BENTONVILLE -- Beauty is its own brief. It doesn't need to explain itself. All it need do is sate some sensual appetite to earn its right to be here. It doesn't need to mean anything beyond what it makes apparent. It bends the light in a pleasing way? It stirs some inchoate longing? Let it be, child, let it be.

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art admits all kinds; patrons come in cargo shorts and overalls. There are school groups and scholars. If the museum's mission is to make the sublime accessible to the curious, it's doing a good job. The current exhibit of Dale Chihuly's glassworks promises to be popular, and there's something right about that.

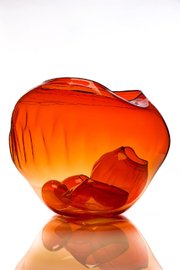

Chihuly makes pretty things, he blows -- well, these days it's more correct to say he produces -- colored glassworks. He works in collaboration with teams of artisans and the laws of physics, the terms of gravity and centrifugal force. There is an element of randomness in this work, what some might perceive as a lack of precision and predictability. But the means shouldn't matter, for real art eventually obliterates the artist, no matter how famous or fashionable the name.

There is a lot of Chihuly's work here now in the concurrent exhibits "Chihuly: In the Gallery" and "Chihuly: In the Forest" which run through Aug. 14 and Nov. 13, respectively. The former, inside the museum, consists of 300 pieces -- some of them new -- from 14 different series (Cylinders, Baskets, Persians and Venetians, et al.) while the latter features 10 large-scale sculptural works along the museum's newly opened North Forest Trail.

It is a very different kind of exhibit from the Chihuly show at the Clinton Presidential Center in 2014 in that this represents a sort of abridged career retrospective, with works from different eras of Chihuly's career. Here one can see the piece that's central to the artist's origin story -- a tapestry of fabric and colored glass, the result of a class assignment to weave together unusual materials.

"One night I decided I would melt some glass between four bricks and I took a pipe -- not a blow pipe, just a regular house pipe -- and gathered up some glass at the end of it and blew a bubble," the 75-year-old Chihuly told me in 2014, "from that moment on, I wanted to be a glass blower."

At the time Chihuly, who was born in Tacoma, Wash., was an indifferent interior design student at the University of Washington. After he graduated he enrolled in the first glassworks program in the country at the University of Wisconsin. Later he continued his studies at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he established a glass program and taught for more than a decade.

In 1968, after receiving a Fulbright Fellowship, he apprenticed at the Venini glass factory in Venice. There he was exposed to the team approach to glass blowing called the "Italian method," which profoundly influenced his approach. This sort of collaboration became essential after a 1976 car wreck (which cost him an eye and his depth perception and left him with a dashing, piratical eye patch) and an injury suffered while body surfing in 1979 (which cost him some physical strength that's vital when you're handling glass objects up to 4 feet or more in length). While Chihuly can still blow glass, he generally prefers to leave the chore to his assistants. Instead, he makes sketches -- many of which are on display in Crystal Bridges' gallery -- and supervises teams which can involve up to 18 artisans. He says he is better able to envision and direct the piece this way, that he has a better point of view than the head glass blower.

In 1971, armed with a $2,000 grant from the Union of Independent Colleges of Art, Chihuly led a free glass-blowing workshop -- students provided their own camping equipment and food and contributed junk glass to be melted down and reused -- in the Cascade Range 50 miles north of Seattle. This workshop eventually grew into the internationally renowned Pilchuck Glass School.

Now he's a singular presence -- a brand -- one of the most famous, prolific and commercially successful producers of beauty in the world, an entrepreneur who employs hundreds of artists and craftsmen in factories and warehouses that produce thousands of pieces a year. Chihuly isn't just a maker of beautiful objects, he's also a canny business intelligence and unrepentant self-promoter who has played the big art game well. He has courted celebrity collectors including Bono and Hillary Clinton. His work has not only been shown at the Musee des Arts Decoratifs at the Louvre, but in Las Vegas' Bellagio Hotel.

And he has drawn the disdain of critics.

"The history of art is a history of ideas, not just of valuable property," San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker wrote in 2008. "Chihuly has no place in it."

This is a fair summation of critical attitudes toward Chihuly's work; writers who've attempted to write about his "art" (and there is a real debate among some as to whether his pieces are works of art or craft) have trouble finding anything to say about it other than it's big, colorful and pretty. Like restaurant reviewers contemplating fast food, they tend to treat it as a guilty pleasure. Depending on their penchant for viciousness, they tend to express either benign indifference or open hostility. Chihuly is often compared to Thomas Kinkade, the late "painter of light" whose greeting card-worthy bucolic landscapes and radiant village scenes sometimes seem more akin to Jeff Koons' parodies of kitsch than the thing itself.

So why do we perceive Koons' work as a savage satire of kitsch and Kinkade's as bait for maiden aunts?

Intent.

Koons claims to appropriate the banal for his own ends, to subvert through copying the familiar and trite. Whereas Kinkade was a conservative Christian who professed his paintings were messages of God's love.

And Chihuly seems to have little interest in what critics might make or not make of his work.

"I really try to ... make something that feels right in the room," he said in 2014. " The inspiration comes a lot from the architecture. But for the most part, I'm just trying to make something I think looks really beautiful."

THE EMPEROR OF ICE CREAM

They are beautiful, if a little uncanny. Chihuly's work is nonrepresentational but often suggestive of vegetation or sea life. His ornamental Venetian series, for example, looks like an attempt to re-create classical and art deco vessels with found bits of feathers and leaves.

In a gallery, encountering a gang of Chihuly pieces, such as the 500-plus piece, 24-by-24-foot installation Mille Fiori ("thousand flowers") that was the highlight of his 2014 show at the Clinton Presidential Center, can be overwhelming, as though you've been sucked beneath a Disney-fied sea.

And seeing Chihuly's work in a natural outdoors setting, one is bound to be struck by how otherworldly his glass reeds and other vaguely plant-like objects seem. Glass is an organic material, but it's one that naturally occurs only in extreme circumstances. It fits, and yet it doesn't. His Neodymium Reeds installation seems to transform the Ozark forest setting into a alien jungle. His Fiori Boat reads as a harvest of undersea flora from some fantastic fauna. Sol de Oro, created especially for this exhibit from 1,400 translucent and golden pieces, is a milky, Medusian orb hovering like a drone (or burning bush) just off the path. In Red Reeds, one might detect a hint of menace -- they lean together like the rifles of bivouac-ed soldiers or rise like stained punji stakes. Boathouse 7 Neon pushes back against its natural surroundings, introducing the outdoor exhibit with a whimsical allusion to the commercial world. (Chihuly has been working with neon since his days at RISD.)

Inside there's another site-specific work, Azure Icicle Chandelier, hanging in the museum's Early Twentieth-Century Gallery (apart from the "Chihuly: In the Gallery" exhibit). It's comprised of 775 spear-shaped pieces created in Chihuly's studio, then shipped to Crystal Bridges where it was assembled by his studio team.

More than any other instance in which I've encountered Chihuly's work, the gallery exhibit at Crystal Bridges provides context and allows for at least a sense of the artist's progress. It's not arranged chronologically, but the dates and the videos help, as do Chihuly's studies for glassworks, displayed on the gallery walls. Even if one is tempted to consign Chihuly to the ranks of the decorative, his bold colors and sometimes surprisingly interesting rhythms attest to an original sensibility. Some of the most arresting work displayed -- Chihuly's layered glass-on-glass paintings and his Rotolo spirals of clear and dark blue glass -- is some of his most recent.

People are more likely to use words like "dazzling" and "spectacular" when describing the show, and there isn't anything wrong with that. Chihuly is popular. And we are well within our rights to be suspicious of the popular, for it implies a kind of lowest common denominator appeal. It may be true that there's not much here but fireworks. You might not be inspired to get pie and coffee after taking in the Chihuly show; you might not find that much to talk about.

But even so, most of us would like to have a piece or two from this collection. I found myself drawn to Chihuly's cylinders, inspired by American Indian textiles, with their intricately filigreed pigments. There is a place in most of our worlds for the pretty and it's worth considering that, to be successful, even as well-endowed an institution as Crystal Bridges needs to get people into the galleries. If you must, think of Chihuly as the popular musical that supports a theater group's brave interpretations of Ibsen.

While it's likely unhealthy to subsist on it, there's nothing wrong with liking ice cream. Chihuly's work is evocative and provocative. It's not nearly as fragile as it looks.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 06/25/2017

Dale Chihuly

“Chihuly: In the Gallery,” through Aug. 14 and “Chihuly: In the Forest,” through Nov. 13

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 600 Museum Way, Bentonville

Admission: $20 for adults, includes both exhibits. After “In the Gallery” closes, the cost will be $10 for “Chihuly: In the Forest.” Free for museum members and those 18 and younger.

Hours: 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday, Saturday-Sunday; 11 a.m.-9 p.m. Wednesday-Friday

Information: crystalbridges.org or (479) 418-5700