A man in a white pickup pulled up to CHI St. Vincent Infirmary in Little Rock the morning of April 11, pushed two limp bodies out of the vehicle and drove away.

Nurses went outside and found Madeline Tate and a 22-year-old friend lying on the ground. The two were blue in the face and struggling to breathe. They were dying.

Nurses found a syringe and a spoon in the friend's pocket and determined that he and Tate had overdosed. They quickly moved Tate, 20, and her friend to the emergency room and injected them with naloxone, an anti-opioid medicine used to reverse the effects of an overdose.

The normally fast-acting antidote took effect slowly. But their heart rates stabilized and their breathing returned to normal.

Their lives had been saved.

Tate and her friend later told doctors that they had injected themselves with two drugs. The first was heroin.

The second was fentanyl, a synthetic painkiller that is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine.

RELATED STORY

The overdoses, as detailed in a police report and recalled by Tate and her family, were among a rising number across the country involving fentanyl and its powerful analogs.

Law enforcement encounters with fentanyl spiked from roughly 1,000 in 2013 to 14,400 in 2015, according to the latest report from the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, a program of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration that collects information from forensic labs.

Fentanyl is often prescribed as a patch or spray to treat chronic pain, but black-market versions of the drug, manufactured in China and Mexico, are being used to replace or amplify heroin, according to a DEA report.

"Due to the high potency of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, transnational criminal organizations across the globe are competing for the U.S. market," the report says.

That market is easily accessible. Fentanyl can be purchased online, in a variety of forms that include powders, pills and liquids, from sellers overseas.

It's acquired through theft, as well. In Little Rock, police have fielded numerous reports of prescription fentanyl vanishing from nursing homes, pharmacies and medicine cabinets.

Fentanyl is not the scourge in Arkansas that it is in other states -- Kentucky authorities connected it to nearly half the overdose deaths in the state last year -- but the potent synthetic painkiller is showing up more frequently in the Natural State.

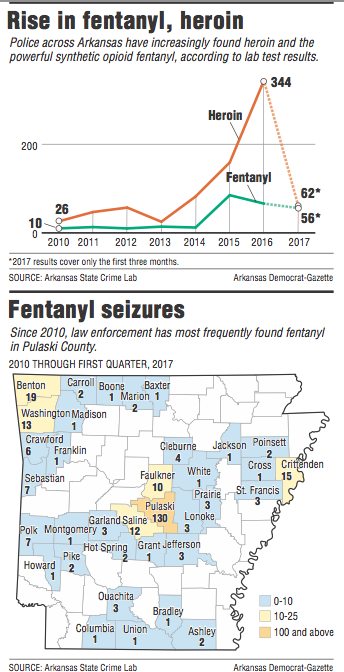

The Arkansas Crime Laboratory identified 56 positive samples of fentanyl through the first three months of 2017, commonly as an off-white powder or as a compound in counterfeit pills, said Felisia Lackey, the lab's chief forensic chemist. That compares with 66 positive samples in 2016, 85 the previous year and 12 in 2014.

The relatively small number of fentanyl cases in Arkansas has still been enough to gain the attention of hospitals, ambulance services and law enforcement agencies.

Metropolitan Emergency Medical Services of Little Rock, the largest ambulance service in the state, and UAMS Medical Center, the largest hospital system in the state, met in June to discuss developing intergency guidelines on treating fentanyl overdoses.

MEMS Executive Director Jon Swanson said there are concerns over whether naloxone, the anti-opioid medicine, is strong enough to revive someone who has overdosed on fentanyl or carfentanil, the drug's more powerful cousin.

Swanson said there are also concerns for medics and other first responders. Toxicologists say exposure to the smallest amounts of fentanyl through inhalation can be deadly. In larger amounts, skin contact can be deadly.

"One of the concerns that we would have is recognizing the presence of the stuff," Swanson said. "It might not be apparent to us."

UAMS spokesman Leslie Y̶o̶u̶n̶g̶ Taylor* said the hospital has not seen a notable increase in fentanyl-related cases but is working to address safety concerns associated with the drug.

The hospital has posted fliers to warn staff members about carfentanil and the "significant threat of overdose for anyone coming in contact with this drug." The fliers, which show a lump of powdered carfentanil, urge staff members to immediately contact a supervisor, police or the Occupational Health and Safety Administration if they encounter the drug.

"We're taking a proactive approach in light of news around the country," Y̶o̶u̶n̶g̶ Taylor* said.

Little Rock police are also examining how to handle fentanyl encounters.

Records show that department commanders have circulated DEA training videos on how officers can protect themselves from exposure to the drug. Police spokesman Lt. Steve McClanahan said the department is looking into equipping officers with naloxone, as well.

Benton police and the Pulaski County sheriff's office are among the law enforcement agencies in central Arkansas that already carry the overdose antidote.

Arkansas Drug Director Kirk Lane, the former Benton police chief, said fentanyl is perhaps the strongest and cheapest option in a "circle of addiction" for many of its users.

He said that circle often begins with prescription pain pills, which Arkansas, like many states, has in abundance. In 2012, doctors in the state wrote 116 painkiller prescriptions for every 100 people, according to the IMS Health National Prescription Audit. That ranked as the eighth-highest rate in the nation.

In 2015, doctors prescribed enough hydrocodone to supply every Arkansan with 37 pills for the year, according to an Arkansas Prescription Monitoring Program report.

Lane said that when some people build a tolerance to prescription painkillers, it becomes cheaper to use heroin, which police across central Arkansas have found more regularly, and in larger quantities, in recent years. State Crime Lab data show positive heroin tests have increased from 82 in 2014 to 159 a year later and 344 in 2016.

Lane said the "circle of addiction" then leads to an even stronger, cheaper substance -- fentanyl.

That's how it happened for Madeline Tate. Her parents, Tom and Hope Hankins, said she started abusing prescription pills as a teenager and eventually moved on to harder and cheaper drugs, including meth and heroin.

Tate said that the morning of April 11, the day she was left clinging to life outside CHI St. Vincent Infirmary, she and the 22-year-old friend had been going through heroin withdrawal.

After countless phone calls in search of the drug, they finally found a seller at a house on Colonel Glenn Road in Little Rock. They bought a bag of heroin and a bag of fentanyl, which Tate said she and her friends thought of as "the good stuff."

"I just knew that if you were sick, it would make you feel better," she said.

They combined the heroin with small amounts of fentanyl and shot up with Tate's boyfriend in his pickup. Almost immediately, Tate knew something was wrong. Her boyfriend froze up. She looked at her friend in the backseat and saw he'd also gone stiff.

"And then I started to go out," Tate said. "Looking in the rearview mirror, that's the last thing I remember."

Tate awoke in a hospital bed. Doctors told her she was lucky. They said that if her boyfriend had waited just minutes longer to dump her and the friend outside the hospital, she would have died.

Tate said in a phone interview from a drug rehabilitation center that her fentanyl overdose was a wake-up call.

"We didn't realize how strong it really was," she said.

A Section on 07/17/2017

*CORRECTION: Leslie Taylor is the spokesman for UAMS. A previous version of this story had an incorrect last name.