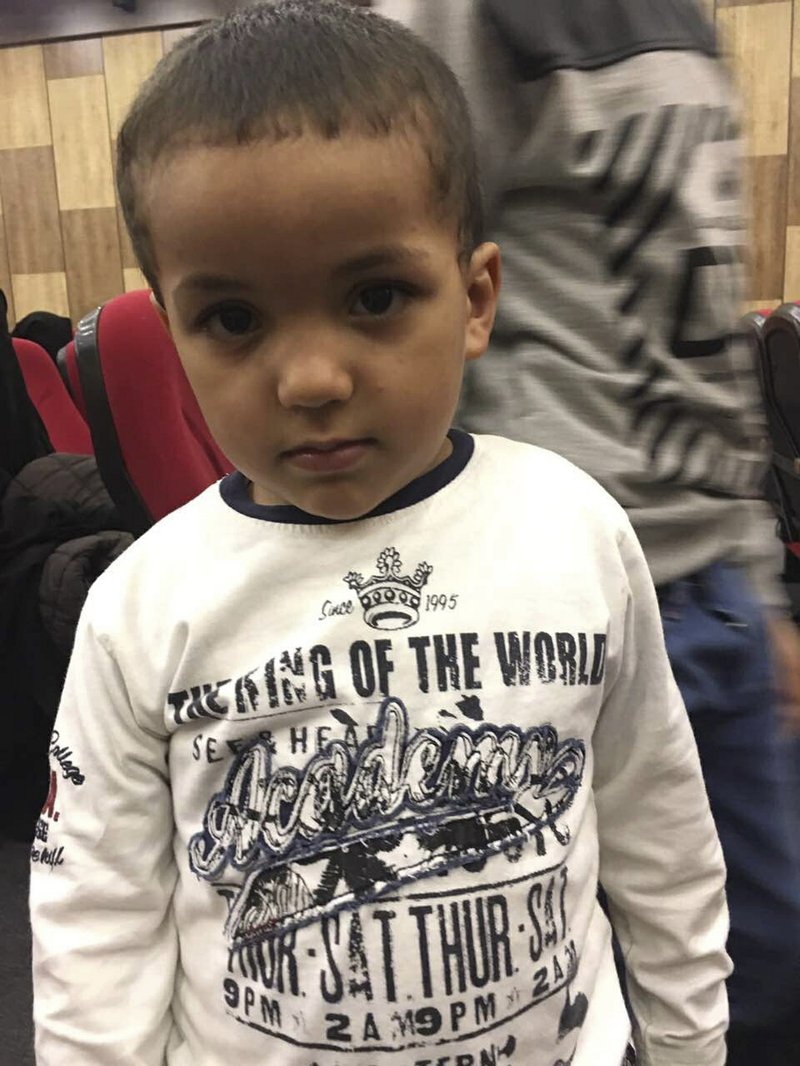

TUNIS, Tunisia -- Tamim Jaboudi is among hundreds of children fathered by the Islamic State's foreign fighters or taken to the self-proclaimed caliphate by their parents who are now imprisoned or in limbo with nowhere to go, collateral victims as the militant group retreats and home countries hesitate to take them back.

Almost the only home this toddler has known is a Libyan prison. He already marked one birthday there and in a few days will reach another, turning 3. He is an orphan of the caliphate: His parents, both Islamic State group members, were killed in an airstrike.

Since his parents were killed in February 2016, Tamim has been living among some two dozen Tunisian women and their children in Tripoli's Mitiga prison. The captives are under guard by a militia that tightly controls access to the group, despite repeatedly claiming they have no interest in preventing their return home.

"What is this young child's sin that he is in jail with criminals?" asked Faouzi Trabelsi, the boy's grandfather who has traveled twice to Libya trying to retrieve the boy and twice returned home empty-handed. "If he grows up there, what kind of attitude will he have toward his homeland?"

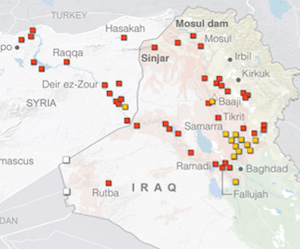

European governments and experts have documented at least 600 children of foreign fighters who live in or have returned from Islamic State territory in Syria, Iraq or Libya. But the numbers are likely far higher.

The children and families often find it impossible to escape Islamic State-held areas. And even if they do, their native countries are deeply suspicious and fearful of returnees -- sometimes even children. Tunisia, France and Belgium have all suffered major attacks from trained Islamic State fighters, and Western intelligence officials have said the group is deploying cells of attackers in Europe.

Although the Islamic State group says women have no role as fighters, France in particular has detained women returnees and some adolescent boys who it believes pose a danger. Young children often go into foster care or end up with extended family. In the Netherlands, anyone over 9 is considered a potential security threat, since that is said to be the age Islamic State extremists begin teaching boys to kill.

In Libya, their fate is particularly uncertain. The North African nation descended into chaos after the 2011 civil war, which ended with the killing of dictator Moammar Gadhafi. The country has been split into competing governments, each backed by a set of militias, tribes and political factions. Militias in December captured the main Islamic State stronghold in Libya, Sirte, effectively breaking the group's efforts to build territory there, at least for now.

Tunisia is working to bring back the women and 44 children held in Tripoli and elsewhere in Libya. But so far the only result has been repeated holdups and miscommunications.

"There is no wrong in being born in a conflict zone. Once their Tunisian citizenship is confirmed, they will have an individual treatment," said Chafik Hajji, a Tunisian diplomat who handles the cases of the country's citizens who joined the Islamic State.

Meanwhile, the women and children are held in a "big and comfortable" space in the prison, according to Ahmed bin Salem, spokesman of the Libyan militia that runs the facility.

Few if any of the women and children at Mitiga or another group of 120 foreign women and children jailed in the city of Misrata in Libya have valid identification papers, according to Hanan Salah, a Human Rights Watch researcher who specializes in Libya.

While it is unclear how many children were born in Islamic State territory in Iraq, Syria, Libya and elsewhere, a snapshot of the group at its height showed as many as 31,000 women were pregnant at any given moment, many of them wives of jihadis encouraged to have as many babies as possible to populate the nascent caliphate, according to the Quilliam Foundation, a British counter-extremism research group.

Quilliam researcher Nikita Malik said 80 British children were in Islamic State territory. France estimated 450 of its children, including about 60 born there; Dutch and Belgian intelligence each estimated 80 children.

By many estimates, Tunisia sent more jihadis to the war zones than any other country, with official figures at 3,000 and some analysts doubling that number.

Trabelsi's daughter and son-in-law were among them.

Trabelsi's daughter, Samah, married a young man from the neighborhood after a monthlong courtship, he said. The newlyweds left for Turkey, a common jumping-off point for Europeans and North Africans joining extremist groups.

Tamim was born there on April 30, 2014. The couple returned to Tunisia, then went on to neighboring Libya, where they remained for two years, he said.

The couple was among at least 40 people killed in a U.S. airstrike on an Islamic State training camp in the city of Sabratha in February 2016.

Six months later, word filtered back to his grandfather that Tamim was alive and in Mitiga. He began pressing to get him back.

One problem is that the Tunisian government is reluctant to deal officially with the militia that runs Mitiga prison since it is not a government body, while the militia demands the Tunisians talk to it directly.

Last week, an unofficial Tunisian delegation went to negotiate for the children, only to be turned back by the Libyans because it did not get permission prior to the visit. On Wednesday, another delegation was due at the prison but the visit was canceled when the group demanded to see the families and transfer them on the same day without going through proper procedures, according to the militia's spokesman bin Salem.

Information for this article was contributed by Maggie Michael of The Associated Press.

A Section on 04/23/2017