A year ago I woke in the night with pain so severe I was crying before I was fully aware what was going on. A 50-year-old cop sobbed like a child in the dark.

It was a ruptured disc and related nerve damage. Within a couple of months, it became so severe that I could no longer walk or stand. An MRI later, my surgeon soothingly told me it would all be OK. He would take care of me; the pain would end.

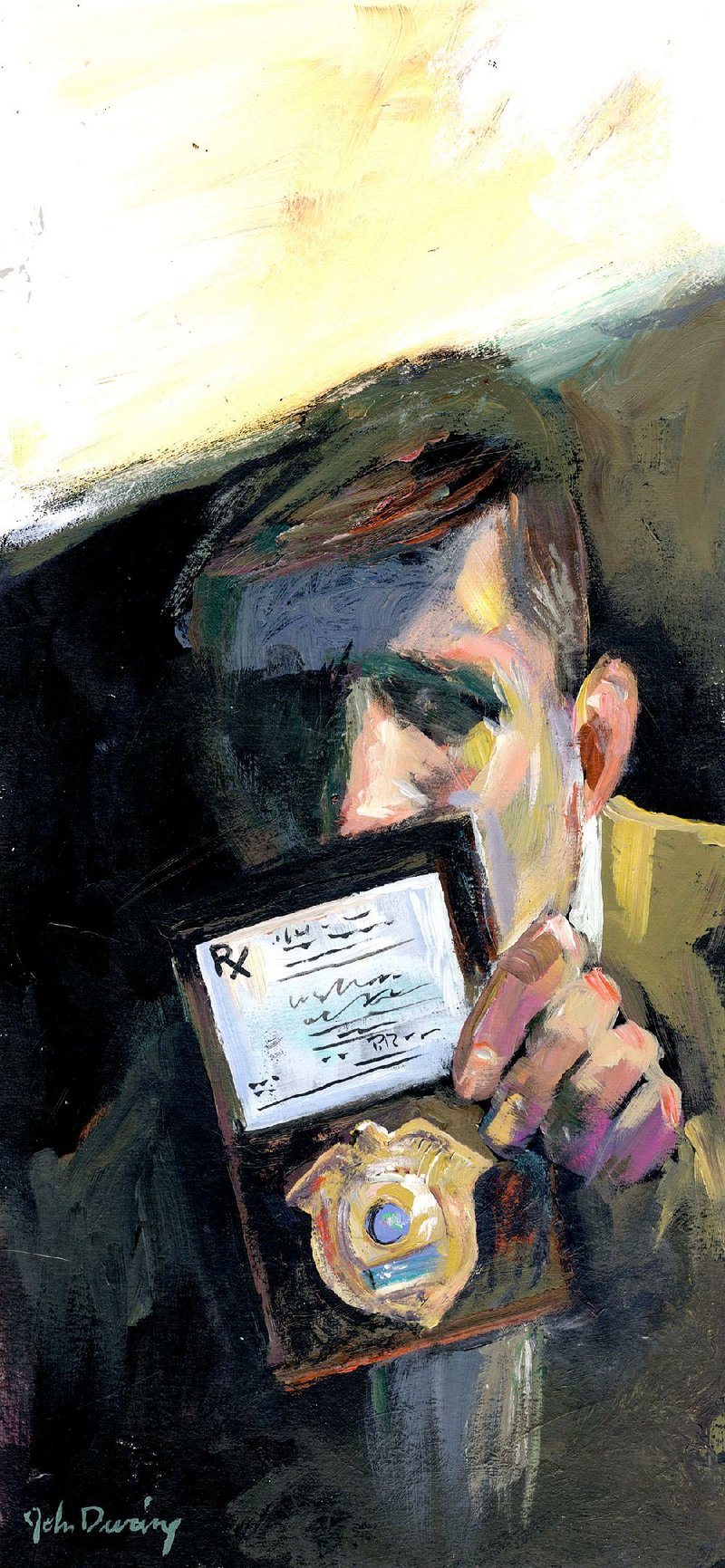

After surgery, I never saw that surgeon again. A nurse practitioner handed me a prescription for painkillers--90 each of oxycodone and hydrocodone.

I was lucky: I already knew how easily opioid addiction could destroy a life. I'd arrested addicts and helped people suffering from substance abuse. So as soon as I could, I weaned myself off the medication. Still, I fell into the trap when my pain returned months later, and I started taking the pills again.

Since then I've been stuck like a growing number of people in a system that leaves patients beholden to terrible health policy, the horrific consequences of federal drug policy, uninformed media hysteria

about an opioid epidemic and an army of uncoordinated medical professionals bearing--then seizing--bottles of pills.

I asked repeatedly for alternatives, but was told none were available. I started physical therapy and sought treatment at an authorized pain management clinic. My first pain management doctor was terse as she prescribed more hydrocodone for daytime and oxycodone for the night, when my pain was worse. To her, I was just another person in a day of people receiving identical treatment. Later she'd say she had little choice: Insurance companies routinely deny even slightly adventurous prescriptions.

A nearby chain pharmacy refused to fill it, saying, "You can't mix hydrocodone and oxycodone." As my prescription testified, I was receiving the required "close monitoring" by a doctor when taking that particular combination. When I called the pain clinic for help, the staff berated me for bothering them. They asked whether I was seeking drugs. I was--the ones they had prescribed.

As a police officer, the only thing new to me about the opioid epidemic was being physically dependent on them. I've seen it among people in jail and people about to go to jail. Often, while searching cars or people, we find pill bottles containing several types of opioids, almost always stolen or bought illegally. Police departments around the country are ordering the opioid counteragent naloxone in increasing quantities, but Narcan can't keep up with the demand on the street.

Meanwhile, the Associated Press and the Center for Public Integrity reported that drug companies and advocates for drugs such as OxyContin, Fentanyl and Vicodin spent more than $880 million on lobbying and political contributions at the state and federal level over the past decade, compared to $4 million by groups advocating for opioid limits.

My insurance company paid for eight physical therapy sessions and refused more. They'll pay for buckets of Vicodin. But non-narcotic relief? I'm on my own.

Then they declined the Buprenorphine my doctor prescribed, which had been helping for pain and not making me drowsy or euphoric. Instead, they'd pay for Fentanyl, the much stronger synthetic opioid that's making cops sick just by being in the same room with it. I wouldn't risk taking it. It took two months, three dispute letters and more than $700 out-of-pocket before they'd recognize my doctor might actually know what to prescribe me.

Now, like so many other Americans, I find myself in a medical twilight zone where distrust outweighs care, where doctors fear censure and pass me off to another office.

My life is filled with indignities large and small. Due to standard pain patient's contracts, like virtually all patients at pain clinics I'm subject to urine tests to determine whether I've taken anything other than the opioids I've been prescribed. Every month when I try to get my prescriptions filled it becomes another skirmish in the war on drugs. Besides testing, there are other demeaning conditions such as bringing all my pill bottles, like a schoolboy, so the nurse can count the remaining pills during each clinic visit. There are specific times at which refills will be given, without exception. If my transdermal patch falls off during the month, which isn't uncommon, getting an early refill is a complicated hassle.

The same contract states that if the patient becomes addicted to these medications--which are addictive when taken as directed--the clinic "will help you get treatment and get off the medications that are causing you problems safely, without getting sick."

Yet that treatment does nothing to help the pain that led to the use of the addictive drugs on doctor's orders in the first place. In fact, it says that the "medicine may not be replaced if it is lost, stolen, or used up sooner than prescribed," but the only solution offered to patients with pain is to take more of it.

Doctors have become so concerned with censure for over-prescribing, and so handcuffed in what they prescribe, that the cycle is almost guaranteed to lead to exquisite patient frustration if not addiction.

For some pain patients the challenges are so great that they have given up. They turn to the street for their pain relief, where the drugs are cheaper and easier to obtain. How easy? In 2015, 312,000 kids between 12 and 17 bought painkillers from friends or family. After four decades of all-out war on illicit drug use, scoring street heroin is still far simpler than filling a legal prescription at an authorized dispensary.

How can this be considered a success?

America's drug policies are having deadly effects. Americans comprise less than 5 percent of the world's populace but consume 80 percent of the world's opioids and 99 percent of the world's hydrocodone. The hydrocodone tablets found in Prince's house the night he fatally overdosed were counterfeit. Those pills, with the same markings as some of mine, tested positive for Fentanyl, the drug United Healthcare wanted me to take.

I've read that Prince suffered from some of the same pain I did. But as a cop it's even more complex. I need to be extra careful not to dull my senses because I must be able to testify under oath that I wasn't impaired. I must in fact always actually not be impaired, because I carry a gun.

It had come to the point that I had begun to consider quitting police work. Then I visited Robert Semlear, a family medicine practitioner. I'm working in New York, and I thought I was seeing him on something unrelated. He looked at my chart and said, "OK, the first thing we're doing is getting you off these opioids." I hadn't even said anything.

I told him I was in a lot of pain. He said we'd start a plan to wean me off and find the right combination of medicine, exercise and physical therapy to keep me off opioids for good.

It's early, but this seems to be working. I've started (for the second time) the opioid wean and am seeking treatment from a specialist to handle issues related to the physical dependence.

How can it be that, in the name of health we moved away from demanding our doctors do more than just hand out pills? Where is the exploration for new therapies to help for pain? In Germany doctors prescribe warm mud packs and massage. Acupuncture is used in many countries with great success. In 28 states and the District of Columbia, medicinal marijuana is now legal, but the federal government still bans it.

Almost anything is better than what we are doing now.

As a cop I'm not free to even consider marijuana, which effectively managed my father's pain and nausea when he was dying of cancer. Even if it were legal in my state--it is not--it would still be against department policy. In addition to my doctors' drug tests, I'm also subject to drug testing on the job. Which means something I believe truly is effective against pain and has fewer side effects than opioids is not available to me.

When I was 14, I read Eugene O'Neill's classic play Long Day's Journey Into Night. Set in 1912, it opens with a mother just out of rehab from the morphine her doctor prescribed. If you've read it, you'll remember the play doesn't end well.

Can it be possible that American medicine has been running in place for more than a century?

I don't think so, either.

Nick Selby is a Texas police detective and the lead author of In Context: Understanding Police Killings of Unarmed Civilians.

Editorial on 01/22/2017