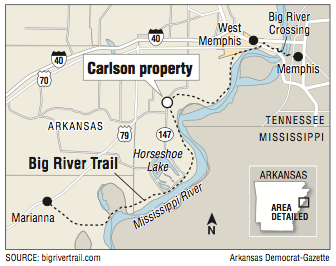

ANTHONYVILLE -- A lawsuit in Crittenden County and maybe $200 worth of steel posts and wire have thrown a kink into the use of a trail for bicyclists and hikers topping 70 miles of levees along the Mississippi River between West Memphis and Marianna.

The Big River Strategic Initiative last fall won rave reviews with the grand opening of the Big River Crossing -- a mile-long pedestrian and cyclist route across the Mississippi River, from West Memphis to Memphis, on the long-abandoned 100-year-old Harahan railroad bridge.

"We had great things going with that event, a lot of positive momentum to drive economic development and tourism throughout eastern Arkansas," said Dow McVean, chief executive officer of Big River Strategic Initiative LLC, which helped raise and spend some $18 million on the project.

There were high hopes, also, for two related projects -- the 70-mile levee-top Big River Trail to the south and development of Big River Regional Park with its 6.8-mile loop around some 450 acres of Crittenden County farmland and wetlands just north of the Big River Crossing.

"We're like all good Southerners who want to see this area grow and prosper," McVean said. "Getting tourism -- it's low-hanging fruit -- is a way to do that."

A lawsuit by Ralph Carlson of Proctor, about 20 miles south of West Memphis, and Ward Walthal of Memphis, who owns farmland in Crittenden County, has complicated both projects.

Carlson and Walthal sued the St. Francis Levee District in March, contending that the district, which holds right-of-way deeds with Carlson, Walthal and other landowners for access along the top of the levee, had no authority to open a recreational trail across their land. The right-of-way deeds, according to the lawsuit, allow access by the levee district only for "construction, enlargement and maintenance" of the levees, built decades ago by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for flood control.

The district's actions -- which have included surfacing the levee-top trail with crushed limestone and installing special gates at certain levee crossings to allow pedestrian or cyclist access -- subjected the two landowners to "repeated and continuing" trespasses, the lawsuit said. The levee district didn't have legal authority to grant public access to the levees through a third party, the Big River Strategic Initiative, the lawsuit said.

"We've got no ax to grind in the lawsuit," McVean, whose Big River organization isn't a defendant in the lawsuit. "But we believe the levee district, through the Corps of Engineers, does have a role in bringing recreation. It's not a primary mandate, but it is a secondary one, just as the Corps does with recreation and fishing areas around locks and dams."

Big River's ultimate goal -- a reachable one within a few years, McVean said -- is to tie all Arkansas bike routes, like one being developed along the Mississippi River at Arkansas City, into one route, stretching from St. Louis to New Orleans.

No hearings have been scheduled in the lawsuit.

Blocked gates

The Big River Strategic Initiative lobbied the St. Francis Levee District's board of directors for its support for some five years, and in early 2016 all 19 board members voted to join the project.

While much of the 70-mile route is easily accessible at some 20 entry points, some landowners and farmers over the years have put in wide gates, usually padlocked, across levee roads to contain livestock or limit vehicular traffic.

Using a $100,000 state grant, the levee district purchased and installed 49 special gates that could be aligned with the cattle gates and are just wide enough for a cyclist or pedestrian to continue along the trail.

Six of those special gates were on tracts owned by Walthal and Carlson, according to the lawsuit.

Sometime after cyclists first began using the trail last fall, the special gates on Walthal and Carlson's property were blocked with steel posts driven into the ground and laced with wire. Periodically, "no trespassing" signs have been posted.

Levee district workers have removed the wire when they hear about it, as a safety hazard, but the wire often is replaced. "We are not going to allow the wire," said Rob Rash, the levee district's chief engineer. "When we hear about it, we'll take it down."

Of the many landowners along the trail, only Walthal and Carlson have objected, Rash said. "That's the only place that's shut off," he said. "No other property owners have done this. The rest is still accessible."

"It's really a beautiful trail, and then it's really intimidating, and dangerous, to go down there and see the gates blocked off with wire," said Steve Higginbothom of Marianna, a former state senator and president of the levee district's board.

Higginbothom said he knew of no incidents on the part of trail users to prompt the gates' blockage and no confrontations between users and landowners. "I think they just see the signs and the blocked gate and make a U-turn," he said.

A reporter last week drove along Blue Lake Road, also known as Crittenden County Road 143 southeast of Anthonyville, where two bicycle gates have been installed, about 1,200 feet apart, atop the levee road that runs through Carlson's property. At the southern gate, two workers were trimming weeds and grass. The visitor veered north, to take photographs of a bicycle gate blocked by wire and steel T-posts common on farmland.

Within a few minutes, another man in a pickup drove up the levee to check on the unannounced visitor. The reporter identified himself, and the man in the truck allowed, with a smile, that he "might be" Carlson. It was a friendly meeting, like coffee-shop talk every morning among farmers and friends, about the nice weather, the damage to crops allegedly caused by the dicamba herbicide, and then the bicycle trail and lawsuit.

"I guess I'm the bad guy in that," Carlson said with a smile. Otherwise, he declined comment and said maybe his lawyer would answer questions. With that, he drove off, but slowly enough to make sure his visitor left and left safely.

Trespass remedy

Neither Carlson's attorney, James Hale III of Marion, nor Philip Hicky, a Forrest City lawyer representing the levee district, returned telephone calls for comment Thursday.

The plaintiffs, in their lawsuit, have no beef with trail users themselves but said the "only remedy to stop trespass is to arrest or sue the numerous bicycle riders as they trespass across their property."

"This will entail exposure to litigation to many innocent bicycle riders who have no idea access across Plaintiffs' property has not been obtained from the landowners," according to the lawsuit. Carlson and Walthal have asked a judge to issue a temporary injunction, halting public access through the property, until the lawsuit is decided.

A spokesman at the Crittenden County sheriff's office said the agency hasn't heard of any problems along the route.

The lawsuit and the barred gates haven't gotten a lot of attention, although some cyclists have occasionally posted comments on social media about the matter, said McVean, whose Big River Strategic Initiative is run out of McVean Trading and Investments in Memphis, a company his father Charles founded in 1986.

Besides an occasional grant or money from loose-knit fundraisers organized by cycling enthusiasts, the effort is funded by the McVean family, Dow McVean said.

The effects of the Carlson-Walthal lawsuit can be felt 20 miles north of Anthonyville, near West Memphis, where Big River Strategic Initiative has been developing Big River Regional Park. The group has won easements from several landowners and farmers for the 6.8-mile pedestrian and bicycle loop with unobstructed views of the river and the Memphis skyline.

But the route, as first planned, had to be altered -- to skirt a 111-acre field that Carlson farms along the shoreline.

SundayMonday Business on 08/13/2017