America was the Arsenal of Democracy for the Allied nations battling the Axis powers in World War II. That story -- of eventual victory fueled by U.S. industrial muscle -- is well known. So are the famous battles that led to triumph, from Midway to D-Day and a cavalcade of others.

Much less familiar is the role of American generosity in providing succor to the millions upon millions of ordinary Europeans and Asians brutalized by the aggression of Germany, Japan and Italy.

“Work, Fight, Give: American Relief Posters of WWII”

Through Oct. 5, MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History, 503 E. Ninth St., Little Rock

Hours: 9 a.m.-4 p.m. Monday-Saturday, 1-4 p.m. Sunday

Admission: free; donations welcome. The exhibit is a program of Exhibits USA, a national division of Mid-America Arts Alliance, along with the Arkansas Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. Helen T. Leigh provided local funding.

Information: arkmilitaryheritage… or (501) 376-4602

That story is brought vividly to light by a touring exhibit, "Work, Fight, Give: American Relief Posters of WWII," which continues through Oct. 5 at Little Rock's MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History.

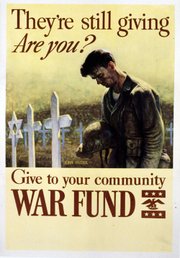

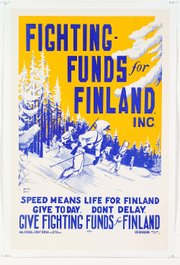

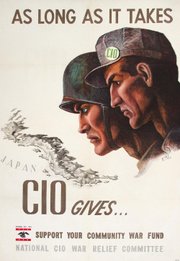

The medium for this message of hope is some 40 posters urging help for more than a dozen nations. They come from

a collection of several hundred posters acquired over the years by Hal Wert, a professor of history at the Kansas City (Mo.) Art Institute.

The poster art was created for an array of agencies, many under the aegis of the National War Fund created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942 to coordinate the welter of relief efforts. The aid continued until 1947, two years after the war's end. It included food, medicine, clothing, ambulances and cash.

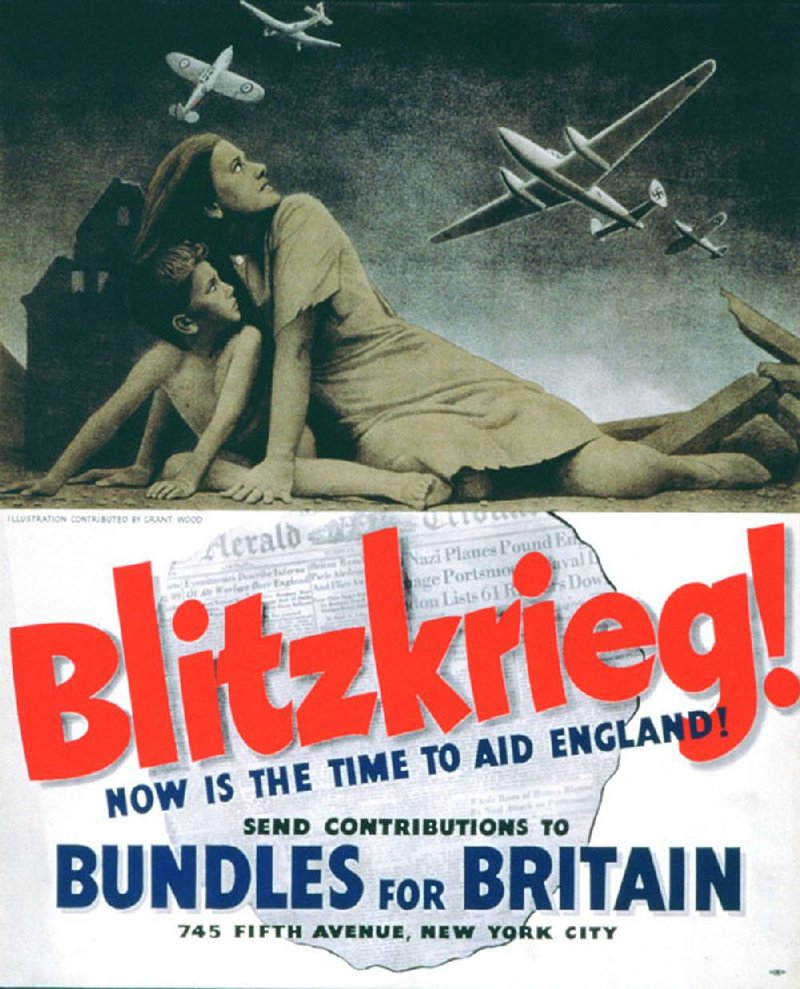

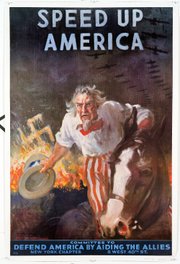

The posters are propaganda in the sense that they seek to stir emotions that will mobilize minds and bring action -- contributions to help war survivors overseas. They were drawn by a host of artists and illustrators including such prominent figures as Grant Wood, James Montgomery Flagg and Martha Sawyers.

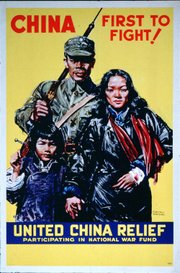

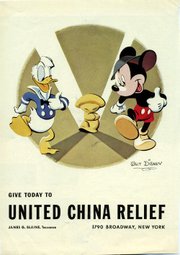

Sawyers created one of the exhibit's most famous posters, for United China Relief. Headlined "China: First to Fight," it portrays an idealized Chinese family in the vast Far Eastern land partly occupied by the Japanese. The father, in military uniform, carries a rifle over his shoulder. The mother, one arm in a sling, holds the hand of their daughter. All three have a look both somber and determined.

Other posters in the second-floor display convey a similarly martial message. A guerrilla fighter about to throw a hand grenade is pictured with the headline "The Fighting Filipinos: We Will Always Fight for Freedom."

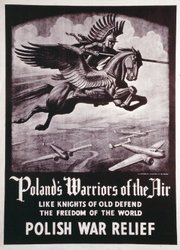

Polish War Relief's message, below the image of a warrior wielding a lance and riding a winged horse, is "Poland's Warriors of the Air Like Knights of Old Defend the Freedom of the World."

A contrasting theme seeks sympathy for the war's hapless victims. Greek War Relief's poster shows the anguished face of a woman along with the message "From Want of Food -- Never From Want of Courage: Greece Needs Your Help Now."

A poster for the Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies pictures two hungry-looking youngsters, one of whom appears to be licking the last bit of food from a bowl. Its headline: "Save a Child in France."

"Blitzkrieg!" is the main headline in a poster that depicts an English mother and child cringing as German bombers pass overhead. The rest of the exhortation: "Now Is the Time to Aid England. Send Contributions to Bundles for Britain."

Wert spoke at the show's opening. He calls his creation "the first exhibition to challenge our traditional memory of World War II, putting relief efforts at the forefront through an array of visually exciting poster art," along with poster stamps (called "Cinderellas"), photographs and banners.

Except for Great Britain, the nations being helped were entirely or mostly under Axis occupation. Their citizens usually received significant assistance only after liberation. This ran counter to the earlier wishes of former U.S. President Herbert Hoover, a major figure in the aid efforts.

Hoover, according to Wert, "advocated feeding the hungry even while their European countries were occupied. He challenged the British blockade of continental Europe, and while he finally lost that argument in 1940, his relief committees did feed people under Nazi rule in Poland, as well as Polish refugees in Romania and Hungary."

Other complications bedeviled aid efforts after the Axis had surrendered in 1945, as Wert points out:

"The relief agencies mirrored the political struggles that occurred in many of the formerly occupied countries for post-war supremacy. This was particularly true of places like Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia as the new communist regimes or factions attempted to torpedo National War Fund aid. Help to Russia was substantial but tricky, as many Americans were skeptical of our uneasy alliance with the Red Bear."

The posters, in Wert's mind, "tell the story of those motivated to do something about the carnage and chaos left behind when the din of battle subsided and the armies moved on. Relief organizations in big cities and small towns alike found creative ways to mobilize Americans and collectively raise many millions of dollars to help those in war zones."

"Work, Fight, Give" complements another MacArthur Museum exhibit, "First Call: American Posters of World War I," displayed in a first-floor gallery during centennial commemorations of the U.S. entry into what was then known as the Great War.

These posters were collected by Little Rock native Thomas Wilson Clapham. After his death in 1992, the posters were nearly discarded before they were donated to the museum in 1999 and were later conserved through donations by Helen T. Leigh of Little Rock.

Stephan McAteer, the museum's executive director, sees a clear connection between the two exhibits:

"They show how powerful posters were in influencing public opinion and in funding the conduct of the wars and the recovery from them. Propaganda posters helped raise two-thirds of the total U.S. cost of World War I. The relief posters of World War II raised around $321 million to aid war-ravaged countries. That would amount to about $4.4 billion today."

As for what visitors can take away from viewing the relief posters, McAteer sees them as "a powerful reminder of the continuing need for philanthropy in our tumultuous world, and how the Greatest Generation met that challenge. The poster artists used historical, mythological and cultural symbols to connect with Americans whose roots lay in other nations, reflecting how diverse our country is -- and remains today."

Style on 07/16/2017