Michael Moore got out of jail last summer. He was homeless, unemployed and recovering from drug addiction. He often walked more than 10 miles a day from Rogers to drug court in Benton-ville or to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. He slept in a Rogers field near a KFC that gave him a job.

When Moore earned enough money to buy a tent or an air mattress, he went for the mattress. Better to have something soft to sleep on.

Every now and then he had enough to pay for a week or two at a motel that cost about $30 a night, an extravagant amount when multiplied over a month, but all that Moore could afford. Saving enough for a $550 apartment’s deposits and utility fees and application and furnishings was essentially impossible with motel, laundry and food bills on a minimum wage, he said.

Moore soon met Dean Vlaovich, who works in information technology in Lowell and is one of several volunteers who provide cooked meals weekly at the motel. Vlaovich asked Moore about his days, found him a new pair of shoes and, after Moore warmed up to him, started giving Moore what both men called homework assignments.

The first week, Vlaovich suggested Moore save $20 and get an ID. Another week, the goal was figuring out where Moore still owed money. Later it was getting his birth certificate, then finding a better job.

Moore did them all. He got hired at Tyson Foods and now works as a forklift operator there. Vlaovich’s volunteer group, spearheaded by Mercy Northwest Arkansas’s 8th Street Ministry, found him a donated car and an apartment and covered the deposit about three months ago.

“They changed my life. I can go nowhere but up,” Moore said this month.

He’s still wearing the shoes Vlaovich brought him, and says he’ll probably keep them forever. “I got a chance in life because I knew what it was like to be clean and sober and to have something.”

JOINING FORCES

Moore’s story and the ministry that helped him are examples of how local people, businesses and nonprofits are working together in more ways to prevent and overcome homelessness.

The Rogers ministry started about two years ago and includes a women and children’s shelter called Restoration Village, about two dozen churches and businesses, and other groups. All of them provide food, help and listening ears for dozens of guests of all ages at a Rogers motel. The initiative is working to expand to at least one location in Bentonville, said Sister Lisa Atkins, a member of the international Sisters of Mercy who works as an advanced practice nurse and community health worker at Mercy’s hospital.

Other examples of the trend abound. The Northwest Arkansas Continuum of Care, an umbrella group meant to connect all of the area’s services and resources for people lacking housing, has joined with Fayetteville’s 7 Hills Homeless Center and other groups to compile a comprehensive list of chronically homeless people. The Continuum plans to run a regional homelessness survey in January, a year sooner than expected.

Continuum members also increasingly use an online platform called Hark, developed by the nonprofit Center for Collaborative Care, that allows them to privately and safely refer clients to each other for different kinds of help.

“It feels so cohesive,” said Angela Belford, chairwoman of the Continuum’s board. “It’s really amazing, the efforts that have been going on.”

Glenn Miller, missions coordinator for Fayetteville’s Genesis Church, met one recent afternoon with a client to talk about her progress getting a deposit together for an apartment. She was injured at work and receives disability benefits but had been sleeping in her car, which Miller said probably contributed to her bronchitis. Miller joined her case after Hark notified him she couldn’t afford the $25 application fee for the apartment.

Miller offered her a microwave and blankets for her new place and prayed with her for a moment, his hand on her shoulder. “It’s going to work out,” he told her, handing her a flier for an upcoming breakfast at the church.

He said later, “I think the community’s coming together more than I’ve ever seen.”

Miller emphasizes personal responsibility and people helping themselves as much as possible, encouraging them to find jobs or help with the search for open apartments.

“We try to get them to partner with us,” he said.

Sherman Terry said he became homeless after moving to the area from Little Rock with a partner who used drugs. Ozark Guidance, which provides mental health services, helped him and placed him in an apartment near downtown Fayetteville for about $250 a month. He also works part-time at Genesis, he said during a break from hanging up Christmas decorations there.

“It’s a start for me, and I didn’t have anything,” Terry said.

The push toward forming a community-wide network of help for homeless people hasn’t yet reached everyone. Melisa Laelan, founder of the Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese, said earlier this month she hadn’t heard of the Continuum.

The Marshall Islander population is about 12,000 in the region, according to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. The community’s households are often large, including extended family members, and often low-income, according to interviews and Census data.

Laelan said she has seen more islanders pushed to living in motels or unable to buy houses because of unfamiliarity with the banking system. Several men last summer lived in a camp in Springdale, an event unheard of in the tight-knit community. The coalition helped them find jobs but doesn’t have the resources to help with rent or deposits, Laelan said. The coalition’s director, Lucy Capelle, and her church have been working on saving donations for that kind of need.

Laelan called the idea of joining with the Continuum wonderful.

A PERSISTENT PROBLEM

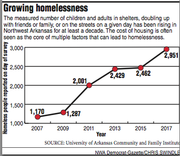

A 24-hour survey early this year from the University of Arkansas’s Community and Family Institute found about 3,000 people in Benton and Washington counties were in shelters, doubled up with friends and family, on the streets or otherwise lacking stable housing. The number more than doubled from 2007. About half were children in public schools.

Many organizations have long worked to address the issue. Several cities use federal Community Development Block Grants to help low-income people get into housing or pay for repairs to aging houses.

Karen Beckner, who lives with her mother near downtown Springdale, got a grant for $30,000 through the program to fix a leaking roof, repair the bathroom floor that was caving in because of the leak, upgrade the windows and doors and install central heating and air conditioning.

Beckner and her mother both receive Social Security benefits, and the possibility of having to live in her $105,000 home with such serious issues for the rest of her life was devastating to contemplate, she said.

“I just didn’t have any options,” she said, praising the city program. “I’m overwhelmed with this, because even the contractors were wonderful.”

Several groups tackling homelessness reported seeing the rise in the problem firsthand. Miller said 50 to 60 families every week come into his church asking for help with rent or deposits or food, more than ever in his seven years at his post. He works with property managers to vouch for tenants they might not otherwise accept but said he’s essentially run out of ones with units to spare.

7 Hills’s day center in south Fayetteville is expanding its laundry facility and doubled its food pantry in part because monthly clients have increased from 480 in a typical month to 560, director of operations Solomon Burchfield said in November.

Continuum and 7 Hills recently began sending people to homeless camps and other locations to assess who has been on the streets for extended periods of time, Bel-ford said. The Continuum plans to hold a community meeting, perhaps in February, to report on the data gathered. The list is critical to showing how big the need is for services aimed at this particular group, she said.

“Together we can help everyone,” Belford told several dozen people at a November event at Genesis about possible solutions. “Homelessness is a solvable problem.”

HOUSING AND MORE

The reasons for homelessness can vary widely and include substance abuse and other health problems, failed relationships, convictions and poor credit histories, advocates say. But housing and its costs are often at the center of them all, amplifying those problems and making them harder to escape.

“Ninety percent have a need they just can’t break through,” Cinthia Vlaovich, a volunteer at 8th Street Ministry and Dean’s wife, said about the clients.

Census estimates show about two-thirds of Northwest Arkansas households with incomes less than $35,000 last year paid more than 30 percent of their income on housing. Federal agencies and other groups typically use that proportion as a broad definition of unaffordable housing. Miller said many of the people he sees are paying more than half of their incomes.

Most Continuum members aren’t in a position to build housing, Belford said, so the group’s emphasis has been on connecting people with services. But a new nonprofit group in Fayetteville, Serve NWA, is stepping in. It recently got city planners’ approval to build several transitional shelters near the 7 Hills center to provide clients with a roof and basic services.

Sister Atkins said the region must come together to build and provide housing that’s affordable for the lowest incomes in particular. A grant that provided for Moore’s apartment deposit and similar help for nine other families ran out a while back.

“In Northwest Arkansas, there’s so many resources. We can end homelessness if we choose to,” she said. “We’re basically asking the community to intercede.”

Atkins and other advocates are also quick to add that relationships, support and other tangible services must accompany housing to help the new residents build their lives, as with Dean Vlaovich’s continuing relationship with Moore.

“You can’t just stick someone in an apartment and think they’re going to be OK,” Miller said.

Dan Holtmeyer can be reached at dholtmeyer@nwadg.com and on Twitter @NWADanH.