At a Black History Month event recently, President Trump seemed to suggest that Frederick Douglass is still alive: He's "done an amazing job and is getting recognized more and more," Trump said. If he was referring to our awareness of Douglass' historical legacy, the president's remarks were on the money: More than 120 years after Douglass' death, the great abolitionist's impact on our country is still unfolding.

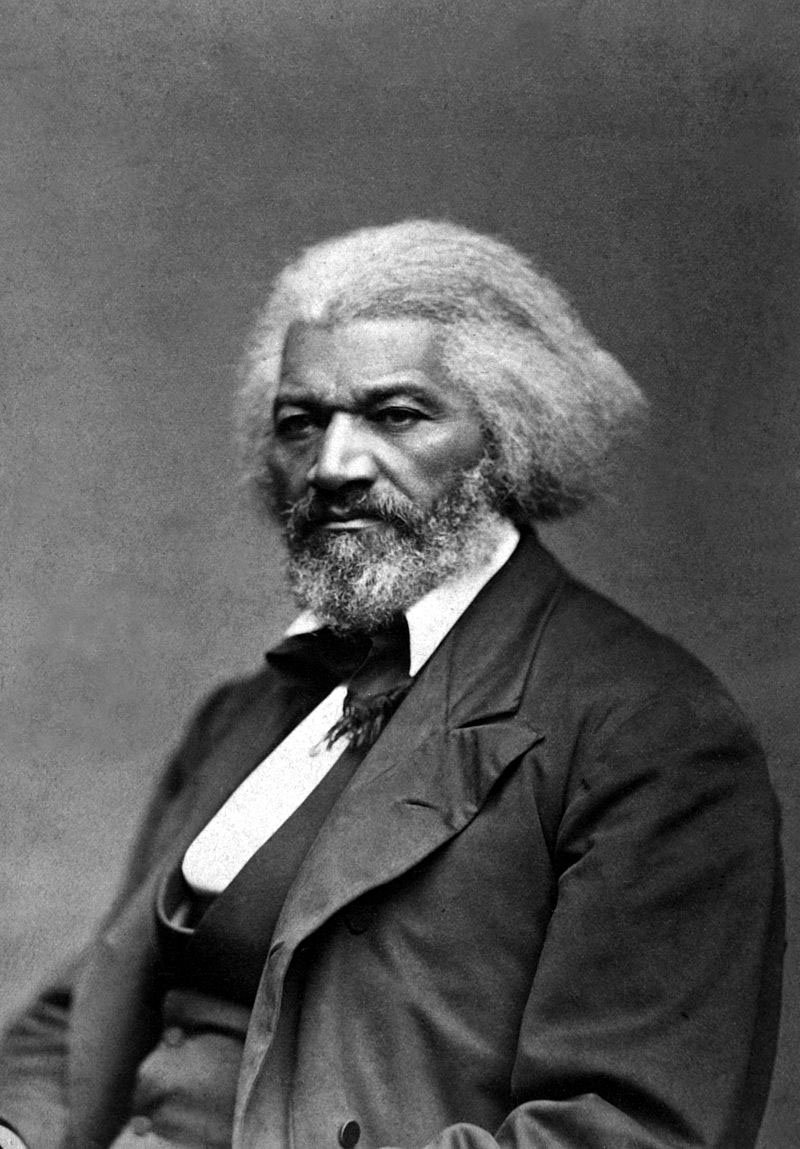

The former slave who became one of the nation's most widely read authors and most popular orators speaks to us through his prolific writings, and his legacy is ensured by his solid place in the literary canon and the treasure trove of images that he seemed determined to leave behind. But as Douglass' fame has grown, so too have misunderstandings about his history and personality. Here are some of them.

1.Frederick Douglass was an American patriot.

Douglass wanted blacks to fight for the Union in the Civil War, and after President Abraham Lincoln allowed them to serve, Douglass became the president's loyal supporter and friend. Following the war, Douglass became the first African American to receive a federal appointment that required Senate approval and was an official emissary to Haiti. It's no wonder that the Colored Republican Association of New York called Douglass "a patriot and a hero" upon his death in 1895 or that he is often listed in collections of American patriots. A monograph from the 1990s, for instance, was called "Frederick Douglass: Patriot and Activist."

Yet Douglass never defined himself as an American patriot; he was highly critical of the United States. In 1845, as a fugitive slave he fled to the British Isles for two years, almost settling permanently in England. For the first time in his life, he said, he experienced "an absence, a perfect absence, of everything like that disgusting hate with which we are pursued" in America. Only a sense of duty to his wife and his fellow African Americans and a desire to fight the scourge of racism and slavery, persuaded him to come back. "I have no love for America as such," he announced upon his return. "I have no patriotism. I have no country."

Sixteen years later on the eve of the Civil War, he planned a visit to Haiti to entertain permanent emigration to the black republic. "The North has never been able to stand against the power and purposes of the South," he concluded. If Haiti met his expectations as a "light of glorious promise," then he would remain in that country and call it home.

2.Frederick Douglass was a pious Christian.

Traditional Christian ministries such as the Colson Center claim that "Douglass was a committed Christian." Likewise, Christian publishing house Concordia includes Douglass in its Heroes of the Faith book series. And Douglass referred often to Christianity in his speeches and writing.

But his views on the religion were less than conventional. While a practicing member of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church for most of his adult life, Douglass used the Bible to interpret the North's role in the Civil War allegorically, with "Michael and his angels" battling "the infernal host of bad passions" in our country's version of the apocalypse. He frequently expressed his disgust at the fact that slave owners cited scripture to argue that slavery was divinely ordained and that the Lord demanded the docility of the enslaved.

In his final years Douglass became a Unitarian, a Christian denomination that does not recognize Jesus as divine and rejects many other traditional doctrines. His home contained artifacts and writings from several world religions as well as busts of his favorite philosophers Ludwig Feuerbach and David Friedrich Strauss, both of whom viewed Jesus as a moral person but not the son of God.

3.Frederick Douglass, a Republican, would fit in with today's GOP.

Contemporary Republicans, including the Frederick Douglass Republicans and the Oregon Republican Party, proudly remind us of Douglass's GOP membership. "The Republican Party is the ship and all else is the sea around us," Douglass said after the Civil War.

But his politics hardly resembled those of modern Republicans (just as Democrats of the time weren't like today's Democrats). In 1855 Douglass was a self-professed radical as a founding member of the Radical Abolition Party, which wanted to upend the status quo in the most dramatic way: immediate and universal emancipation, full suffrage for all Americans regardless of sex or skin color, the redistribution of land so that no one would be rich and no one poor, and violent interventions against slavery. Other founders included two of Douglass'sclose friends: militant abolitionist John Brown and James McCune Smith, the nation's first university-educated black physician.

During the Civil War Douglass became a Republican and remained a devoted member of the party for the rest of his life. At the time, the GOP--the party of Lincoln and Charles Sumner--consistently received enormous support from black voters and advocated a strong central government and certain entitlements for the underprivileged. It bears little resemblance to today's Republican Party.

4.Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery on foot.

Images accompanying descriptions of Douglass' flight from slavery (even period lithographs) often seem to depict him sneaking off through the wilderness. Many sources say simply that Douglass ran away, leaving readers to imagine him on foot, following the North Star to freedom, outracing bloodhounds and avoiding snakes and slave catchers in the swamps.

It's a dramatic notion, but Douglass' escape was more prosaic, mirroring many self-emancipations from the period that depended more on logistics and less on romance. Dressed in a sailor's suit (red shirt, black cravat and tarpaulin hat) and traveling under an assumed identity, Douglass boarded a train in Baltimore on Sept. 3, 1838. Then he took a steamboat from Wilmington, Del., to Philadelphia. Finally, he traveled via a night train to New York.

As soon as Douglass reached safety in New York he wrote his fiancee Anna Murray and asked her to join him at once. They were married Sept. 15 at the home of David Ruggles, a free black journalist, in a ceremony presided over by famous black abolitionist Rev. James Pennington, a newly ordained minister and, like Douglass, a fugitive from Maryland. On Ruggles' advice they moved to New Bedford, Mass., then the nation's whaling capital.

5.Frederick Douglass is "being recognized more and more."

Douglass was more famous in the 19th century than he is today. His first two autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845) and My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), were best-sellers. In addition he was one of the nation's greatest orators, a widely read journalist, and the most-photographed American of the 19th century--one of the most famous Americans of his time.

In the 1850s he was often compared in stature to Stephen Douglas, the Democratic leader who supported slavery, defeated Lincoln in the 1858 U.S. Senate race in Illinois and twice ran for president. Several journalists wanted "to have the black Douglass on the stump against the white Douglas." (The white Douglas, a virulent racist, hated the comparison.) Douglass was more famous than Lincoln until the 1860 presidential race; journalists sometimes misspelled the candidate's name as "Abram."

When Douglass died in 1895, thousands of tributes from the United States and abroad honored him. Collected in a 350-page book, they highlight his stature. The Washington Post began its tribute by saying, "Frederick Douglass was one of the great men of the century." And the Chicago Tribune declared: "No man, black or white, has been better known for nearly half a century in this country than Frederick Douglass."

Henry Louis Gates Jr. is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor at Harvard, where John Stauffer is Professor of English and African and African American Studies.

Editorial on 02/19/2017