First in a series

Over her short life, Avah Forrester's eyes turned from gray to blue to brown, same as her brother Alex.

She was just starting to smile. Her parents captured them on a single video, 9 seconds long.

"I watch that video over and over again," says Avah's mother.

The 10-week-old normally slept in a crib in the family's Jacksonville apartment, on her back, her parents say.

Then one December night, her mother was in bed breast-feeding Avah. More tired than she realized, she fell asleep. When she reached for her baby a few hours later, Avah was wet, limp and cold.

Sobbing in her father's lap that day, Avah's mother, Jessica Milum, cried: "What did I do for God to tease me, to give me this precious baby and then take her away?"

A year later, Alex, now 4, still asks: "Where is my baby sister?"

Full coverage + online extras

Day 3:

- Stopping killer of babies takes money; how Arkansas, others try to curb sleep deaths

- How babies die sleeping: Details from a few cases

Day 2:

- Parents can face charges; unsafe sleep deaths sometimes a crime

- How babies die sleeping: Details from a few cases

Day 1:

[DEAD ASLEEP: Babies at Risk » Full coverage + tips for safe sleep, interactive quiz, more]

Avah Mae Forrester died Dec. 30, 2015, one of more than 1,000 infants in Arkansas since 1999 who appeared to be healthy when they went to sleep, then never woke up.

Most died in surroundings that experts say were unsafe for babies less than a year old.

In the U.S. and Arkansas, sleep deaths claim more babies between the ages of 1 month to 1 year than any other cause, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That includes birth defects, premature births, vehicle crashes and assaults.

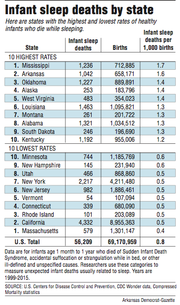

Arkansas has a higher rate of infant sleep deaths than 48 other states.

Between 1999 and 2015, Arkansas lost 1.6 infants in sleep-related deaths per 1,000 live births, according to CDC data. Only Mississippi's rate is higher. The national average is 0.8.

Those decimal points signify lives. If Arkansas' rate matched the nation's, about 500 babies here would still be alive.

The key to saving those lives, researchers increasingly believe, is placing infants to sleep -- every time -- in a safe manner. That means on their backs; alone; in approved, bare cribs or playpens; without pillows, blankets or other clutter.

Research shows that about 85 percent of infants who die in their sleep are found in what experts say are unsafe positions or surroundings that can stress and jeopardize their breathing.

"Arkansas does have a significant problem" with infant sleep deaths, says Dr. Whit Hall, a pediatrics professor and researcher at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. "But we think safe sleep can prevent a number of those deaths.

"We have to educate people to do everything possible."

An Arkansas Democrat-Gazette review of 102 cases of infant sleep deaths in the state since 2010 found that 90 percent occurred in high-risk sleep surroundings.

The newspaper's information came from coroners' reports from Pulaski, Benton, Faulkner and Sebastian counties. Among the findings are:

• Almost half were sleeping beside at least one other adult or child. One 3-month-old was in bed with five other people: his mother and four siblings, ages 2-7. Most, however, were sleeping with one adult.

• More than 40 percent of the victims, or four in 10, were lying facedown or on their sides. Research shows that both positions are risky for sleeping infants.

• About one-third were on adult beds, often on soft mattresses with blankets and pillows.

County coroners' reports in 75 percent of cases identified two or more risk factors, the newspaper's review found.

While low-income, less-educated, black and American Indian families have higher risks of infant sleep deaths, no household is exempt from them, the coroners' reports show.

A baby sitter placed one Little Rock infant on his side in a playpen that was considered safe. He was found dead lying facedown. His mother was a physician in training at UAMS.

Another infant died while sleeping on the chest of his mother, who was sitting on a couch at a Little Rock homeless shelter.

At least two babies in the newspaper's survey died facedown or on their sides at licensed or home-operated day cares.

Research also has found that infants who live in homes with smokers have higher risks of sleep deaths. Overheating with heavy clothing and too-warm temperatures is another danger. Any recent respiratory infections also raise an infant's risk.

"You wouldn't want parents to put their children in a car without a seat belt," said Hall, the UAMS pediatrics professor. "But actually, the most important thing they can do is put their babies on their backs in a safe crib.

"The next thing is, don't smoke around their babies," he continued. "The next is, don't put their baby in the same bed with them.

"The last important thing is to breast-feed," Hall said. Breast-feeding lowers the risk for infant sleep death, although experts aren't sure why.

'She's not breathing!'

When Avah was born at UAMS, her father, Adam Forrester, got to cut the umbilical cord.

"It was probably the coolest thing I've done, ever," he said.

She smelled of "spit-up and baby lotion. A sweet and tart combination," her mother said.

"Lavender anything" is the scent Forrester recalls.

Avah's parents, both age 26, agreed to talk about their daughter, about the night she died and about the months since in hopes of helping others.

"My nurse-practitioner said it might help someone else to know that you can't get over it, but you can get through it," Avah's mother said. "Even if one person reads it and it helps them, it's worth it."

The couple talked like a tag team -- him, her; him, her -- throughout interviews at their home.

Avah's time was so short, Forrester said, that she seems like a dream.

"It's OK to talk about her," Milum said. "Talking about her makes me feel she was real."

Milum had worked in day care and learned about safe sleeping recommendations. At UAMS, when Avah was born, the guidelines were discussed again.

That's why, Milum said, Avah slept in her bassinet every night, with no blankets, no toys and a tight sheet -- everything safe-sleep guidelines recommend.

Then, late on the night of Dec. 29, 2015, Milum was coloring her hair. A timer sounded right before midnight, and the baby woke up crying.

Milum took Avah into her arms to nurse and climbed into bed beside her fiance.

Milum was tired. She thinks she fell asleep about 1:15 a.m. Sometime during the night, Avah's brother, Alex, joined them in bed and slept at their feet.

Milum awoke more than five hours later, at 6:41 a.m. She remembers the exact time because she glanced at her cellphone.

Avah lay on her back to her mother's right.

"When I picked her up, she was freezing and kind of stiff. Her little head kind of fell," Milum remembers.

The parents started CPR. Frantic, they phoned 911.

"We kept screaming at the 911 operator," Milum said. "She's not breathing! She's not breathing!"

At 6:46 a.m., Jacksonville police and paramedics arrived at the family's 44 Georgeann Drive apartment.

Medics grabbed up the infant in her blue snowman blanket and ran to the ambulance.

"It can't be real," Milum remembers thinking. "I expected those paramedics to come back and say, 'Mom, you're crazy, Avah is all right.'"

A little while later, Forrester said, three or four rescue workers walked back to the house. Their heads hung down.

"I fell on the floor, screaming," Milum said.

Risk factors

Not so long ago, scientists considered infant sleep deaths among medicine's greatest mysteries.

Even by the early 1990s, researchers knew little about risks or preventions for the killer known as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

Scientists described the deaths with words like inexplicable, unpreventable, natural.

These days, Dr. Mary Aitken, director of the Injury Prevention Center at Arkansas Children's Hospital, follows the lead of most national researchers who use a different description:

Preventable.

"Were many of these deaths preventable?" Aitken said in a recent interview. "Frequently, yes. That's not to be punitive and labeling with parents or anyone. It's trying to prevent tragedies like these in the future."

In recent years, most scientists have subscribed to a "triple-risk" model in trying to understand infant sleep deaths that can't be explained through autopsy and investigation.

According to the National Institutes of Health in Maryland, the model suggests that the infant victims must have all three of these risk factors:

• A physical defect or vulnerability, perhaps an underlying brain abnormality, which science is still working to identify. Many scientists say the problem may prevent these babies from rousing from sleep or turning their heads if oxygen levels drop.

• A "critical development period" of rapid growth, which usually comes between 2 and 6 months of age.

• Being placed in a sleep situation that can put stress on an infant's breathing. Stressors include sleeping facedown or on a side; co-sleeping with adults or other children; proximity to soft objects such as pillows, blankets and crib bumpers; cigarette smoke; and overheating.

"Although these stressors are not believed to single-handedly cause infant death," a National Institutes of Health report says, "they may tip the balance against a vulnerable infant's chances of survival."

That's where safe sleeping measures are critical, experts say.

"We may not be able to identify the most vulnerable babies" who have all three risks, Aitken said. Safe sleeping recommendations are an effort "to get at what we can control."

According to the National Institutes of Health: "If caregivers can remove one or more outside stressors, such as placing an infant to sleep on his or her back instead of on the stomach, they can reduce the risk of SIDS."

In 1994, public health groups started a national Back to Sleep campaign emphasizing the importance of babies sleeping on their backs. In the next 10 years, the infant sleep-death rate dropped by 50 percent nationwide. The rate has remained steady since.

'Thank you, Jesus'

The Pulaski County coroner's office was notified at 7:53 a.m. the day Avah died.

Coroner's office investigator James Solis went to the apartment and found Jacksonville detective Ben Pace and other officers already there.

Avah was in the ambulance, lying on her back on a stretcher.

"Detective Pace advised that the decedent was found unresponsive in bed with the mother, father and brother," according to Solis' report. "The mother had fallen asleep with the baby still in her arms."

Solis examined the baby and took photographs. He described her as coroners typically do for healthy infants: "well-developed, well-nourished."

Her head, face, neck, chest, abdomen, lower extremities, upper extremities and back all were "noted to not have any obvious injuries or deformities." The baby was placed in an infant body bag.

Solis entered the family's apartment and took more photographs.

"This office then interviewed the decedent's father," the coroner's report said.

The mother "was unable to answer any questions at this time."

The body was sent to the state Crime Laboratory in Little Rock for autopsy. Police interrogations began the next day.

In the police report and in interviews, Avah's parents described her as being a bit fussier than usual the night she died. She had a low-grade fever, and they gave her Tylenol.

Also, Avah had spent three nights in Arkansas Children's Hospital about a month earlier suffering from bronchiolitis. A Dec. 22 checkup showed her to be fine, Milum said, and the baby got her six-week shots and an inhaler, just in case. Milum said the baby never needed to use the inhaler.

Police asked the mother and father: Did you choke her? Did you shake her? Did you roll over on her?

No, they answered.

Milum said she started remembering more about how she had drifted off to sleep with Avah between her and Forrester.

"I freaked out, I lost it -- I caused it," she thought.

In a heart-wrenching moment with detective Pace, recorded on video by law enforcement officers on Dec. 31, 2015, a weeping Milum asks: "Is this my fault?"

Pace responded, his hand over hers: "No, ma'am."

Fifteen years ago in Arkansas, a coroner's office and law enforcement agencies would have carried out little or no follow-up investigation in a death like Avah's, says Faulkner County Coroner Patrick Moore, who teaches courses in infant-death scene investigation.

Those sleep tragedies were considered to be of natural causes and unpreventable. Unless someone suspected foul play, there was little more to investigate.

But since about 2006, national and state authorities have stepped up death-scene investigations regarding babies who die in their sleep. One reason is to help researchers try to find ways to prevent such deaths.

In Arkansas, most county coroner's offices, as well as many law enforcement agencies, have received training in sudden, infant death investigations, Moore said.

In some jurisdictions, including Pulaski and Faulkner counties, investigators ask parents to use a doll and re-enact what happened to their baby. That's the national recommendation and part of Arkansas coroner training. But it doesn't always happen.

Milum and Forrester said investigators didn't ask them to re-enact Avah's death.

"They did not, thank you, Jesus," Milum said. "That would have been hard."

'Standing in quicksand'

Avah's parents never spent another night in the house on Georgeann Drive.

They immediately moved in with a friend in North Little Rock who had a two-story house with enough space for Milum, Forrester and Alex.

Then came the funeral, more grief and the people who meant well when they spoke.

That time felt like "trying to think through Jello. You have to push every thought out through your mouth," Forrester said.

Avah was buried with her favorite pacifier.

When her father saw the casket, "at that moment I needed the strength of everyone there. I couldn't stand on my own two feet," he said. "It was such a tiny box."

The casket was open. For a reason.

"Please let me see my baby for as long as I can," Milum said.

She wanted to get away from everyone who said Avah was in a better place or that her death was part of God's plan. She was so sick of all that.

Losing a baby "is like standing in quicksand, and everyone is running past you," she said.

"People," Forrester said, "are uncomfortable with your pain."

A few weeks after the baby's death, after the autopsy, detective Pace met again with Avah's parents.

According to Milum and Forrester, Pace told them Avah showed no signs of choking, suffocation or trauma. The only explanation was SIDS; that the baby simply went to sleep and didn't wake up.

"I told him that's what old people do, not babies," Milum said.

"Eventually," she added, "I accepted it."

Pace -- and Avah's parents -- don't remember talking then about the dangers of sleeping with an infant.

"In our eyes, this was an accident," Pace said of his conversation with the parents.

Co-sleeping "was not the best course of action, but it wasn't criminal," he said.

'Known risk factor'

The last page of the Pulaski County coroner's seven-page report on Avah contains the state medical examiner's official cause: "Sudden Unexplained Infant Death in Association with Co-Sleeping."

Arkansas, like many states, no longer calls most infant sleep deaths SIDS or considers them natural occurrences.

Following national recommendations, the state medical examiner's office now identifies most as Sudden Unexplained Infant Death, or SUID.

The office lists manner of death as "undetermined" instead of "natural."

Arkansas' Chief Medical Examiner Charles Kokes doesn't discuss specific cases. Speaking generally, he said the "undetermined" manner is "meant to reflect the uncertainties" of how and why the baby died.

In a few infant sleep deaths, parents will tell investigators they rolled over in bed and woke up with their baby underneath them.

Kokes' office likely would classify those as "asphyxia due to overlaying." The manner would be "accident," he said.

But in sudden, unexplained infant deaths, pathologists don't find clear evidence of suffocation or any other killer.

"We don't find a disease process or problem that could account for death," Kokes said.

Pathologists do know that most cases "involve infants co-sleeping with other individuals, usually adults, or sleeping in what would be considered an unsafe sleep environment," Kokes said.

So his office's SUID determination sometimes adds "associated with co-sleeping" or "unsafe environment," he said.

"When we classify a death as 'SUID with co-sleeping,' we're not saying the baby died because it was co-sleeping," Kokes said.

"We're simply pointing out that a known risk factor was in place."

'I wouldn't dare'

After Avah's death, Milum and Forrester joined a group of Bereaved Parents of the USA. A chapter meets every third Monday of the month at First Church of the Nazarene on Mississippi Street in Little Rock.

"That has been super helpful," he said.

A blessing, Avah's mother said.

Others in the group know, both said.

The couple has kept several of the baby's belongings, including a blue denim Minnie Mouse dress that Avah wore the weekend before she died. It's in a plastic bag to hold in her scent.

"You want to smell it," Milum said. "But it hurts to smell it."

In mid-February, about six weeks after Avah's death, Milum was at UAMS for a three-month birth control shot that involved a routine pregnancy test. Then came a second test. And a third.

The test results were positive; the pregnancy was unexpected.

Later, "When I was told it was a boy, I was let down and relieved at the same time. I thought, this isn't Avah again."

Kayden Forrester was born last fall on Oct. 5. His mother worried constantly. Until recently, he slept "more often than not" in bed with his parents, as close to Milum as possible.

Otherwise, his mother said, she couldn't sleep for fears about his safety.

In mid-December, she attended a child safety seminar at Arkansas Children's Hospital, which reinforced the elements of safe sleep.

Now Kayden sleeps in his crib, on his back, no toys or blankets, Milum said.

That's what Pulaski County Coroner Gerone Hobbs likes to hear after five years in his job and dozens of infant sleep death cases.

"Because I've seen so much, I wouldn't dare sleep with a child now in my bed," Hobbs said. "That's what I tell my family."

MONDAY: Criminal prosecutions of parents whose children die in unsafe sleep situations are rare in Arkansas, but a Siloam Springs couple was sent to prison for it in 2016.

SundayMonday on 01/29/2017