The stories, in all their brutality, were too hard to ignore.

Guy Lancaster was researching his 2014 book Racial Cleansing in Arkansas, 1883-1924: Politics, Land, Labor and Criminality. As he scanned newspaper reports on microfilm machines, the headlines whizzing by, he began to notice something: a startling number of stories about the lynchings of black people.

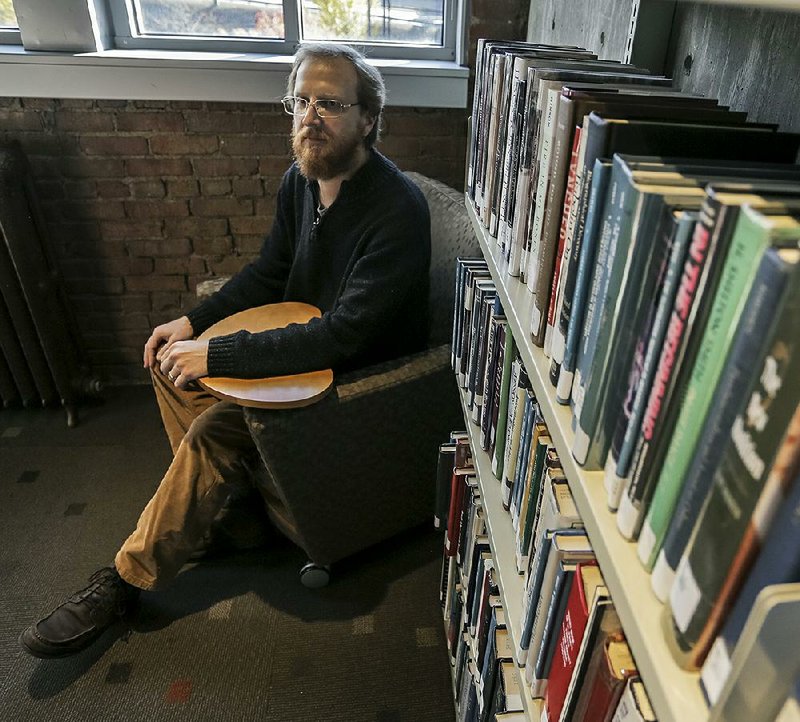

"I kept coming upon these lynchings and thinking that I need to go back and revisit that," Lancaster says in his third floor office at the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, where he is editor of encyclopediaofarkansas.net. "I would take notes and keep cranking through and there would be another one."

Soon, his notes were piling up and the idea for a new book took shape.

"I thought it would be cool to do an edited volume of individual essays allowing each writer to focus on a particular theme or incident," he says.

The result is Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840-1950 (University of Arkansas Press, $39.95), edited by Lancaster and featuring pieces by Kelly Houston Jones, Nancy Snell Griffith, Randy Finley, Richard Buckelew, Vincent Vinikas, Todd E. Lewis, Stephanie Harp, Cherisse Jones-Branch, William H. Pruden III and Lancaster.

Seven of the essays were written for the book, while three -- Vinikas' "Thirteen Dead at St. Charles: Arkansas's Most Lethal Lynching and the Abrogation of Equal Protection," Lewis' "Through Death, Hell and the Grave, Lynching and Anti-Lynching Efforts in Arkansas 1901-1939" and Lancaster's "Before John Carter, Lynching and Mob Violence in Pulaski County, 1882-1906" -- were published elsewhere and have been revised and expanded here.

The collection is exhaustive in its scope and unflinching in its reporting of Arkansas' history of hate, fear, terror and violence. The book also deals with the sometimes chillingly offhanded news coverage of these events, the language and the repercussions.

In "Doubtless Guilty: Lynching and Slaves in Antebellum Arkansas," Jones, an assistant professor of history at Austin Peay University in Clarksville, Tenn., explores "the phenomenon of slave lynching" and how "the incentive to profit and the need to uphold white supremacy could be in conflict in a slave system."

She quotes lynching expert Christopher Waldrep's argument that slavery promoted "extralegal violence," with whites' imagined right to punish black people outside the law originating in the days of slavery.

In his chapter, Vinikas, a professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, unearths details about the bloody lynchings that left 13 dead over a week at St. Charles in 1904.

The St. Charles terror began when a black man hit a white man with a jug, or perhaps a table leg. As he was being taken to jail he grabbed a policeman's gun and fled. Over the next week, vigilantes went on a killing rampage. At one point, 60-70 black people, including women and children, were rounded up and forced by a mob into an old building, with plans to burn the building with them in it.

The burning was averted, but six people were taken from the building and shot. Five were killed. The sixth man was able to crawl away, but was found the next morning and shot to death.

"By the early 20th century," Vinikas writes, "the lynching of African Americans was as common as it was catastrophic throughout the American South." He quotes A Festival of Violence, a 1995 study of the 10 Southern states by Stewart Tolnay and E.M. Beck, who concluded that there were almost 2,500 black fatalities between 1882-1930, which amounts to a black person being lynched on an average of one a week during that time.

In Arkansas, during the period covered in the book, there were over 360 lynchings, Lancaster says.

A twist to the usual lynching story is explored by Buckelew in "The Clarendon Lynching of 1898: The Intersection of Race, Class and Gender." Buckelew tells the plight of prominent merchant John Orr and his wife, Mabel. Though theirs seemed to be a charmed life of prosperity, church and family, the marriage was apparently an unhappy one.

Mabel conspired with her servants to kill John Orr for $200. Orr was shot to death after he returned home from choir practice.

When her story began to unravel, Mabel Orr and her accomplices were arrested. She committed suicide in her cell, while a mob stormed the jail and hanged five others, including women, arrested in connection with the murder.

A reward of $200 was offered by Gov. Daniel Webster for the arrest of any member of the mob, but, as with most of the other lynchings in the book, there were no arrests.

The savage 1927 Little Rock lynching of John Carter is covered by Harp: "Stories of a Lynching: Accounts of John Carter, 1927" -- and Lancaster: "Before John Carter: Lynching and Mob Violence in Pulaski County."

Carter was the black man accused of accosting a white woman and her daughter on the morning of May 4, although there were also reports that he was just trying to help them after a backfiring car startled the horse pulling their wagon.

A mob later found Carter and he was hanged from a telephone pole, where between 25 and 50 gunmen fired 200-300 shots into his body.

It gets worse.

Carter's body was taken to the intersection of Ninth Street and Broadway, the heart of the black business district, was doused with gasoline and burned. Pews were ripped from the nearby Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church to fuel the fire.

Witnesses also said that Pulaski County Sheriff Mike Haynie saw the hanging and shooting, although newspaper reports said he arrived afterward.

"You have to wonder in the end what the psychological effect is on people coming out of that," Lancaster says of lynching violence. "There has been a lot of study done on post-genocide societies like the former Yugoslavia or Rwanda and encountering the guy who murdered your family at the local market. That was Arkansas for a lot of people."

He recalls attending a symposium hosted a few years ago by the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center in Little Rock on Carter's lynching.

"What struck me most was that, in the black community, you're talking about grandchildren and maybe great-grandchildren of people who were alive at the time who had heard these stories. In the white community, as there began to be shame attached to these events, you didn't pass along the fact that your grandfather lynched a man.

"So in the narrative of who we are, if we want a cohesive United States, we have to take an honest look at this history and try to form a new narrative out of it. I think the more we bring this up, the more we uncover, the more we will advance to that new narrative, a narrative that includes us all."

Bullets and Fire is just scratching the surface, he says.

"There are so many incidents in this book that get a brief mention that could be their own studies. There is much more research that needs to be done in this area, especially in Arkansas, which tends to be overlooked even by Southern historians."

Style on 12/03/2017