MALVERN -- Two years ago Gov. Asa Hutchinson stood in a boardroom outside his office, pointed to a display board and hailed re-entry centers as a key to the state's overpopulated prisons.

This month, inmates at the state's largest re-entry center stood in front of state officials and their peers and gave testimony to the healing powers the center's programming has had on their lives.

"I ain't never thought I'd have a job for this long of time."

"This is what I needed to become a grown man."

"This is the first time anyone has ever given me a chance."

The idea of re-entry centers isn't new. The private facilities contract with Arkansas Community Correction to take prisoners within 18 months of their release dates for a six-month residency program that reintroduces them to society by way of life skills, addiction treatment and employment. Several states around the nation employ the idea, and other state officials have raised the suggestion for years.

But Hutchinson decided in 2015 to put money behind the endeavor -- $5.5 million from state insurance reserves and unclaimed property funds. Hutchinson earmarked a total of $32 million in two-year costs for his prison plan that also included nearly 800 new prison beds and increases in parole staffing levels.

The plan's main purpose, he said at the time, was to ease the prison population and to reduce the state's high recidivism rate.

It's too early for measurements -- the recidivism rate and population numbers -- to gauge the success of the initiatives, but those numbers seem to be creeping higher.

The recidivism rate, which measures how many inmates return to prison within three years of their release, is up to 51.8 percent from the 43 percent it was two years ago.

On the day Hutchinson unveiled the plan, the prison system was bursting at the seams with 15,341 inmates, 107 percent of prisons' 14,331 capacity. Another 2,631 state inmates were housed in county jails. Today, 17,798 inmates are behind prison bars and another 1,212 are housed in county jail backups, according to the latest reports from the Arkansas Department of Correction.

It will take time and commitment to see a difference in the numbers, but the most important impact is the lives turned around, said J.R. Davis, a spokesman for the governor.

"We're still very much in the early stages of this," Davis said. "I think what we're seeing is what the governor had envisioned -- giving those that go to jail a second chance. People make mistakes, and they are responsible for those mistakes. But let's change behavior; let's give people a chance to change."

In high demand

When Katy Petrus answers the phone in her office as director of Covenant Recovery, the state's largest re-entry center, she shakes her head before uttering a word.

The caller, a local manufacturer, is pleading for eight more employees.

"We're maxed out. We have no one else to send," Petrus said.

The center houses up to 100 inmates. Only those who have passed the 21-day mark are eligible for employment.

The first phase at the center is an adjustment period, a time for prisoners to get prepared for the real world. Petrus helps them get their Social Security cards, driver's licenses and enrolls them in the local college.

Petrus unfurls a list of employers who call and who ask her to send workers.

Initially when Petrus and Jeremy McKenzie, founder of Covenant Recovery -- which includes two re-entry centers in Pine Bluff as well as a Malvern location -- introduced themselves to the community, the reception wasn't exactly warm.

"I asked them to just give us a chance," McKenzie said.

The tide started to turn when McKenzie and Petrus sent the inmates out on volunteer projects like city cleanups and the local Neighborhood Watch programs. Soon, requests were coming in from city officials and community members. The two answered the call from the Malvern Fire Department to clean up the house of a lady who had more than 100 cats.

"The city was going to condemn her," McKenzie said. "We went in there and cleaned everything, inside and out."

Word quickly spread among local employers that the center's residents were going to show up for the job each day, work hard and be drug-free.

"I'm proud of the ones we have," said James Scallion, manager of garden operations at Garvan Gardens in Hot Springs. "Two of them have taken full advantage of the opportunity. They've graduated, are homeowners and got their kids back."

Garvan Gardens has used up to 60 employees from the center each year, with some taking permanent posts after they graduate from the program.

"I wish I had more jobs, more opportunities to help," Scallion said. "We give people a second chance, a chance to be re-acclimated to society and become productive citizens. I'm tickled to death."

Mark Lobel with Dock Leveling Manufacturing said he encourages other employers in the area to give the center's residents a chance.

"They're eager to be here. They work hard," Lobel said. "They appreciate the chance. I know how a lot of people look at felons, but they've paid their dues."

Still, they're not perfect, Lobel said. He said out of every 10 employees he gets from the center, about two don't make it.

On Day 150 of the program -- the last phase of the 180-day program -- the inmates are autonomous. They are acquiring their own housing and making their own decisions with only a weekly drug test and ankle monitor to hold them accountable.

It's during this time that they are more likely to fail, said Carrie Williams, the assistant director over the Arkansas Community Correction's re-entry program.

"We have some of them at Day 150 saying, 'I can't do it.' 'I'm not ready.' 'I'm scared.' They're used to somebody telling them what to do," Williams said. "They go to work, but then when they're home there's no one there. The next thing you know, someone calls and there you have it."

Several of the inmates stay at the center past the six-month mark, even though completing the program makes them eligible for early parole. If the center staff determines that the inmate is not ready to be released into society, it has the option of keeping them until their original parole eligibility dates.

The re-entry centers teach structure and accountability. There are no guards with guns or locked gates. Covenant Recovery is a family setup, with shared chores and individual responsibility. Some inmates just cannot handle that level of freedom, said Dina Tyler, a deputy director of the Community Correction Department.

Of the 669 prisoners sent through a re-entry center program since its inception, about 34 percent, or 229 inmates, didn't make it and were sent back to prison to complete their sentences. A failed drug test or getting fired from a job automatically revokes the inmate's eligibility for the program.

"They come out of prison, and they have to build structure themselves. They don't know how," Tyler said. "If they had known how to build structure in their life with the right planks and support beams in place, they wouldn't have been to prison in the first place.

"That's what we're trying to teach them now."

Trial and error

At a recent group meeting at the facility, a large, heavily tattooed man smiled broadly as he leaned forward in his chair, took his driver's license out of his wallet, and waved it back and forth like a flag in front of about 40 of his housemates.

"It's been years since I had one of these," he boomed.

Another man, who referred to himself as a "seven-time loser" for his seven stints in prison, said his success in the center's program gives him hope for the first time in his life.

"I turned 18 in Tucker prison," he said. "I ain't going back."

Another teary-eyed man testified that he's working a "real job" now, something he never saw for himself.

"You have a real opportunity," he said. "These aren't minimum-wage jobs. These are $15-$20-an-hour jobs. This wouldn't have happened just coming out of prison with $50 and a bus ticket."

The outcomes, as illustrated in the testimonial group meeting, were the best that the state had hoped for, said Williams, the state leader of re-entry.

But their fears, to a degree, also have been realized.

Inmates at some facilities walked off, and drug use is an ever-present issue.

The selection process for an inmate's participation is strenuous. An inmate must apply, show a willingness to work in the program and have a clean prison discipline record. And only moderate- to high-risk inmates are eligible.

"If they're low risk, you do nothing for them. Chances are they're going to make it," Tyler said. "You want to concentrate your resources where they're needed most, and that's those that are most likely to re-offend. Those are your high and medium risks."

The first female to graduate the re-entry program was in prison for first-degree murder. She's now working at a prison transitional house as an employment specialist.

"She's done very well," Williams said. "She'll tell you this is something she didn't ever expect to happen to her."

The inmates sent to re-entry are already on their way out of prison and into the communities, Tyler said. With the re-entry program, their issues can be addressed to send them in a new direction, she added.

The re-entry centers have been the most surprising aspect of the process, Tyler said.

"It's a long, drawn-out process to get approved as a re-entry center," she said. "We thought at first it would take a month, six weeks tops. But first someone has to decide they're going to open a center, then they scout for a building. They have to go through our approval process and then the city licensing procedures."

And once the centers are up and running, the state monitoring system is stringent. They are subjected to random and annual inspections. Their performance is graded based on measurements like the number of graduates, how many drug tests return as positives, the adequacy of the facility and the feedback from inmates.

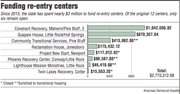

Of the 12 original re-entry centers, only six remain. Some changed to transitional housing -- which takes inmates who have already made parole -- while others were closed by the state.

Still, the future is re-entry, Tyler said. In the past two years, the state has paid out $2.7 million to re-entry centers for their service. The cost could be much higher, but the centers charge $14 per day in rent to the inmates once they are employed. Also, the daily rates paid by the state to re-entry centers -- $20 for moderate risk, $26 for high risk and $30 for sex offenders -- is much lower than the $60 average per day per inmate that state prison officials estimate it costs to house inmates in Arkansas prisons.

The state needs more: more centers and more funding, Tyler said.

"It's a new program. You're starting from scratch. There's going to be some trial and error," Tyler said. "The important thing is you try to fine-tune things, but you don't quit. The dream is that someday, everybody who leaves prison will go through a re-entry center."

A Section on 07/31/2017