FAYETTEVILLE -- Years of water damage have stained the walls. Holes in the ceiling expose the second floor to the first. The staircase creaks, boards straining under the pressure of each footstep. A musty aroma taints the air, as if someone was rifling through the pages of an old book.

Jane Hunt Meade, the new owner of the storied Stone-Hilton House in Fayetteville, said she and her husband met with three architects about preserving the house. They all gave her the same answer: Tear it down.

"They said if anybody wanted to save it, work should have been done on it decades ago," she said late last month.

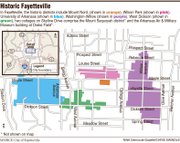

Years of neglect have led to the desolate state of the 1870s house. Some concerned neighbors in the Washington-Willow Historic District launched a campaign to save it. Others in the area worry more about what property limitations it could mean if they do, and what kind of building would replace it if they don't.

The future of the Stone-Hilton House spotlights the conflict between preserving history and protecting personal property rights.

The Stone-Hilton House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The house is a significant structure in the Washington-Willow Historic District in Fayetteville, according to its listing by the Arkansas Heritage Preservation Program.

A structure is considered historic if it is associated with a significant event, person or architectural style, or if it holds important information about the past, according to the register. It also has to be at least 50 years old in most cases.

Recognition alone won't save the house. One of the only protective measures for the house and any other historical building is for a city to pass a preservation ordinance.

A preservation ordinance allows cities to regulate what changes can be made to the exterior of buildings in historic districts. Regulations can include what materials can be used in renovation and what architectural features can be included. The aim is to make sure houses' appearances remain similar to the time periods of the original buildings.

No residential historic districts in Northwest Arkansas have ordinances protecting them. City officials and preservationists have struggled to get neighborhood support because an ordinance would constrain private property rights.

Commissions would enforce the rules by requiring property owners to obtain certificates of appropriateness before work could be done in the specified area. A certificate would verify that the proposed work would meet the architectural and historical standards of the area.

Three city ordinances protect nonresidential structures in Northwest Arkansas: the White Hangar at Drake Field in Fayetteville, which houses the Arkansas Air & Military Museum; a two-block area in Rogers' downtown; and the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in Springdale and its surrounding property.

Among Bentonville, Rogers, Springdale and Fayetteville, there are 11 historic districts and 482 properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places as either stand-alone structures or as part of the districts.

Many cities struggle to balance historic preservation and population growth.

Northwest Arkansas ranks as the 22nd-fastest-growing metropolitan area in the country, according to estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. Washington County's population has increased by a little more than 12 percent since 2010, and Benton County has had an almost 17 percent increase.

Residents often react negatively to the announcement of a new development in a historic area of town, said Greg House, owner of Houses Inc., a Fayetteville-based property management and development company.

"Whenever there is change, people push against it," he said.

Mark Zweig, founder of Mark Zweig Inc., a development firm based in Fayetteville, served on a historic district commission for a few years in a community near Boston. He said that experience leads him to think people here aren't ready for a preservation ordinance that would limit their rights as property owners.

"People don't realize if the historic commission has teeth and can enforce certain standards and maintain the integrity of what's there, they don't realize what the ramifications of that are," he said.

Being told what they can and can't do to their houses angers property owners, he said.

Jennifer Henaghan, a deputy research director with the American Planning Association, said development and preservation can be mutually beneficial.

"They have very similar goals," she said. "They both improve the revitalization of the area and boost tourism."

Henaghan said cities need to have a plan that details the expectations and regulations for historical preservation that residents can consult before conflict arises. Getting that information out would pre-empt a lot of problems, she said.

Zweig said many historic districts and homes are close to downtown areas or social hubs where residents want to congregate. The desire to be close to these areas has increased the value of the land over the years, he said.

The Stone-Hilton House is an example. From 1995 to 2015, the value of the land increased by 241 percent, while the building increased by 65 percent, according to county records.

Alternatives exist if a building can't be preserved, said Allyn Lord, director of the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. They include building similar-looking structures to replace old homes, and having someone photograph and record information about an old house before it's demolished.

House said that if the old buildings can't be saved, a new structure should reflect the old.

"It's easier to get the community to accept change if you're matching what is already there," House said. "That's not a radical change to the community you're involved in. Secondly, there's just a market appeal if there's a cool architectural integrity to it. It can be an asset."

Owners often preserve historic homes by adapting their use, such as turning a house into an office space or an old post office into a museum.

The Thaden House in Bentonville, built in the mid-1880s, was the home of famed aviator Louise Thaden. It was scheduled for demolition last year but now will be part of the Thaden School, said Clayton Marsh, founding head of the new private school in Bentonville. The house, which was dismantled, will be reassembled at the school's location.

Marsh said the house could be used as a gathering space for the community, a seminar room, a place to house art exhibits or a meeting room for the school's board.

The Lane Hotel in the Rogers Commercial Historic District is another example of reuse. The renovated hotel will open this school year as a campus of Haas Hall Academy, a public charter school.

Henaghan said companies throughout the country have been moving headquarters from suburbs closer to downtown areas. Google, for example, refurbished an old Nabisco factory for its offices in Pittsburgh in 2011.

The Department of Arkansas Heritage and the U.S. Interior Department offer tax incentives and grants to those who preserve historic properties. Local preservation societies also provide grants for homeowners to renovate their houses to align them with the era when they were built.

The Stone-Hilton House has been at the center of debate in Fayetteville since the Meades bought the home in May. Concerned residents were worried about what Hunt Meade planned to do with the home. Some appealed to the city's historic district commission, while others began a Facebook campaign to save the house.

The two-story brick house was built in the Georgian architectural style with Italianate details, according to the Save Stone-Hilton House Facebook page. The style combines symmetrical design with decorative elements such as intricately engraved doors and roof cornices.

Hunt Meade said she has every intention to build a home fitting the architectural integrity of the neighborhood. She has been approved for a building permit for a little more than $800,000 in a neighborhood where houses have recently sold for near a half-million dollars.

She also plans on trying to keep parts of the original house such as the fireplace in the first-floor living room, the basement and a few of the remaining cornices on the roof.

"There's no way anyone could restore that house, historic commission or not, and have it work out economically," Zweig said.

Metro on 08/06/2017