Methamphetamine remains a problem in Northwest Arkansas despite fewer homemade labs and the spotlight on opioid abuse.

Pure grade meth rolls in from Mexico with central Arkansas a trafficking crossroads, said Tim Jones, resident agent in charge of the Fayetteville office of the Drug Enforcement Agency.

“We’re seizing about 100 pounds per year,” Jones said of the Northwest office. “You figure we’re only getting a small portion. It could be 1,000 pounds a year coming in.”

The Fayetteville office has arrested 1,738 people on meth-related complaints and seized 633 pounds of meth in Northwest Arkansas cities and Fort Smith since 2010, he said.

Mexican meth brings an intense high for not a lot of money. It also comes with old meth-related problems, officials said.

“Drugs fuel so many other crimes,” Jones said. “People are ‘methed out’ to the point that reality doesn’t exist for them. You’re dealing with people who are willing to hurt you to get their next high.”

Benton County Circuit Judge Tom Smith, who presides over adult drug court, juvenile drug court and veterans treatment court, said addiction feeds into other crimes such as theft, including breaking into homes, and violence.

“I’ve had cases where people have been on a controlled substance, and they can’t tell why they did what they did because they’re so out of their minds,” Smith said.

Methamphetamine also can be fatal.

Carol Davidson, 35, of Siloam Springs died as a result of meth use. Rosemarry Davidson, her 22-monthold daughter, died alongside her. They went missing Nov. 12 and their bodies were found in February near Lookout Tower Road, roughly 12 miles southeast of Siloam Springs.

The Arkansas Crime Laboratory determined Carol Davidson died accidentally because of methamphetamine intoxication with contributing environmental hypothermia. The child’s death was left undetermined, but most likely due to starvation or environmental hypothermia, Sgt. Shannon Jenkins with the Benton County Sheriff’s Office said in April.

MEXICAN-MADE

Meth enters the U.S. through the southern border states and is taken across the country on major highways and interstates. Interstates 40 and 30 are the two major trafficking corridors in Arkansas. Shipments through Little Rock have resulted in law enforcement making 100-pound seizures. Shipments in and through Northwest Arkansas tend to range from 10 to 20 pounds, Jones said.

“It has slowly changed from homemade methamphetamine to Mexican methamphetamine,” said Lt. Jeff Taylor, public information officer for the Springdale Police Department. “This is due to the purity being higher and items to manufacture homemade methamphetamine are harder to come by.”

Jones has worked in the Fayetteville DEA office for four to five months, but he’s been with the DEA for 20 years. He was an agent in Florida in 2004.

Mexican meth has become the preferred meth everywhere, pushing out local labs, Jones said.

Mexicans who smuggled cocaine into the U.S. for Colombian cartels decided to go into business for themselves and manufacture meth, Jones said.

The gang MS-13 is involved with importing meth, serving as smugglers, said Jones, who credits state and local law enforcement agencies with preventing gangs from establishing a foothold in Northwest Arkansas.

Mexican meth manufacturers make a product 90 percent to 95 percent pure in large laboratories, whereas homemade labs have a 50 percent or lower purity level, Jones said.

“In the early 2000s, there would be guys who couldn’t sell their product because the purity was so low,” Jones said. “The super labs [in Mexico] refined the process.”

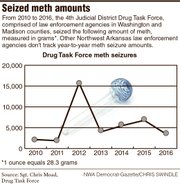

Jones said his office saw a sudden rise in methamphetamine seizures between 2010 and 2012, going from seizing 10 to 15 pounds of meth a year to 95 to 110 pounds.

“That’s when the super labs started taking hold,” he said. “People south of our borders saw an opportunity and jumped all over it.”

Meth is moved from Mexico to the U.S. as any supply chain, said Sgt. Chris Moad with the 4th Judicial District Drug Task Force based in Fayetteville.

“Large quantities are typically smuggled across the border and then dispersed to organizational contacts,” Moad said. “Those contacts disperse smaller quantities to area dealers, who then further disperse it. This may start in the hundreds of pounds and be dispersed all the way to a small local dealer who sells grams.”

Meth is brought into the U.S. in crystal form or as a liquid taken to a conversion lab and crystalized, Taylor said.

Mexican meth also is cheaper to buy compared to anything made locally. One pound of Mexican meth has a street value of $8,000 to $10,000. It sells for $500 to $700 an ounce.

“That’s mainly because of the mass quantities that they’re making in these super labs. It drives the price down,” Jones said. “When you make 40 pounds in a cook instead of 4 ounces, then you have a larger quantity to sell and you can lower your prices.”

Detrimental effects on the use are the same despite the purity, Jones said.

“It’s very corrosive to the body,” he said.

LOCAL LABS

Meth isn’t as easy to manufacture locally as it used to be. The stimulant had its heyday in the early 2000s, but federal and state lawmakers made moves in the mid-2000s to curtail meth manufacturing.

Congress passed the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act in 2005 requiring pharmacies and stores selling medicine to keep purchase logs of all products containing pseudophedrine, an ingredient used to make meth, and limit the amount of products a person could purchase over time. Pseudophedrine is decongestant used in cold, allergy and sinus medicines.

Arkansas started its fight the same year when the General Assembly passed Act 256, which required pharmacies to sell certain cold medications from behind the counter. Act 508 was passed in 2007 to create a law enforcement database to track pseudophedrine amounts sold in each pharmacy. Act 588, passed in 2011, requires pharmacists to make a “professional determination” on whether someone without a medical prescription needs pseudophedrine based on symptoms and medical history.

Northwest Arkansas meth manufacturing has become rare because of these restrictions, officials said.

“There’s almost no manufacturing arrests,” Sgt. Jason French of the Fayetteville Police Department said. “We arrest a number of individuals for trafficking, delivery, possession with purpose to deliver and possession.”

There were close to 1 million purchases of pseudophedrine in the state before Act 588 was passed. That number fell to 191,926 a year after the law was enacted, according to the Arkansas Crime Information Center.

The Northwest Arkansas meth labs that remain are crude and minuscule, Taylor said.

“The ones that are located are one-pot and old-fashioned anhydrous ammonia labs,” Taylor said.

Springdale police made 47 meth-related arrests in 2011. Only two of those were in connection with manufacturing. Springdale has only made two other meth manufacturing arrests since then, both in 2013, according to numbers provided by Taylor.

LAW ENFORCEMENT

Northwest Arkansas law enforcement agencies, including police departments in Fayetteville, Springdale, Rogers and Bentonville as well as sheriffs’ offices in Benton and Washington counties, describe methamphetamine as either the most abused narcotic in their area or at the top alongside opioids, which are prescription-strength painkillers.

“Meth is by far the most abused narcotic in Benton County,” Jenkins said.

Springdale police have detectives assigned to the DEA’s task force and the 4th Judicial District as well as its own narcotics division, Taylor said.

Undercover operations are essential to bust meth distribution, and turning those arrested for meth possession and distribution into informants is the DEA’s “bread and butter,” Jones said.

“Everybody talks. Even those who swear they won’t, they will eventually,” he said.

Cartels have found it more difficult to get meth into the U.S. in recent months, Jones said.

Tighter border security and greater scrutiny on gangs and drug trafficking organizations has caused a “slight decline” in distributing and selling meth, he said.

LOOKING AHEAD

Decision Point, 602 N. Walton Blvd. in Bentonville, treats substance addictions. Many of its clients are referred to them by the court system.

Decision Point treated 813 people in fiscal 2016. About 40 percent, or 324, reported meth as their primary drug of choice; 249 people, or 30 percent, reported alcohol as their primary addiction; and 153, or about 19 percent, reported opioids.

Decision Point only treats adults, said Raymon Carson, its regional director.

“But there are kids who abuse meth,” Carson said. “I’ve had clients talk to me about their age at first use. The youngest persons I’ve heard about using methamphetamine are 9 and 10 years old.”

A woman who received treatment at Decision Point, and who asked not to be named, said she started using drugs 22 years ago. She said 14 years ago she tried meth for the first time. The drug gave her a euphoric feeling, she said, and she quickly became addicted. She began making the drug and eventually was taking more than she was making.

She lost her job and ended up in prison, she said. She started using meth about a year after her release from prison and was arrested again. That’s when she checked herself into Decision Point. Sober now, she credits treatment, Narcotics Anonymous and her resolve to give up drugs.

While meth is the top narcotic in Northwest Arkansas, Jones doesn’t underestimate the rise of opioids.

“The guys selling meth are still trying to get into the pills and the opioids,” he said. “It’s all driven by cash and greed.”

Jones said it’s hard to tell whether meth will increase or decline in Northwest Arkansas, but he’s optimistic.

“I believe with education, things will get better,” he said. “The efforts at the border are making it harder to get the stuff in here, and we are doing what we do to get the drug predators and stop what they’re doing, which is just in time for us to focus on the opioid epidemic.”

Hicham Raache can be reached by email at hraache@nwadg.com or Twitter @NWAHicham.