The Ouachita Mountains gave us True Grit, Lum & Abner, Dizzy Dean and Bill Clinton.

But the Ouachitas often get short shrift when compared with the overly analyzed Ozarks.

A Google search for "Ozark folklore" brings up thousands of websites, while a similar search for "Ouachita folklore" finds zero.

When Maj. Stephen Long made his map of Arkansas and Missouri in 1822, he left the Ouachitas out entirely. He had the Ozark Mountains stretching from the Red River on the Texas border, through Arkansas almost to St. Louis.

Ray Hanley, an Arkansas historian, said Harold Bell Wright's 1907 book The Shepherd of the Hills made the Ozarks popular nationally. It was made into a film in 1919, and there was another one in 1941 starring John Wayne.

The Ozarks were further cemented into the American psyche through Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip, which was published in newspapers across America from 1934-77.

Ouachita (pronounced wash-i-taw) is hard to say and spell, so Arkansans were probably happy to promote the more easily utterable Ozarks, Hanley said.

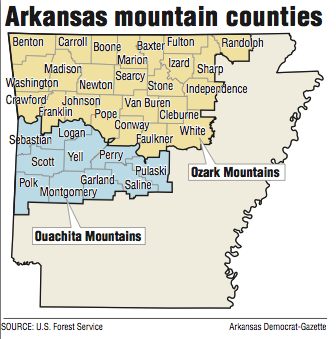

Generally divided by the Arkansas River, the distinctions between the two mountain ranges are a bit blurry. Part of the Ozark National Forest is south of the river, and some of the east-west ridges of the Ouachitas go north of the river, and all the way into Little Rock.

The Ozarks take up considerably more territory than the Ouachitas.

The Ozarks cover about 47,000 square miles, stretching across Missouri to the suburbs of St. Louis. It's the most extensive mountain range between the Appalachians and the Rockies.

The Ouachitas cover about 11,000 square miles. Together, the Ozarks and the Ouachitas make up what is known as the U.S. Interior Highlands.

The Ouachitas were caused by the collision of tectonic plates. The Ozarks are an eroded plateau that was shoved into an elevated position by the aforementioned collision.

"Eventually, continental collision ceased and the exposed, uplifted rock began to feel the effects of weathering and erosion," according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Then, about 200 million years ago, "South America tore away from North America and headed southward," according to the survey.

The Ozark Mountains also reach into Oklahoma, past Tahlequah, and even into the southeast corner of Kansas.

The Ouachita National Forest covers almost half of the Ouachita Mountains. The national forest consists of 1.8 million acres. Eighty percent of that land is in Arkansas.

Originally known as the Arkansas National Forest when it was established by President Theodore Roosevelt on Dec. 18, 1907, it became the Ouachita National Forest on April 29, 1926.

While the plateaus of the Ozarks were good for fruit orchards, farming was more of a hardscrabble endeavor for pioneers in the Ouachitas, according to a paper by Roger Coleman, archaeologist for the Ouachita National Forest. Many homesteaders who got 160 acres of Ouachita Mountain land for free abandoned it after one growing season. Much of that land now belongs to the U.S. Forest Service.

Academics don't all agree on whether the settlers of the Ozarks and the Ouachitas were basically the same immigrant groups. And, if not the same, did they have different European traditions that were passed down so that people in the Ozarks are now culturally different from their cousins in the Ouachitas?

Academics who feel that all Arkansas mountain folk are culturally the same are called "lumpers," said Brooks Blevins, an Ozarks expert and professor of history at Missouri State University. Those who believe they are different are called "splitters."

"I tend to be more of a lumper, though the whole enterprise is fraught with irony," Blevins said. "We need the splitters -- those who insist on high levels of regional distinctiveness -- to stay in business, even if lumping seems the more academically sound approach to regional studies."

Several authors contend that there is a Scots-Irish identity in the Appalachian Mountains and the Ozarks, and that has led to certain characteristics of middle-American mountain people.

But Blevins is skeptical.

"My point is that anyone who falls back on the Scots-Irish as the end-all-be-all for explaining Southern white culture is oversimplifying a complex process of cultural transmission and adaptation that takes place over many generations," he said.

Michael B. Dougan, scholar in residence at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro, noted that there are often distinct cultural differences from one Arkansas county to another, and sometimes within counties.

The people in Carroll County's dual county seats -- Eureka Springs and Berryville -- revel in their differences.

Eureka Springs is considered a bohemian artists colony and tourist town. It has always attracted residents from elsewhere, many of them from Chicago and New Orleans. Thirteen miles to the east, Berryville has a more homegrown Arkansas feeling.

The locals sum up this split personality with a joke of sorts: Carroll County, where Woodstock meets livestock.

Metro on 12/31/2017