"You know what the public's really like; they're a cage full of guinea pigs. I could feed them dog food and they'll think it's steak. Good night, you stupid idiots."

-- Lonesome Rhodes, A Face in the Crowd

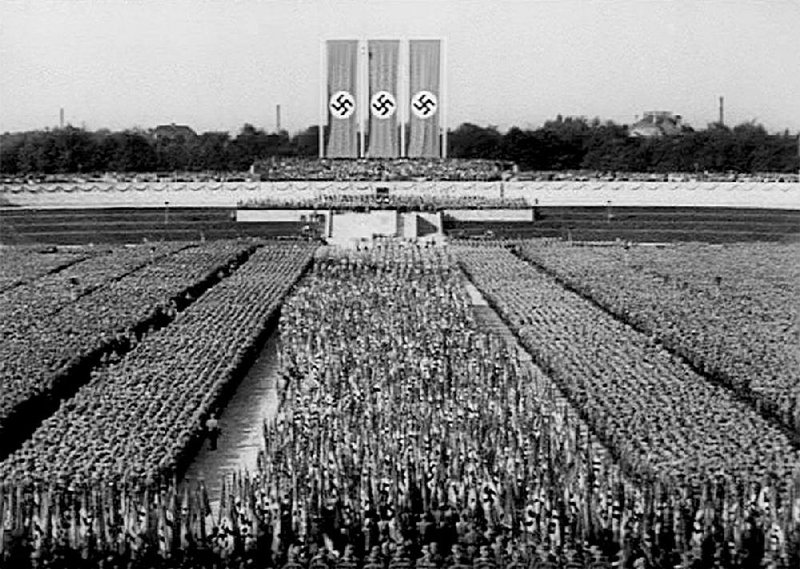

A decade or so ago I taught a class called Movies and Politics for a local university. We started out with Leni Riefenstahl's 1935 film Triumph of the Will, which drew mixed reviews from the upperclassmen who'd signed up for the class. Many of them had trouble getting past the black-and-white cinematography. A lot of them had trouble seeing how it could possibly have anything to do with their lives.

The moment I remember most about that class came just before the lights went out and the VCR (it was that long ago) clunked into action, when I asked my students to consider what had been going on in Europe in the '30s. At first there was no response, but finally a young man raised his hand and asked tentatively: "The Civil War?"

To be fair, college students generally give the answers they think their professors want to hear. They compartmentalize each class and it's only later -- if ever -- that they begin to make connections and glue the discrete pieces of their education into a coherent worldview. They thought we were going to watch movies, and most of them had their ideas about what movies were and what they weren't. And their movies didn't ask them to think about Weimar Republic politics or global depressions. Their movies were populated by action figures with uncluttered motivations.

It was interesting to watch them watch the film. Triumph of the Will is a film you feel like you've seen even if you've never committed yourself to watching it. Over the years, bits and pieces of it have lodged like shrapnel in the collective imagination; clips show up in just about every documentary made about the rise of Adolf Hitler. If you've an idea what a phrase like "fascist architecture" might mean, then it's likely you're drawing from the store of monochromatic images framed by Riefenstahl.

This "documentary" of the 1934 Nazi party congress in Nuremberg has been called the greatest propaganda film of all time. To shoot it, Riefenstahl constructed dozens of ramps, bridges and towers in the city. Along Adolf Hitler Square a ramp was built that rose to second-story level in order that Riefenstahl's cameras might dolly along above the marching storm troopers, photographing them from a birds'-eye view. A camera was installed in an elevator attached to a 120-foot flagpole at the Luitpoldhain, the parade ground where Hitler would address his Brownshirts.

Riefenstahl's corps of cameramen were dressed in elite SS uniforms to intimidate and ensure their actions would not be questioned by either officious bureaucrats or the rank and file. Wooden tracks were laid so that the cameras could move between rows of troops. She commandeered fire trucks and construction cranes and even put some of her cameramen on roller skates. In all, she shot more than 61 hours of film over the course of the six-day rally, and spent months editing it down to just under two hours.

While there is a faux Wagnerian score, there is no spoken commentary in the film. Riefenstahl considered voice-overs "the enemy of film" and left all verbalization to Hitler and other Nazi leaders. Riefenstahl did not invent or make any attempt to influence the actions of any of the people she photographed. Instead she choreographed the images and sounds. She worked with marching men and swastikas, banners and eagles, with Teutonic folk songs and oratory. She made a mad, solemn, chilling film that manages to be -- sometimes in almost the same moment -- tedious and fascinating, awesome and terrible.

...

As Triumph of the Will was inspiring moviegoers in Europe -- it won a gold medal at the 1935 Venice Biennale although the Nazis didn't make a serious effort to promote it outside of Germany -- Sinclair Lewis' novel It Can't Happen Here was published, a book inspired by the rise of Huey P. Long who was preparing to challenge Franklin D. Roosevelt for the White House in 1936 (Long was assassinated in September 1935).

It Can't Happen Here presents the story of Sen. Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip, a populist Democrat, who becomes president in the late 1930s on a platform that claims to speak for "Forgotten Men," championing a redistributionist platform similar to Long's proposed "Share the Wealth" program. (Long was also the model for Willie Stark, the protagonist of Robert Penn Warren's All the King's Men, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1947.)

Some people will tell you they want art to provide them a respite from politics; others will point out that every choice is political. Movies are assembled by people with points of view. And while all that ultimately matters to the market is whether you buy a ticket, it's interesting to note how artists interact with politics. Americans have been warned that it -- whatever you imagine "it" to be -- can happen here throughout our history.

In 1972 director Michael Ritchie and movie star Robert Redford collaborated on a savvy, keenly observed political satire called The Candidate. In that film, Redford played an idealistic young politician who's free to run his campaign for the U.S. Senate with reckless integrity because of the almost absolute certainty he will lose. Only he doesn't lose and the movie ends on a particularly unsettling note as the euphoria of Redford's character's unexpected victory is interrupted by an aide asking, "What will we do now?"

In 1998 director and movie star Warren Beatty provided the answer with his brilliant satire Bulworth: You grow corrupt and crazy.

...

On Jan. 20, the cable television network TCM (Turner Classic Movies) programmed another movie I used to show in my class: Elia Kazan's 1957 A Face in the Crowd starring Andy Griffith as Lonesome Rhodes, a folk-singing drifter who becomes a populist celebrity and ends up a powerful megalomaniac eventually undone by a spurned woman (Patricia Neal) and a hot microphone.

TCM's timing seemed suspicious, since it's not hard to draw parallels between the ascension of former reality TV star Donald Trump to the White House and Rhodes' character arc. (Though Trump weathered his hot microphone moment.) But the network explained it wasn't trolling the new president. The decision to air A Face in the Crowd (which I am required by statute to remind you was filmed largely in Piggott because Ernest Hemingway associate Otto "Toby" Bruce recommended the location to screenwriter Budd Schulberg) had been made long before Trump won election on Nov. 8. It was part of a birthday celebration of A Face in the Crowd co-star Neal, born on Jan. 20, 1926.

At least that's the story they're going with.

...

Having seen the film a few times, I have some ambivalence about it. Griffith is remarkable, and anyone who only knows him through his amiable performances as Sheriff Andy Taylor or lawyer Matlock may be surprised by the depth and darkness of his character. Neal is also superb.

But the script is a little too pat -- as The New York Times' Bosley Crowther observed in a contemporary review, "so hypnotized are they by his presence" -- and his undoing feels more like a function of changing fashion than a fundamental repudiation of his rhetoric. I get the feeling that Kazan and Schulberg had almost as much contempt for their audience as Rhodes had for the yokels who uncritically embraced him.

I've always preferred Tim Robbins' 1992 film Bob Roberts, which feels in some ways like a covert remake of A Face in the Crowd with a blacker ending. In that movie, Robbins plays a folksinging right-wing senatorial candidate -- a hybrid of Woody Guthrie and Wall Street's Gordon Gekko -- who operates a financial brokerage firm out of his campaign bus.

One of the most interesting things about the film was the soundtrack. Robbins and his composer brother David, crafted a number of songs inverting the sensibilities of Bob Dylan ("The Times Are Changin' Back") and Guthrie ("This Land Is My Land") for the film. Robbins elected not to release a soundtrack album for fear they would be co-opted by conservatives.

It has been said if you want to understand liberal American politics, watch The Candidate and Bulworth. If you want to understand conservative American politics, watch Bob Roberts.

...

Some of us use movies as a respite from the workaday world. Ask a typical moviegoer why he subscribes to his drug of choice and more often than not he'll say something about wanting to "escape." A giant industry has grown up to transport rooms of people to alternate realities for a couple of hours at a time. Movies are about entertainment, a kind of passive recreation that allows us to voluntarily submit to the flickering commercial visions of dream retailers. One pays good money to be removed from the realm of one's troubles.

Yet it is also true that every movie is an advertisement for something, for a way of looking at the world or for the leading actor's favorite brand of cigarettes. Movies sell products and ideas, and while accidents certainly happen, nothing that occurs within the boundaries of the frame should be taken as randomly selected. Movies are not real life but arrangements of light and sound, illusions projected on the wall and assembled in the mind of the watcher. An unwatched movie is an uncompleted work -- as receivers of the signal we are all collaborators in the process. The audience performs a function analogous to the top of a guitar; it works as a sounding board, amplifying and coloring, turning so much excited air into a recognizable tone.

The problem is that the American mind has been vulgarized to a shocking degree. A lot of us have genuine problems recognizing the subtleties inherent in human endeavor. It is not impossible for a Riefenstahl to make a film that is great and horrible, for an Oliver Stone to make a movie that is historically inaccurate -- loaded with what we might call "alternative facts" -- yet profoundly "true." We've given up on the old ways of reading novels and poetry. We've become so literal-minded that we can't reconcile ourselves to the idea that good fiction is inherently more honest than what passes for journalism.

A journalist faces epistemological limits. The more honest the journalist, the less he is able to pretend to know. The artist is free to create fictions that suggest the deeper movements of the heart. The author is god of his universe, and while even a god can't know his own motives, we can trust what he puts on the page.

Because market forces will always convert the movies to, at best, infotainment, we ought to be particularly suspicious of movies that purport to tell the truth about anything.

Maybe my students had the right idea.

Tightly choreographed and beautifully photographed, a product of fascist discipline with practically no narration to lead our thinking, Triumph of the Will shows rather than tells. And it is possible to regard it as a formal masterpiece. You have to know context to recognize it as a monstrosity of misplaced talent.

Watch it in a vacuum, the horror vanishes. My students probably thought of it as just another obstacle placed in their way as they strove toward a credential that they hoped would someday mean more money in their pockets. A few let their annoyance show. A couple feigned interest.

I'm not sure any of them thought it has anything to do with them.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 01/29/2017