We've been playing a lot of Gregg Allman around the house these past few days.

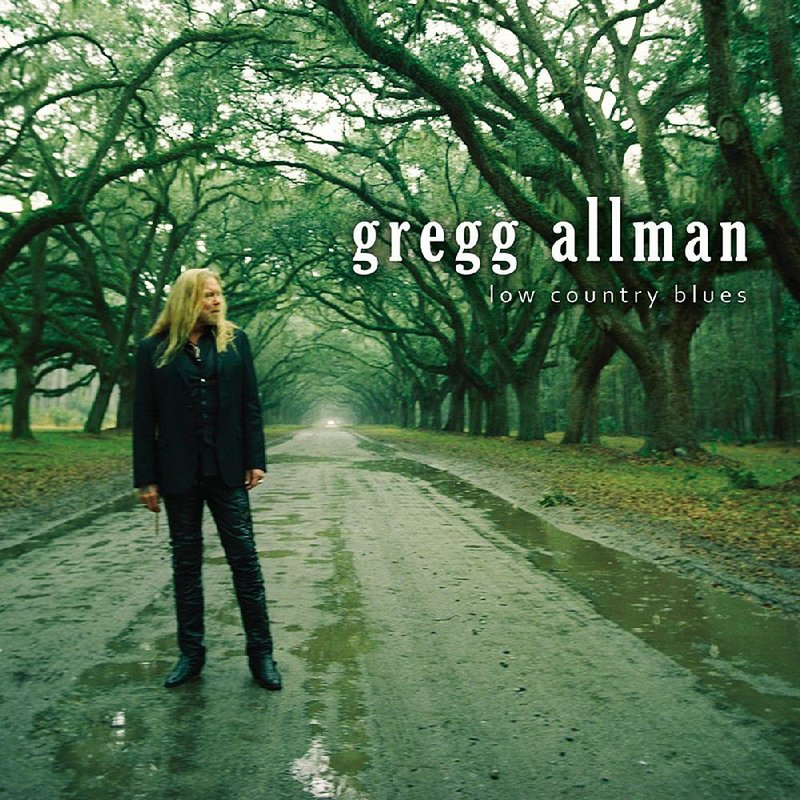

There's this song, the first track on 2011's Low Country Blues, which now looks like it's going to be Allman's last studio album (though it's dangerous to make definitive statements about these things -- Chuck Berry's first since 1979 is about to come out), called "Floating Bridge." Written by Sleepy John Estes, who recorded it in 1937, it's a deceptively simple blues song about a man who nearly drowns when he is somehow trapped under the titular span.

It's based on the true story of how Estes almost died when a bridge collapsed near Hickory, Ky. Estes was thrown into the water and trapped under the bridge until his friend and harp player Hammie Nixon dove in and pulled him out. If you listen to Estes' version -- and in the age of YouTube there's no reason not to -- you might come to understand why Sleepy John came to be associated with "crying the blues." The shuffle tempo is relaxed, but the plaintive urgency of the drowning man comes through in Estes' reedy, shaky timbre. It's a song about facing mortality close up and getting a second chance.

It's also a vocal performance that would seem to daunt any would-be cover artist. Eric Clapton recorded it, but Clapton's perfunctory approach to singing has always been part of his charm. Allman was a singer even more than he was a master of the Hammond B-3 organ, and his version of "Floating Bridge" comes close to cutting the original.

Allman's version features a swampy thump of bass, palm-muted acoustic guitar and Dr. John's piano, with Doyle Bramhall II's electric guitar occasionally flashing in the background. While the production -- by the estimable T Bone Burnett -- is hardly minimalist, it's all pushed back behind Allman's growling, serrated, yet marvelously restrained voice:

They carried me out the water, they laid me on the bank

About a gallon of muddy water I had drank

When he was recording the album, Allman was waiting for a liver transplant, and there was an unspoken assumption that Low Country Blues could be a posthumous release. It wasn't, and his surprisingly thin solo discography was augmented by the release of the live double CD and DVD Back to Macon, Ga. in 2015.

Low Country Blues was Allman's first album in 14 years (he had two nine-year droughts in his career). Maybe if you're familiar with his career it's not hard to figure out why. Some years he was busy with the Allman Brothers, some years he was busy doing drugs or hanging out with Cher. Most people who pay attention to such things would probably say his solo career was a footnote to his work with the Allmans -- although if you pick up the 1997 anthology One More Try, a two-disc (34-track) collection that covers his career from 1968 to 1988 and includes a couple of Allman Brothers cuts, you might be surprised to discover exactly how versatile and nuanced a vocalist he could be. You can pick up Ray Charles and Hank Williams in his voice.

I wasn't planning to write about Allman, who died May 27, in part because I hate the way newspapers tend to run reflexive appreciation pieces after pop figures die. Too often it's a case of firing up Wikipedia and pulling out the Rolling Stone Random Guide to the Biggest Rock Star Encyclopedia to describe the staggering progress of the inevitably down-pulled career. Maybe you'd say something about how Gregg taught his older brother, Duane, to play guitar, and how in their first band Gregg was the lead guitarist while Duane sang and played rhythm. But Duane wasn't much of a singer, and Gregg, well, he couldn't play guitar like Duane, so they swapped roles.

Maybe you'd write something about their father, an Army officer who was murdered by a hitchhiker on the day after Christmas in 1949. Maybe you'd talk about the brothers' stint in Castle Heights Military Academy in Lebanon, Tenn., where they were sent when their single mother refused to put them in an orphanage.

You'd blow through the early bands, the Allman Joys, Hour Glass and the 31st of February, their early years in Los Angeles (where, for a time, Gregg roomed with Jackson Browne) and maybe touch on Duane's session work at Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Ala., and how all he really wanted was to get his baby brother to come back from California and be in a band with him.

Then you'd relate the long, strange trip of the Allman Brothers, the tragedies and the fallings out, and the great records followed by the inevitable slide. You'd note how they will forever be identified with something called Southern rock even though they were really closer to Coltrane than Molly Hatchet.

The Allman Brothers were never loud and obnoxious boogie artists. They were subtle, intelligent musicians who -- along with the Grateful Dead and Cream -- pioneered the progressive, improvisational possibilities of rock. Their early work combines the earthy imperatives of Delta blues with the ethereal sky-crying of John Coltrane. They could stretch out and jam, but their jams only occasionally came across as self-indulgent or meandering.

In one form or another, they persisted for 45 years -- almost twice as long as Duane Allman lived. Gregg outlived his brother by nearly 46 years. And he never got out of his shadow. Not even when he was married to Cher.

...

I was hoping that Low Country Blues would lead to a late career renaissance for Allman, and it did help a little -- it's his best solo album, even better than 1973's Laid Back, which sounded pretty good in its day and even better now -- but maybe he was too sick to capitalize on it.

Or maybe he just didn't have the material -- 11 of the 12 songs on LCB were covers, and the one original -- "Just Another Rider" was an obvious call-back to "Midnight Rider." Though he wrote some amazing songs -- "Whipping Post," "Melissa" -- Allman was never a prolific songwriter. He was never more than a passable lyricist who tended to lean on hoary blues tropes and repeated lines. In the context of the Allman Brothers, which could stretch out instrumentally, his durable melodies could be passed from player to player like a joint. But his solo records were more pop and soul-oriented, and called for a different kind of focus. Allman was better at breathing life into old blues than trying to write a pop hit.

It's telling that his biggest solo hit, 1987's "I'm No Angel," was written by a couple of British dudes, session guitarist (and Ray Davies' nephew) Phil Palmer and country rock pioneer Tony Colton (front man for the forgotten outfits Head, Hands and Feet and The Poet and One Man Band). Allman wasn't even the first to record the song. Former Righteous Brother Bill Medley originally recorded it for his 1982 album Right Here And Now. (Cher, to whom Allman was famously married from 1975 to 1979, used to do the song on tour.)

...

I had a conversation with Allman once.

It wasn't an interview, just an interaction. We were backstage at a friend's show. It was at a pretty low point in Allman's career, before the mild comeback that "I'm No Angel" offered (in his autobiography My Cross to Bear he admits he spent much of the '80s in a drug- and alcohol-infused fog). He felt at loose ends and was looking around for a project. He thought he might produce an album for my friend. That never happened, though somewhere I have a cassette full of demos for the proposed project.

I mentioned that my friend was about to audition for the part of Jim Morrison in a movie -- not the Oliver Stone movie. Allman nodded, noting the physical and sonic resemblance. We both thought he made a good enough Morrison, though Allman didn't think he had enough crazy in him to really do the part justice.

But that was a good thing.

Allman told me he'd met Morrison once. It was behind the Whiskey A Go Go in West Hollywood. The Doors singer was drinking a clear liquid out of a Heinz vinegar bottle. He handed the bottle to Allman, who took a sip.

He told me he awoke two weeks later, naked, in an apartment he didn't recognize. He borrowed some clothes from the closet and made it down to the street, back to his place.

I don't know how much of that story I believe, or how much Allman expected me to believe, and right now it seems impossible that we ever had that conversation. My friend who tried out to play Morrison is gone, and now Allman is too, so I can say what I want because there's no one left to contradict me.

Except when I told this story on my blog last week, a witness came forward to corroborate it. I didn't dream this encounter with Gregg Allman.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangel.com

Style on 06/11/2017