Dr. Michael Greger wrote the 2015 best-seller How Not to Die, and so dying before he was thoroughly old would be, yeah, worst-case scenario.

"A bad way to go," he said cheerfully.

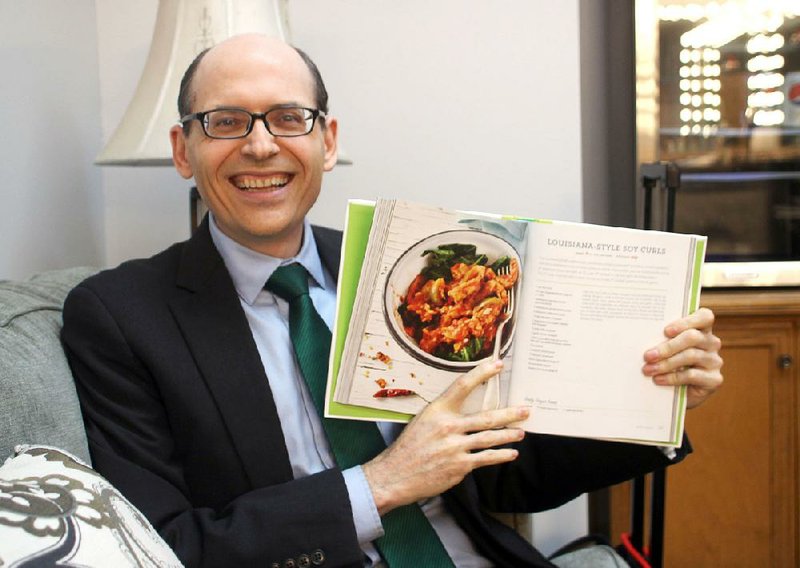

How Not to Die and its just-released companion, The How Not to Die Cookbook (Flatiron, $29.99), assert that the common mortal diseases are caused or encouraged by failing to eat enough -- enough nutrient-rich plants.

As Greger does through the website nutritionfacts.org and its amusing videos, How Not to Die recommends certain foods as more helpful than others, based on comparative research studies. "Science!" he says.

It fries his grits that people don't know science has demonstrated -- 40 years ago -- that eating a whole-foods, plant-based diet can reverse the No. 1 killer of men and women, cardiovascular disease. Nathan Pritikin did the science in the 1970s. As readers learned in How Not to Die, one of the heart patients Pritikin saved was Greger's grandmother.

In Conway on Dec. 2 with plenty of time to kill before his appearance on-air for an AETN pledge drive, the 45-year-old general practitioner and nutrition missionary sipped some black chai tea and laughed at himself. "Dying's bad enough," he agreed, "but then dying with a book, How Not to Die? Yes! That was the irony of my elderberry incident."

Elderberry incident?

"You don't know about the elderberries?"

We knew about his incident involving alfalfa sprouts, a bout of food poisoning described in the part of How Not to Die that urges readers not to eat alfalfa sprouts. They are one of his red-light foods. Traffic lights -- red, yellow, green -- illustrate his philosophy that foods are not so much good or bad as they are better or worse. Gobble green-light foods daily; limit yellow-light foods; avoid the red lights.

He and his wife planted an elderberry bush in the garden of their Maryland home a few years ago, but it bore its first crop of berries just this year. This delighted his wife, who likes birds, and intrigued him because elderberry is used in teas and preserves. "I like to eat," he explained.

Elderberries take time to mature. "Finally it was ripe. These big, lustrous black berries, just a couple of months ago."

He made an elderberry smoothie instead of using blackberries from the freezer. "Local! Organic! I put in massive amounts."

So he starts drinking his smoothie, and then forcing himself to drink it. "And it tastes terrible. But it's so healthy. ... Thankfully, my wife saw me grimace and passed, didn't want it. I just felt so righteous because I'm eating so healthy."

About 45 minutes later, drool began to drip onto his computer keyboard.

"But I'm so studious I'm still typing away, just trying to ignore it, as if it will somehow go away. And then ... and then ... the abdominal pain ... Such a violent, violent reaction."

He didn't die and so was able to open Google and learn, "Raw elderberries are poisonous!" They contain a cyanide compound that's made harmless by heat.

Greger told the story with the same relish and hilarity he brings to exposing deceptive research. It fits into his message that understanding what's in what we eat can save our lives -- which he has been on a mission to promote since med school.

"Because of my grandmother who was saved by Pritikin in the late '70s," he explained. Diagnosed with end-stage heart disease at 65, out of options for bypass surgery, too feeble to walk, thanks to Pritikin's plants and aerobic exercise she lived to be 96.

"It really affected me," he said. "I mean just the injustice of it all, that there was this kind of miracle cure that was just being buried. Lost to the world down some rabbit hole. So hundreds of thousands of people continue to die unnecessarily."

He wanted to do for everyone else's family what Pritikin did for his family. "So, until people stop dying of easily preventable stuff, I will keep doing what I'm doing."

And if he does happen to die early?

"It will be the bus that hits me," he said. "It's going to be the plane that goes down."

But Greger does have a "very exciting" heart condition, dextrocardia -- his heart is in the righthand side of his chest. He learned about it from the battery of tests third-year med students took to ensure they didn't have tuberculosis.

His department chairman had great fun using him to freak out his residents: Here, bring your stethoscope, do a chest exam on him.

"I said what's the life expectancy? Is this going to mean anything? He said there aren't enough people ever described in the literature, we have no idea what the natural history of it is."

If his heart did do him in, he said, the headline should say, "Thanks to his healthy diet he made it all the way to" (fill in the blank).

"But hopefully," he said, "it won't be, 'He lived 46 years with this crazy heart condition.'"

ActiveStyle on 12/11/2017

CORRECTION: Dextrocardia is a congenital anomaly in which the heart occupies the right-hand side of the chest cavity. An earlier version of this story spelled it incorrectly.