CAIRO -- Sudanese doctors and aid workers urged the government to declare a state of emergency over a cholera outbreak and delay the start of the school year, which began on Sunday, although authorities say the situation is under control.

The disease, which is passed through contaminated water, has surfaced across the country, including in the capital, Khartoum, prompting the U.S. Embassy last month to issue a warning and note that fatalities had been confirmed. Egypt has begun screening passengers from Sudan at Cairo's international airport.

Some 22,000 cases of acute watery diarrhea have led to at least 700 fatalities since May 20, said Hossam al-Amin al-Badawi, of the independent Central Committee of Sudanese Doctors. He added that the condition is most likely cholera, but the government refuses to officially release test results for it.

Sudanese doctors say the cholera, a bacterial infection linked to contaminated food or water, is progressing. They are urging the government to seek international aid, a step linked to declaring a state of emergency. If left untreated, it can cause death from dehydration.

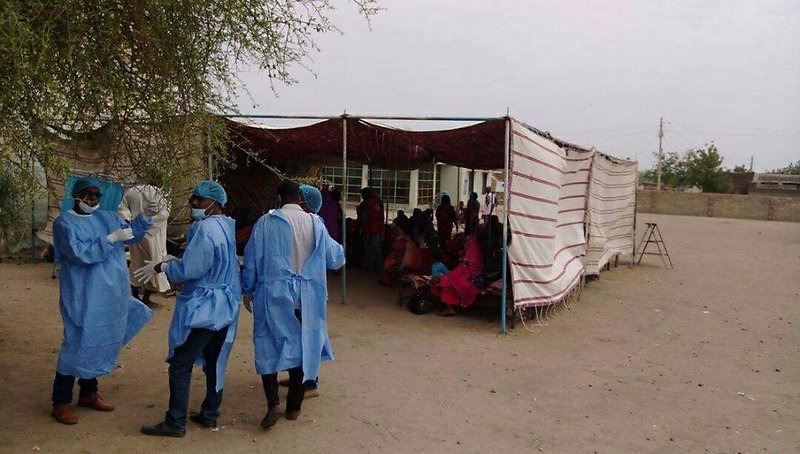

"It risks becoming an epidemic, especially in rural areas," said Alfatih Masoud, of the non-official Sudanese Doctors Union. "Our ministry insists on referring to it as diarrhea for political reasons, and opening schools today is dangerous because they are possible places of rapid transmission." Photos of affected areas online show patients crowded into makeshift tents for treatment.

Masoud said that watery diarrhea is a symptom, not a diagnosis, and that the level of immediacy required for rehydration of patients in the current cases pointed to cholera as the diagnosis.

The official Sudan News Agency meanwhile announced the opening of the school year, saying that authorities had the outbreak of "acute watery diarrhea" under control. Authorities, who have previously acknowledged some 350 deaths, say infections are decreasing.

"Health Minister Bahr Idriss Abu Garda announced a significant decline in cases of watery diarrhea in all states of Sudan, especially White Nile State thanks to the interventions carried out by his ministry," the Health Ministry said in its most recent statement on its website, dated June 13.

Activists and the opposition say President Omar al-Bashir's government refuses to acknowledge the cholera outbreak because it would reveal failures in the country's crumbling health system, where corruption is rife.

"The government silence and inability to confront the epidemic, preferring to achieve political victories, is at the expense of the health and life of citizens," the opposition Sudanese Congress Party said in a statement to The Associated Press. The group is urging all political parties and civil society groups to press for the state of emergency so that Sudan can invite foreign assistance.

Neighboring South Sudan is grappling with the "the longest, most widespread and most deadly cholera outbreak" since it won independence from Sudan in 2011, according to the United Nations. Since the outbreak began a year ago, over 11,000 cases have been reported, including at least 190 deaths, according to the World Health Organization and South Sudan's government.

The arrival of refugees from there poses a contagion risk, the WHO said, because their host areas are overcrowded and lack adequate sanitation.

"The arrival of refugees from cholera-affected areas in South Sudan increases the threat of importation of the disease into Sudan, placing both refugees and host communities at risk," it said in an email.

The group, which has been working in Sudan's affected areas and helping the government vaccinate against cholera, says the response to cholera and acute watery diarrhea is not that different.

"The key point to look at is whether health partners are free to act to provide the care that people need," it said. "At this moment, we are."

A Section on 07/03/2017