CHICAGO — Research on 202 former football players found evidence of a brain disease linked to repeated head blows in nearly all of them, from athletes in the National Football League, college and even high school.

It's the largest update on chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a debilitating brain disease that can cause a range of symptoms including memory loss.

The report doesn't confirm that the condition is common in all football players; it reflects high occurrence in samples at a Boston brain bank that studies CTE. Many donors or their families contributed because of the players' repeated concussions and troubling symptoms before they died.

"There are many questions that remain unanswered," said lead author Dr. Ann McKee, a Boston University neuroscientist. "How common is this" in the general population and all football players?

"How many years of football is too many?" and "What is the genetic risk? Some players do not have evidence of this disease despite long playing years," she noted.

It's also uncertain if some players' lifestyle habits — alcohol, drugs, steroids, diet — might somehow contribute, McKee said.

Dr. Munro Cullum, a neuropsychologist at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, emphasized that the report is based on a selective sample of men who were not necessarily representative of all football players. He said problems other than CTE might explain some of their most common symptoms before death — depression, impulsivity and behavior changes. He was not involved in the report.

McKee said research from the brain bank may lead to answers and an understanding of how to detect the disease in life, "while there's still a chance to do something about it." Currently, there's no known treatment.

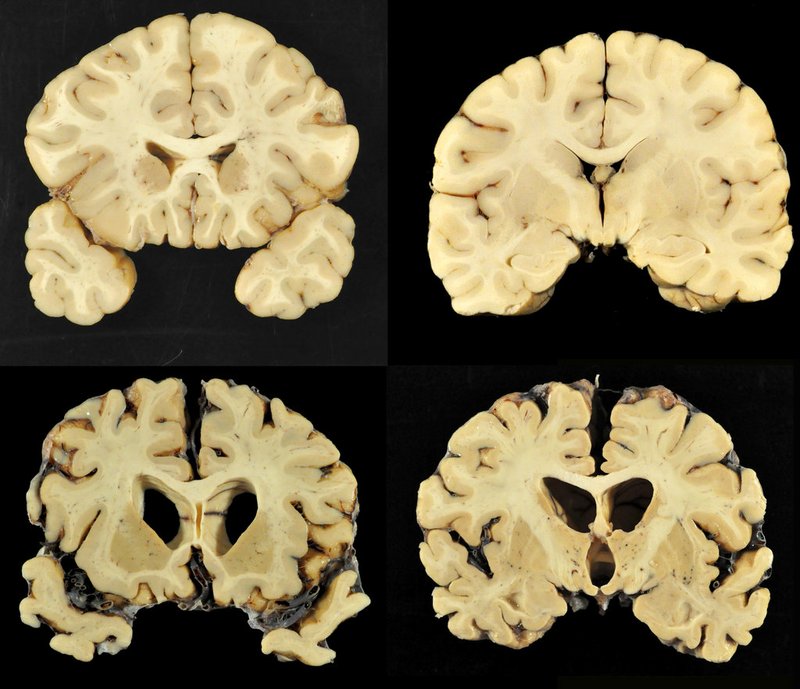

The strongest scientific evidence says CTE can only be diagnosed by examining brains after death, although some researchers are experimenting with tests performed on the living. Many scientists believe that repeated blows to the head increase risks for developing CTE, leading to progressive loss of normal brain matter and an abnormal buildup of a protein called tau. Combat veterans and athletes in rough contact sports like football and boxing are among those thought to be most at risk.

The new report was published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association.