It was around the middle of December 2015 when folklorist and author Robert Cochran of the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville was having lunch at the Capital Hotel in Little Rock with Bill Gatewood, Gail Stevens and Jo Ellen Maack of the Old State House Museum.

Cochran, of the university's Center for Arkansas and Regional Studies, Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences and a frequent guest curator at the museum, was pitching an idea for a new exhibit. When that idea didn't work out, he mentioned something else that might be better suited for the Old State House.

“True Faith, True Light The Devotional Art

of Ed Stilley”

Through March, 2018, Old State House Museum, 300 West Markham St., Little Rock

Admission: Free

(501) 324-9685

"Bob said, 'I just want to put a bug in your ear and I thought you might be interested,'" says Maack, the museum's curator.

He told the three of Ed Stilley, the preacher, sawmill worker and subsistence farmer from rugged, isolated Hogscald Hollow in Madison County who built guitars and other stringed instruments out of found parts and scrap wood and gave them away to children. Stilley, who had five children with his wife, Eliza, started making instruments in 1979, believing God had instructed him to do so, and finished more than 200 of the often ungainly, fascinating pieces before arthritis in his hands forced him to quit.

After the lunch "we sat in my office, the three of us, and said, 'We've got to do this,'" Maack recalls of the reaction she shared with museum director Gatewood and exhibit director Stevens.

The result is "True Faith, True Light, the Devotional Art of Ed Stilley," which opened Nov. 18 at the museum and runs through March 2018. Nearly 30 of Stilley's instruments -- guitars, mandolins and banjos -- are hanging at the museum along with a display of his tools, the crude wooden jig he used to bend instruments into their sometimes cockeyed shapes and a video featuring an interview with Stilley. There's even a Stilley guitar that visitors can play.

Arranged in chronological order and representing Stilley's early, middle and late periods, the instruments begin with a six-string banjo, the first piece he completed. Made of pine with a cooking pot nestled in the middle of its body that acts as a resonator, it looks like some sort of odd shop project.

Mirrors show the backs of some of the pieces and each instrument displayed is accompanied by an X-ray, taken by the Mocek Spine Clinic in Little Rock.

Stilley, who is wheelchair-bound now and lives with Eliza just off a highway a few miles from the hollow where he spent most of his life, found that placing items inside the bodies of his guitars helped with the sound, so

the X-rays reveal carefully placed springs, saw blades, glass medicine bottles and even the odd aerosol can -- Right Guard, in one case. For the saddle, where the strings sit on the bridge, he often fashioned bone from the family's supper scraps. The guitar frets are usually made of brazing rods used by welders.

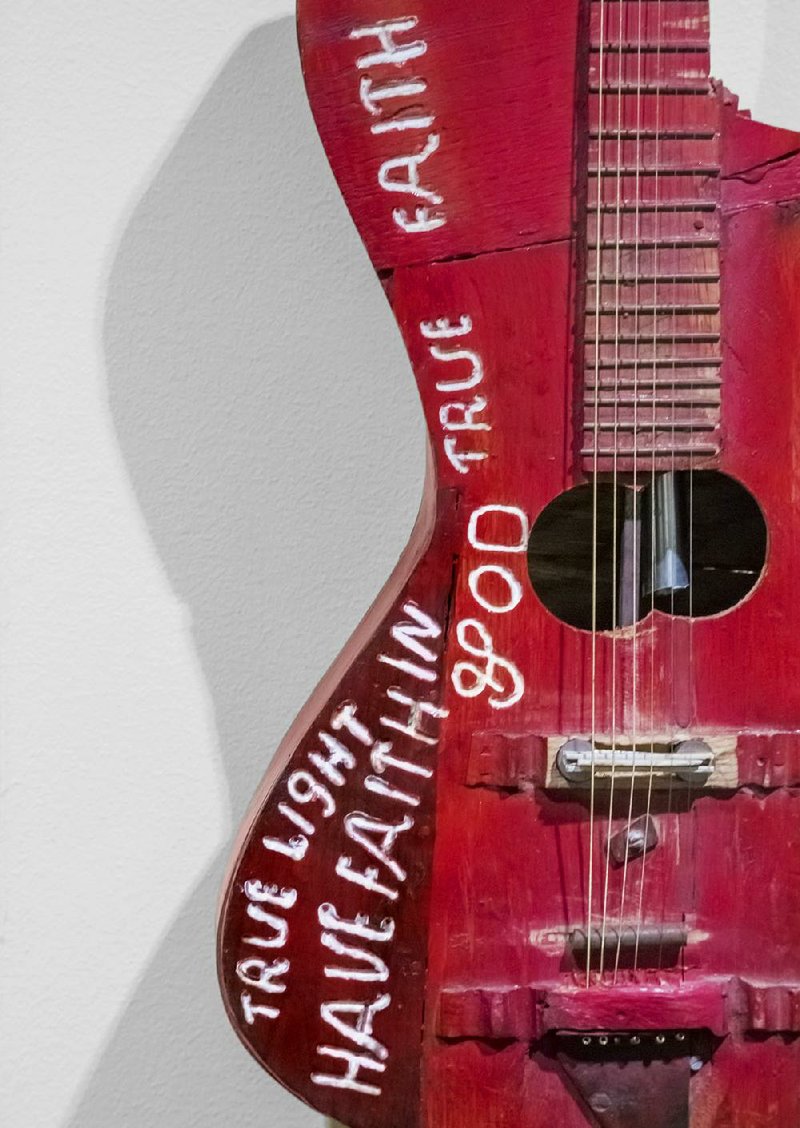

Stilley, completely self-taught and driven by his beliefs, made his instruments with simple tools, though once he got his hands on an electric router, he began scrawling "True Faith, True Light, Have Faith in God" on each piece.

"There was no tradition of vernacular instrument-making that he plugged into," says Cochran, author of, among other things, Our Own Sweet Sounds, A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas and co-author, with Suzanne McCray, of Lights! Camera! Arkansas!: From Broncho Billy to Billy Bob Thornton (which also inspired an Old State House Museum exhibit of the same title). "On the other hand, not only did he not learn from anybody who traditionally did it in that area, he didn't pass it down to anyone. He had no one following him."

Because he was working independently from tradition, the instruments are examples not so much of folk art but outsider art, Cochran says. Of course, academic distinctions of the genre his instruments belong to would be lost on Stilley.

"He doesn't think of it as art," Cochran says. "He thinks of it as [something] produced in obedience to a divine directive. The fact that he didn't know anything about [making instruments] was immaterial to him. He just started doing it and he figured that the Lord would be pleased."

Others were also pleased, including Fayetteville musicians Kelly and Donna Mulhollan, who actually play his instruments in their folk duo Still on the Hill.

...

"There would be no exhibit without Kelly and Donna," Maack says.

Kelly's gorgeous 2015 book on Stilley, published by the University of Arkansas Press with photos by Kirk Lanier and an introduction by Cochran, gives the exhibit its name and is a crucial document of Stilley's life and work.

Kelly Mulhollan first met Stilley in 1995. His wife, Donna, was visiting friends, Nina and Tom Luther, who had been neighbors of the Stilleys in the '70s and had received a guitar from Ed. Donna knew her folk-art-loving husband would appreciate the strange piece.

"She ran home to me and said, 'You've got to see this to believe it,'" Kelly recalls.

The Mulhollans were smitten.

"From the very start, we both felt like we had stumbled into one of the great folk artists of our time," Kelly says. They asked the Luthers if they would introduce them to Stilley and a friendship soon grew.

"We both started visiting -- especially me -- regularly, and watched him work," says Kelly who, with Donna, is a guest curator of the Little Rock exhibition.

Going to Hogscald Hollow, where the Stilleys didn't get electricity until the early '60s, was like taking a trip back in time.

"There were very few signs the 20th century had marched on at all," Kelly says. "The first thing you encountered in the front yard was a sorghum press with a big turnstile that would be run by a mule."

The property was filled with "an incredible collection of rambling buildings made of scraps," all built by Stilley, Kelly says.

Kelly eventually began thinking of writing a book about his friend.

"The book meandered into existence over a period of about five years," Kelly says. "I'd been dreaming about a book and trying to take some pictures, but not being a photographer or an author was a huge obstacle for me."

A 2013 exhibit of Stilley-made guitars at Walton Arts Center in Fayetteville, in association with the Fayetteville Roots Festival, attracted Cochran.

"He was astounded when he walked in," Kelly says of the professor's reaction at the exhibit. "He realized that this needed to go further. He marched over to the University of Arkansas Press and made it happen."

"Kelly had already done all the work," Cochran says. "I just got the parties together."

Along with Lanier's photos, the book also includes black and white images taken in 1997 by then Rogers Morning News photographer and current Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette's outdoors editor Flip Putthoff, several of which are featured in the Little Rock exhibit.

"That one is my favorite," Maack says of a large reproduction of a Putthoff photo showing Stilley lining up several of his instruments along the rear bumper of an old car at Hogscald Hollow.

...

The Mulhollans play a guitar and fiddle given to them by Stilley when they perform. Kelly's dramatic "butterfly" guitar is perhaps the most striking of Stilley's creations.

"They're all different," Kelly says of playing one. Frets are oddly spaced -- "pretty approximate" in Kelly's words -- the heavy scrap wood isn't typical of a normal acoustic guitar and the strings are often high off the neck, making chords hard to form.

Still, "Each instrument has its own intonation, its own signature, which I like. If you put it in the hands of a good player, they will let the instrument lead them toward what it wants to do."

When other guitarists try his butterfly six-string, they are often surprised, he says.

"I've had it at festivals and a good guitar player would play it and say, 'Just let me be alone with it for an hour and let me play it,'" he says with a chuckle.

Stilley's work hanging on the walls of the Old State House Museum is another step in getting the Ozarks artist's work out into the world, Kelly says.

"Even though Ed has had no need for recognition, Donna and I have felt this pull, that this is simply too important not to be seen. Putting it in the State House Museum, the finest historical museum in the state of Arkansas, and for them to have done such an exquisite job, it feels like the complete fulfillment of a dream."

"We all knew this exhibit was going to be phenomenal," Maack says, as a group of schoolchildren from Warren inspect the rough beauty of Ed Stilley's inspired vision, "and it has been."

Style on 01/01/2017