In July, National Public Radio released a list of the "150 Greatest Albums Made By Women." It starts (at 150) with the Roches' eponymous 1979 debut album and winds up with Joni Mitchell's Blue at No. 1.

Like all hierarchical listings, the point is to evoke quibbles, which lead to clicks, which some wizard somewhere knows how to monetize. For instance, NPR ranks The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill No. 2, just ahead of Nina Simone's I Put a Spell on You and Aretha Franklin's I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You, which is defensible only if you're talking about records and not artists.

Similarly, does Beyonce's Lemonade deserve a spot in the Top 10 absent its video component? And how are Carole King's Tapestry and Patti Smith's Horses not Top 5? (My Top 10 list would probably be made up entirely of records released from March 1969 -- Dusty in Memphis, by Dusty Springfield, which checks in at No. 45 on NPR's list -- to December 1979 -- The Pretenders, NPR's No. 60).

What's interesting is we still find it useful to produce lists like this, to remind us that hey, women make interesting music too.

When I was 15 years old and beginning to amass a record collection, I remember flipping through my crates -- sorted alphabetically by artist and chronologically by release date -- and being mildly appalled by the dearth of female artists.

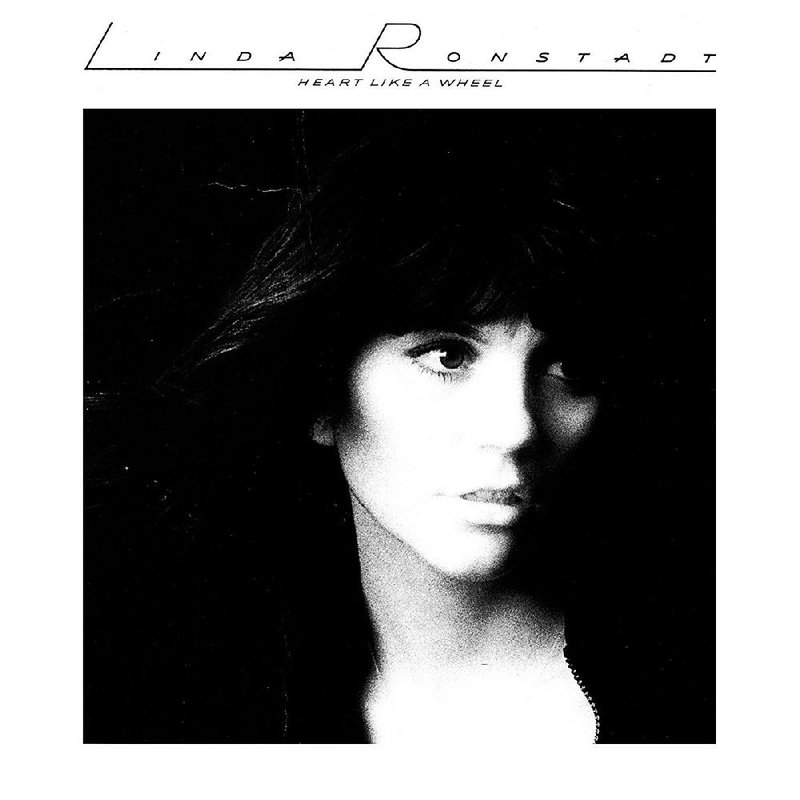

It would be misleading to suggest that as an adolescent male I thought a whole lot about issues of gender equity, but on my very next trip to the record store I bought Linda Ronstadt's Heart Like a Wheel. It wasn't the first album by a female artist I'd added to the collection -- I had appropriated my parents' Patsy Cline albums and acquired a few forgettable promotional records by women. But Ronstadt's was the first one I'd spent my money on.

It might be saying too much to say it changed my life, but it kind of did. Heart Like a Wheel is a thrillingly sung, deeply intelligent project that redeems some of the worst cliches of '70s pop/country balladry. It's basically Ronstadt fronting the Eagles (Don Henley, Glenn Frey, Timothy B. Schmit) augmented by singers-songwriters Andrew Gold and J.D. Souther, with backing vocals by Emmylou Harris, Maria Muldaur, Cissy Houston, Wendy Waldman and Clydie King. Sneaky Pete Kleinow plays pedal steel guitar and Herb Pedersen banjo, while David Lindley plays fiddle. All this talent was marshalled by producer Peter Asher, formerly half of Peter and Gordon, brother to Jane and manager of Ronstadt and James Taylor.

Reading those credits, you might conclude Heart Like a Wheel was less a Ronstadt album than an all-star effort she karaoked over. She didn't write the songs -- they were by the likes of Clint Ballard Jr. ("You're No Good"), Lowell George ("Willin'"), Phil Everly ("When Will I Be Loved"). And Asher's inventive, subtle arrangements are set with a jeweler's precision.

Still, it's Ronstadt's name above the title, and her command of the material is impressive. "Different Drum," her first hit, with the Stone Poneys, was released in 1967, and she'd been nominated for a Grammy for 1970's "Long, Long Time" -- but Heart Like a Wheel opened the floodgates for her brand of grown-up, torchy white blues.

For a while, I decided to buy at least one record by a female artist for every record bought by a male artist. This led me directly to Joni Mitchell, whose 1975 album The Hissing of Summer Lawns opened my 17-year-old eyes. It wasn't well-received by critics. In Rolling Stone, Stephen Holden awarded it zero stars and allowed that while it was "cerebral" and offered "substantial literature," there were "no tunes to speak of" and asserted that the musicians' "uninspired jazz-rock style completely opposes Mitchell's romantic style." It was "a great collection of pop poems with a distracting soundtrack," Holden wrote.

Holden's review is very strong, even if, like my contemporary Prince, who often cited Summer Lawns as one of his main influences, you think he gets it wrong. We all come to this stuff in our own way, and as a teenager I was more impressed by clever lyrics than I should have been. Summer Lawns was a break from the confessional singer-songwriting vein Mitchell had pursued on her previous albums, moving more into social commentary and philosophy than personal excavation. There was no "I" on the lyric sheets -- the singer took on an omniscient point of view as she related the stories of characters who were involved not in heartbreak or ecstasy but in cooler transactions.

While writer and musician Winston Cook-Wilson once began a piece by saying Summer Lawns would "never be an initial gateway to Joni Mitchell," it was exactly that for me. I had heard Court and Spark but hadn't listened hard. I hadn't even been aware of Blue (1971), which on some days is my favorite record of all time. Summer Lawns not only sent me deep into Mitchell's catalog but stirred a vague and early interest in jazz. Maybe it wasn't the best jazz (though the early '70s iteration of Tom Scott's L.A. Express is underrated) but it was a start.

Another thing about Summer Lawns -- unlike Heart Like a Wheel, there was no doubt about the creative engine behind it. Mitchell wrote the songs (with the exception of the Johnny Mandel-Jon Hendricks tune "Centerpiece"), produced the album and "drew the cover and designed the package."

...

By 1978 I had a sense of myself as a sophisticated consumer of pop culture. I had lived abroad, had my own apartment, a radio show and an electric guitar I sometimes played in the company of like-minded young men. I had no business buying Blondie's Parallel Lines and Plastic Letters for the cover photos.

On the other hand, that's what album covers are for -- to entice susceptible consumers. Blondie may have been a band, but its focal point was a platinum-haired former Playboy bunny named Debbie Harry, a formidable vocalist and savvy marketer whose complex mingling of intellectualism and diffident sexuality was calibrated to evoke crushes from the sort of boys who, on the cusp of the '80s, found themselves transitioning from ripped jeans to skinny ties.

Plastic Letters' cover featured a pink-dressed Harry sitting on the bumper of a police car, with the three other dudes in the band hanging around. It evinced a deliberate trashiness closer to the aesthetic of John Waters (who would, a decade later, cast Harry in the movie version of Hairspray) than the downtown Warhol scene which spawned the band.

With songs that blared like tabloid headlines -- "Bermuda Triangle Blues (Flight 45)," "Youth Nabbed as Sniper" and "Contact in Red Square" -- alongside a faithful cover of Randy and the Rainbows' 1963 hit "Denise" (re-titled "Denis") and the ethereal "(I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear," written by bass player Gary Valentine, who left the band for a solo career before the album was recorded, Plastic Letters established Blondie in Europe while delivering them a cult in the U.S. Five months later, Parallel Lines and "Heart of Glass" made them huge pop stars.

...

In the NPR list, it's Lucinda Williams' 1998 album Car Wheels on a Gravel Road that gets the glory -- it comes in at No. 18. It's widely considered Williams' best record and one of the best of the 1990s. I'm particularly fond of the album. Her father, the late poet Miller Williams, played it for me months before it was released when we visited him in Fayetteville. When it was released, I wrote a review that would be embarrassing if I didn't still believe in its validity: "It is replete with grace and a kind of tough magic. It rocks. It induces shivers. It bleeds and moans and cracks a wry grin as it brushes its hair back from its eyes. Oh my baby."

But Car Wheels is not my favorite Williams album. For that you'd need to go back to 1988's Lucinda Williams, which was her third album, after her Folkways blues albums Lucinda and Happy Woman Blues.

Lucinda Williams was recorded for Rough Trade, a British label that specialized in punk and ska acts. While it wasn't a commercial hit, it earned her a small but intensely loyal (and somewhat obsessive) following and a burgeoning reputation as a "musician's musician."

Rough Trade folded soon after the album was released, leaving her without a record company. RCA snapped her up but when it presented her with sugary, radio-ready mixes of her songs she told them "no thanks" and walked out on Elvis Presley's old label.

Thanks to digital distribution, Lucinda Williams is easy to find these days, and songs like "Passionate Kisses" and "I Just Want to See You So Bad" have become neo-standards. It's the place where a great songwriter finally found her footing, and along with contemporary work by Steve Earle could be seen as the foundation of the Americana movement.

...

Even more interesting than NPR's list is venerable critic Ann Powers' companion essay, "A New Canon: In Pop Music, Women Belong at the Center of the Story," also on the NPR website.

Powers makes the case that the story of popular music is told through the "great works of men," with women forever on the margins.

"Back in the 1980s, in my college women studies classes, I was taught to be suspicious of the pervasiveness of the 'pseudo-generic man' -- the assumption that a male perspective can stand for all perspectives," Powers writes. "Today, myriad identities across the gender spectrum flourish within our shared social media spaces and the conversations generated there. Yet in popular culture, and especially in music, the pseudo-generic man still rules."

She's right, and I'm not sure what to do about it other than feel a little guilty. And wonder where the great female producers are. Most seem to be like Mitchell -- artists involved in producing their own projects. If there is a female Phil Spector or Rick Rubin, I can't come up with her name.

OK, Lauren Christy is half of the production team The Matrix, known for their work with Liz Phair (who, if this essay had unlimited space, would certainly merit mentioning). Linda Perry has transitioned from artist to producer, working with Pink and Christina Aguilera, among others. Back in the day, Sylvia Robinson produced some seminal hip-hop recordings. Emily Lazar is a top mastering engineer.

I'm probably overlooking someone. I hope so.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 08/06/2017