Northwest Arkansas is home to more and more people of different skin colors, ethnic backgrounds and languages, the latest census data show.

From the last census in 2010 through July 2016, Benton and Washington counties added nearly 62,000 residents who primarily moved to the region because of job opportunities. They came from different parts of Arkansas, from out of state and from other countries.

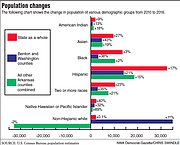

Most of the additional people were non-Hispanic and white, but minority populations are catching up and outpaced the larger group in terms of percentage growth. Hispanic people, whose families originally hail from Spanish-speaking countries and who can be any race, led the way among minorities, increasing by around 14,000.

The numbers reaffirm more than a decade of demographic change in Northwest Arkansas that has helped make this corner of the state its fastest-growing metropolitan area, fueled by an increasingly diverse economy and culture.

"The job opportunities are up there," said Gregory Hamilton, senior research economist for the Institute For Economic Advancement at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. "People are moving up there in search of work."

The change also has heightened the need for multilingual people in health care, law enforcement and other fields and drawn more resources toward bridging newcomers and other residents at work and in school, residents and experts say. The metropolitan area was home to more than 70,000 people who speak languages other than English, or 1 in 7 residents, in 2015, according to census estimates.

Terry Bankston moved here from Cincinnati in 2010 for his former job with Wal-Mart Stores Inc., focusing on managing diversity and recruiting programs for the company and connecting with nonprofit groups around the country.

Bankston plugged into the community by coaching youth basketball with the Boys & Girls Club in Benton County, but he saw a need to help other people feel less like a guest in their new home, he said. In 2016 he became executive director of EngageNWA, which organized a series of forums last year to help newcomers and longtime residents talk and learn more about each other's differences and common interests and concerns.

"Now you know who's sitting next to you in your office," he said, adding more forums are coming in August and September. "We're advocating for people to know a little bit of something about a little bit of everybody."

The numbers

From 2010 to 2016, the state population grew by 2.5 percent to a population of 2.99 million. Benton and Washington county residents made up 16.3 percent of the state's population in 2016, compared with 14.6 percent of the state's population in 2010.

Much of the state's growth occurred in Benton and Washington counties during that time period.

From the 2010 Census through July 2016, the population in Benton and Washington counties has remained about three-quarters non-Hispanic white, though the proportion dropped three percentage points.

Benton and Washington counties stand out from the rest of the state in their Hispanic and black populations. Hispanic residents comprised 16 percent of the population of the two Northwest Arkansas counties, compared to the state's overall population that's just 7 percent Hispanic. It's the second-largest ethnicity in the area.

Conversely, black residents made up 2 percent of the population of Benton and Washington counties, but 15 percent of the state's total population, particularly in the more agrarian southeast.

Charles Robinson, vice chancellor for student affairs and history professor at the University of Arkansas, said the gap goes back to the days of slavery, which wasn't spread evenly throughout Arkansas.

"Slavery existed here, but it was a really small part of the economic reality of this part of the state," he said.

Robinson, who is black, said young African-Americans have often felt the northwest wasn't for them, partly because of the simple fact that there are fewer of them around. Black students' perception of danger or unfriendliness here has faded in the 18 years he's worked here, he said.

"The question then becomes, can I find other people like me," Robinson said. "There's still concern about whether the culture is inclusive enough to where they can find real acceptance and support and opportunity for connecting."

The university is working to attract under-represented groups and make each of them feel welcome and empowered, he added, such as by encouraging them to take student leadership roles or inviting music performers from a variety of genres and backgrounds.

The white population in the two Northwest Arkansas counties is also diverging from the rest of the state by growing instead of shrinking. Arkansas saw a decline of almost 33,000 non-Hispanic white residents from 2010 to 2016. Benton and Washington counties together, on the other hand, added about 35,000.

Washington and Benton counties are home to the bulk of the state's Pacific Islanders, most of them in families from the Marshall Islands. But the community is spreading to other parts of the state, with the share outside of Northwest Arkansas climbing from 14 percent to 18 percent.

Benton and Washington counties, however, gained more residents who are American Indian, Asian, black, and of two or more races.

At work

Amy Riklon, a Marshallese mother of five, decided a year ago to forgo a full-time clerical job at an Arkansas Department of Health clinic to take on a bigger role in health care. She's now studying at Northwest Arkansas Community College to become a registered nurse.

Juggling work, studies and family is a challenge, she told Marshallese high school students last month. But she has seen how a language barrier can lead patients to go on without understanding their medical issues or medications or otherwise not having the experience they should.

"I feel like I need to give my voice," she said.

The influx of speakers of other languages has led to a surge in interest in bilingual employees like Riklon in multiple professions.

Schools for nurses and other health professions, for example, report almost all graduates are snapped up by employers, and those who can speak Spanish or Marshallese are in even higher demand. Dr. Sheldon Riklon, who's related to Amy Riklon through marriage, joined the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences a year ago specifically to help treat the area's Marshallese community and encourage others to enter the field.

Qualified bilingual applicants also are important in law enforcement, officials have said. Rogers Police, for example, made an officer a part-time Hispanic community liaison in 2015. A department spokesman didn't return a message requesting comment Friday.

There aren't chambers of commerce for, say, African-American or Hispanic business owners. But city chambers have offered programs for entrepreneurs and business owners in Spanish or geared toward minorities in recent years.

People in minorities owned or had equal stake in almost 6,000 firms in Northwest Arkansas in construction, food, retail and other industries, according to the latest census Survey of Business Owners in 2012. The number was up almost 2,000 from the survey five years before.

Programs teaching English and other cultural skills for newcomers have also sprung up.

Many of the Tyson Foods plants in Northwest Arkansas employ team members who are predominantly Hispanic and Marshallese, said Kevin Scherer, a company chaplain who is now the company's senior manager for employer social responsibility. He helped create the company's Upward Academy to help bring more stability to their lives and make them more successful employees, he said.

Upward Academy provides English, GED and citizenship classes. The company has worked with the state to provide driver's license tests and test preparation in Marshallese as well.

Irma Gonzalez, a grandmother who works at a Springdale Tyson plant, dropped out of school in Mexico as a young child after her parents died, she said in an interview earlier this year. She spent most of her life unable to read Spanish, much less English.

She can now make doctor appointments, greet co-workers and understand more discussions in English after a year in the academy, which she said makes work and daily life around town much less stressful.

Several plants are piloting a new digital literacy course, Scherer said. The program started because of the needs in Northwest Arkansas, but it will be implemented in all of the company's plants in Arkansas by the end of the year and in plants in other states in 2018.

Northwest Technical Institute's Adult Education Center provides Upward Academy instructors for two of Tyson Foods' plants in Springdale, said Kathleen Dorn, director of the center and vice president of instruction for diploma programs. The academy will give workers in those plants opportunities to apply for higher-paying jobs, she said.

Some of the Hispanic and Marshallese students taking classes through the center have advanced degrees from their home countries but don't know how to transfer their license or how to enroll in college, Dorn said. In other cases, students lack skills in math, reading and writing in their own language.

"You have to start from the very beginning," she said. "We show them how to write a resume, how to dress, what to be prepared for."

In school

Schools have adapted to and have been changed by a more diverse population in much the same ways as the business world.

Roughly half of students in Rogers' and Springdale's districts are Hispanic, and both districts offer outreach programs to help parents learn about and get involved in their children's education.

Rogers offers a Walton Family Foundation-supported retention bonus for Hispanic teachers who stay at least five years. Roger Hill, assistant superintendent for human resources, said the program has helped hire about three dozen teachers, including four for the coming year.

Brig Caldwell, who works as a community liaison at Heritage High School, said last year Hispanic families and the district are gradually communicating more and more, though there's always room for improvement. Caldwell is a citizen who was adopted as a child from Costa Rica.

"We're continually struggling with trying to make sure that our staff, our faculty is in tune culturally with what some of our immigrant families experience," he said.

The NTI center provides instructors for the Family Literacy Program that helps parents learn English in 14 Springdale schools, Dorn said. The parents also spend time learning alongside their children in their classrooms.

The center serves more than 2,100 Springdale students, Dorn said, and that number is expected to grow to 2,300 this year. About 80 percent are adults who do not speak English.

Students in Springdale School District speak 46 languages other than English, and the district had more than 10,000 students receiving services for learning English at the beginning of last school year. In February, 941 English learners graduated from the programs.

"That's a very diverse population," Springdale Superintendent Jim Rollins said.

Teachers, principals, community members and parents work together to meet the individual needs of students, Rollins said. Some of the district's top students are immigrant children, he said.

"When they find themselves in a school setting, they begin to understand the great potential and promise they have, they really do well," Rollins said. "Some are further along than others ... . We know we've got to continue to work very hard."

Northwest Technical Institute also has outreach programs targeting minority high school students and anyone unfamiliar with English or the education system, said Shay Lastra, the programs' coordinator. Lastra meets with students and their parents in an office at the institute, but she also goes to area high schools to provide information about financial aid, the institute's programs and programs at other colleges.

"It's a joy for me," she said. "This is where I get my energy. I feed off the kids."

Lastra said the area still needs interpreters, and she encouraged local officials to consider offering services to help minorities navigate community resources.

NW News on 07/09/2017